|

If,

like us, you were touched by the 2012 film Big Miracle, you'll already

know something about this magnificent animal. You'll know that despite

our differences, millions of people care about whales no matter what

colour or where on the globe they are found. Politicians all around the

world know of this common bond and that whales stand for peace and

understanding. Yet whaling continues to threaten these gentle giants and

humans don't seem to be able to live

side by side. We seem to be happier killing

our neighbor just because he occupies land with mineral riches, or

because we don't agree with their beliefs. Enough on that I think. But

is it right to let our hostility to our fellow man and general greed

endanger other species? Not if the film Big Miracle means anything.

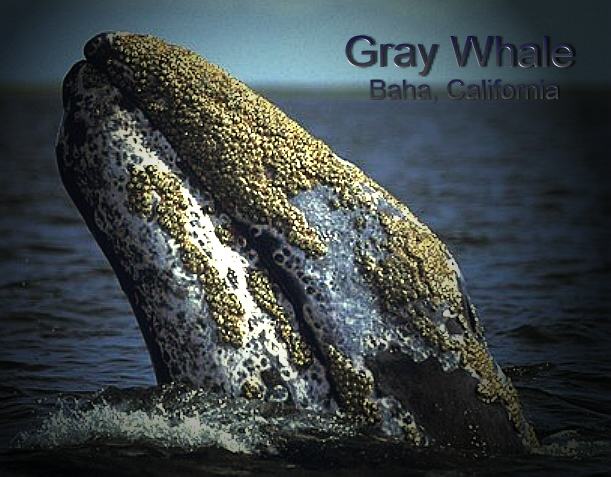

ESCHRICHTIUS

ROBUSTUS

The gray whale, (Eschrichtius robustus), is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. It reaches a length of about 16 m (52 ft), a weight of 36 tonnes (35 long tons; 40 short tons), and lives 50–70

years. The common name of the whale comes from the gray patches and white mottling on its dark

skin. Gray whales were once called devil fish because of their fighting behavior when

hunted. The gray whale is the sole living species in the genus Eschrichtius, which in turn is the sole living genus in the family Eschrichtiidae. This mammal descended from filter-feeding whales that developed at the beginning of the Oligocene, over 30 million years ago.

The gray whale is distributed in an eastern North Pacific (North

American) population and a critically endangered western North Pacific (Asian) population. North Atlantic populations were extirpated (perhaps by whaling) on the European coast before 500 AD and on the American coast around the late 17th to early 18th

centuries. However, on May 8, 2010, a sighting of a gray whale was confirmed off the coast of Israel in the Mediterranean

Sea, leading some scientists to think they might be repopulating old breeding grounds that have not been used for centuries.

DESCRIPTION

The gray whale is a dark slate-gray in color and covered by characteristic gray-white patterns, scars left by parasites which drop off in its cold feeding grounds. Individual whales are typically identified using photographs of their dorsal surface and matching the scars and patches associated with parasites that have fallen off the whale or are still attached.

Gray whales measure from 16 feet (4.9 m) in length for newborns to 43–50 feet (13–15 m) for adults (females tend to be slightly larger than adult males). Newborns are a darker gray to black in color. A mature gray whale can reach 40 tonnes (39 long tons; 44 short tons), with a typical range of 15 to 33 tonnes (15 to 32 long tons; 17 to 36 short

tons).

They have two blowholes on top of their head, which can create a distinctive V-shaped blow at the surface in calm wind conditions.

Notable features that distinguish the gray whale from other mysticetes include its baleen that is variously described as cream, off-white, or blond in color and is unusually short. Small depressions on the upper jaw each contain a lone stiff hair, but are only visible on close inspection. Its head's ventral surface lacks the numerous prominent furrows of the related rorquals, instead bearing two to five shallow furrows on the throat's underside. The gray whale also lacks a dorsal fin, instead bearing 6 to 12 dorsal crenulations ("knuckles"), which are raised bumps on the midline of its rear quarter, leading to the flukes. The tail itself is 10–12 feet (3.0–3.7 m) across and deeply notched at the center while its edges taper to a point.

POPULATIONS

Two Pacific Ocean populations are known to exist: one of not more than 130 individuals (according to the most recent population assessment in

2008) whose migratory route is presumed to be between the Sea of Okhotsk and southern Korea, and a larger one with a population between 20,000 and 22,000 individuals in the eastern Pacific travelling between the waters off Alaska and Baja

California Sur. The western population is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. No new reproductive females were recorded in 2010, resulting in a minimum of 26 reproductive females being observed since

1995. Even a very small number of additional annual female deaths will cause the subpopulation to

decline.

In 2007, S. Elizabeth Alter used a genetic approach to estimate prewhaling abundance based on samples from 42 California gray whales, and reported DNA variability at 10 genetic loci consistent with a population size of 76,000–118,000 individuals, three to five times larger than the average census size as measured through

2007. NOAA conducted a new populations study in 2010-2011; those data will be available by

2012. The ocean ecosystem has likely changed since the prewhaling era, making a return to prewhaling numbers infeasible; many marine ecologists argue that existing gray whale numbers in the eastern Pacific Ocean are approximately at the population's carrying

capacity.

The gray whale became extinct in the North Atlantic in the 18th

century. Radiocarbon dating of subfossil or fossil European (Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom) coastal remains confirms this, with whaling the possible

cause. Remains dating from the Roman epoch were found in the Mediterranean during excavation of the antique harbor of Lattara near Montpellier in 1997, raising the question of whether Atlantic gray whales migrated up and down the coast of Europe to calve in the

Mediterranean. Similarly, radiocarbon dating of American east coastal subfossil remains confirm gray whales existed at least through the 17th century. This population ranged at least from Southampton,

New York, to Jupiter Island,

Florida, the latest from

1675. In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the

settlers. A. B. Van Deinse points out that the "scrag whale", described by P. Dudley in 1725 as one of the species hunted by the early New England whalers, was almost certainly the gray

whale.

In mid-1980, there were three gray whale sightings in the eastern Beaufort Sea, placing them 585 kilometers (364 mi) further east than their known range at the

time. In May 2010, a gray whale was sighted off the Mediterranean shore of

Israel. It has been speculated that this whale crossed from the Pacific to the Atlantic via the Northwest Passage, since alternative routes through the Panama Canal or Cape Horn are not contiguous to the whale's established territory. There has been gradual melting and recession of Arctic sea ice with extreme loss in 2007 rendering the Northwest Passage "fully

navigable". The same whale was sighted again on June 8, 2010, off the coast of Barcelona,

Spain.

In January 2011, a gray whale that had been tagged in the western population was tracked as far east as the eastern population range off the coast of

British Columbia.

WHALING

North

Pacific

Humans and the killer whale (orca) are the adult gray whale's only predators. Aboriginal hunters, including those on Vancouver Island and the Makah in Washington, have hunted gray whales. The

Japanese began to catch gray whales beginning in the 1570s. At Kawajiri, Nagato, 169 gray whales were caught between 1698 and 1889. At Tsuro, Shikoku, 201 were taken between 1849 and

1896. Several hundred more were probably caught by American and European whalemen in the Sea of Okhotsk from the 1840s to the early 20th

century. Whalemen caught 44 with nets in Japan during the 1890s. The real damage was done between 1911 and 1933, when Japanese whalemen killed 1,449. By 1934, the western gray whale was near extinction. From 1891 to 1966, an estimated 1,800–2,000 gray whales were caught, with peak catches of 100–200 annually occurring in the

1910s.

Commercial whaling by Europeans of the species in the North Pacific began in the winter of 1845-46, when two United States ships, the Hibernia and the United States, under Captains Smith and Stevens, caught 32 in Magdalena Bay. More ships followed in the two following winters, after which gray whaling in the bay was nearly abandoned because "of the inferior quality and low price of the dark-colored gray whale oil, the low quality and quantity of whalebone from the gray, and the dangers of lagoon

whaling."

Gray whaling in Magdalena Bay was revived in the winter of 1855-56 by several vessels, mainly from San Francisco, including the ship Leonore, under Captain Charles Melville Scammon. This was the first of 11 winters from 1855 through 1865 known as the "bonanza period", during which gray whaling along the coast of Baja California reached its peak. Not only were the whales taken in Magdalena Bay, but also by ships anchored along the coast from San Diego south to Cabo San Lucas and from whaling stations from Crescent City in northern California south to San Ignacio Lagoon. During the same period, vessels targeting right and bowhead whales in the Gulf of Alaska, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Western Arctic would take the odd gray whale if neither of the more desirable two species were in

sight.

In December 1857, Charles Scammon, in the brig Boston, along with his schooner-tender Marin, entered Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Jack-Rabbit Spring Lagoon) or later known as Scammon's Lagoon (by 1860) and found one of the gray's last refuges. He caught 20

whales. He returned the following winter (1858–59) with the bark Ocean Bird and schooner tenders A.M. Simpson and Kate. In three months, he caught 47 cows, yielding 1,700 barrels (270 m3) of

oil. In the winter of 1859-60, Scammon, again in the bark Ocean Bird, along with several other vessels, performed a similar feat of daring by entering San Ignacio Lagoon to the south where he discovered the last breeding lagoon. Within only a couple of seasons, the lagoon was nearly devoid of

whales.

Between 1846 and 1874, an estimated 8,000 gray whales were killed by American and

European whalemen, with over half having been killed in the Magdalena Bay complex (Estero Santo Domingo, Magdalena Bay itself, and Almejas Bay) and by shore whalemen in California and Baja

California. This, for the most part, does not take into account the large number of calves injured or left to starve after their mothers had been killed in the breeding lagoons. Since whalemen primarily targeted these new mothers, several thousand deaths should probably be added to the

total. Shore whaling in California and Baja California continued after this period, until the early 20th century.

A second, shorter, and less intensive hunt occurred for gray whales in the eastern North Pacific. Only a few were caught from two whaling stations on the coast of California from 1919 to 1926, and a single station in Washington (1911–21) accounted for the capture of another. For the entire west coast of North America for the years 1919 to 1929, some 234 gray whales were caught. Only a dozen or so were taken by British Columbian stations, nearly all of them in 1953 at Coal

Harbour. A whaling station in Richmond, California, caught 311 gray whales for "scientific purposes" between 1964 and 1969. From 1961 to 1972, the Soviet Union caught 138 gray whales (they originally reported not having taken any). The only other significant catch was made in two seasons by the steam-schooner California off Malibu, California. In the winters of 1934-35 and 1935–36, the California anchored off Point Dume in Paradise Cove, processing gray whales. In 1936, gray whales became protected in the United

States.

As of 2001, the Californian gray whale population had grown to about 26,000. As of 2011, the population of western Pacific (seas near Korea, Japan, and Kamchatka) gray whales was an estimated

130.

PLASTIC

OCEAN POLLUTION - Baleen whales suffer from ingesting plastic in the

man-made soups that fester in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans.

This is so not just for the fact trash resembles their food, but because they gulp large amounts of water when feeding. In August 2000, a Bryde’s whale was stranded near Cairns, Australia. The stomach

of this whale was found to be tightly packed with six square meters of plastic rubbish, including supermarket bags, food packages, and fragments of trash bags. In April 2010, a gray whale that died after stranding itself on a west Seattle beach was found to have more than 20 plastic bags, small towels, surgical gloves, plastic pieces, duct tape, a pair of sweat pants, and a

golf ball, not to mention other garbage contained in its stomach. Plastic is not digestible, and once it finds its way into the intestines, accumulates and clogs the intestines. For some whales, the plastic does not kill the animal directly, but cause malnutrition and disease, which leads to unnecessary suffering until death.

Whales are not the only victims to our trash. It is estimated that over one million birds and 100,000 marine mammals die each year from plastic debris. In September 2009, photographs of

albatross chicks on Midway Atoll were brought to the public’s eye. These nesting chicks were fed bellies full of plastic by their parents who soar over vastly polluted oceans collecting what looks to them to be food. This diet of human trash kills tens of thousands of albatross chicks each year on Midway because of starvation, toxicity, and choking. We can all do our part by limiting our use of plastic products such as shopping bags, party balloons, straws, and plastic bottles. Be a frugal

shopper and recycle!

North Atlantic

The North Atlantic population may have been hunted to extinction in the 18th century. Circumstantial evidence indicates whaling could have contributed to this population's decline, as the increase in whaling activity in the 17th and 18th centuries coincided with the population's

disappearance. A. B. Van Deinse points out the "scrag whale", described by P. Dudley in 1725, as one target of early New England whalers, was almost certainly the gray

whale. In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony, a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the

settlers. Gray whales (Icelandic sandlægja) were described in Iceland in the early 17th

century.

Conservation

Gray whales have been granted protection from commercial hunting by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) since 1949, and are no longer hunted on a large scale.

Limited hunting of gray whales has continued since that time, however, primarily in the Chukotka region of northeastern Russia, where large numbers of gray whales spend the summer months. This hunt has been allowed under an "aboriginal/subsistence whaling" exception to the commercial-hunting ban. Antiwhaling groups have protested the hunt, saying the meat from the whales is not for traditional native consumption, but is used instead to feed animals in government-run fur farms; they cite annual catch numbers that rose dramatically during the 1940s, at the time when state-run fur farms were being established in the region. Although the Soviet government denied these charges as recently as 1987, in recent years the Russian government has acknowledged the practice. The Russian IWC delegation has said that the hunt is justified under the aboriginal/subsistence exemption, since the fur farms provide a necessary economic base for the region's native population.

Currently, the annual quota for the gray whale catch in the region is 140 per year. Pursuant to an agreement between the United States and

Russia, the Makah tribe of Washington claimed four whales from the IWC quota established at the 1997 meeting. With the exception of a single gray whale killed in 1999, the Makah people have been prevented from hunting by a series of legal challenges, culminating in a United States federal appeals court decision in December 2002 that required the National Marine Fisheries Service to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement. On September 8, 2007, five members of the Makah tribe shot a gray whale using high powered rifles in spite of the decision. The whale died within 12 hours, sinking while heading out to

sea.

As of 2008, the IUCN regards the gray whale as being of "Least Concern" from a conservation perspective. However, the specific subpopulation in the northwest Pacific is regarded as being "Critically

Endangered". The northwest Pacific population is also listed as endangered by the U.S. government’s National Marine Fisheries Service under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The IWC Bowhead, Right and Gray Whale subcommittee in 2011 reiterated the conservation risk to western gray whales is large because of the small size of the population and the potential anthropogenic

impacts.

In their breeding grounds in Baja California, Mexican law protects whales in their lagoons while still permitting whale

watching. Gray whales are protected under Canada's Species at Risk Act which obligates Canadian governments to prepare management plans for the whales and consider the interests of the whales when permitting

development.

Gray Whale migrations off of the Pacific Coast were observed, initially, by Marineland of the Pacific in Palos Verdes, California. The Gray Whale Census, an official Gray Whale migration census that has been recording data on the migration of the Pacific Gray Whale has been keeping track of the population of the Pacific Gray Whale since 1985. This census is the longest running census of the Pacific Gray Whale. Census keepers volunteer from December 1 through May, from sun up to sun down, seven days a week, keeping track of the amount of Gray Whales migrating through the area off of Los Angeles. Information from this census is listed through the American Cetacean Society of Los Angeles (ACSLA).

Threats

According to the Government of Canada's Management Plan for gray whales, threats to the eastern North Pacific population of gray whales

include:

-

Increased human activities in their breeding lagoons in Mexico

-

Climate change

-

Acute noise

-

The threat of toxic spills

-

Impacts from fossil

fuel exploration and extraction

-

Entanglement with

fishing gear

-

Boat collisions

-

Aboriginal whaling

Western gray whales are facing, the large-scale offshore oil and gas development programs near their summer feeding ground, as well as fatal net entrapments off Japan during migration, which pose significant threats to the future survival of the

population.

The substantial near-shore industrialization and shipping congestion throughout the migratory corridors of the western gray whale population represent potential threats by increasing the likelihood of exposure to ship strikes, chemical pollution, and general disturbance (Weller et al.

2002).

Offshore gas and oil development in the Okhotsk Sea within 20 km of the primary feeding ground off northeast Sakhalin Island is of particular concern. Activities related to oil and gas exploration, including geophysical seismic surveying, pipelaying and drilling operations, increased vessel traffic, and

oil

spills, all pose potential threats to western gray whales. Disturbance from underwater industrial noise may displace whales from critical feeding habitat. Physical habitat damage from drilling and dredging operations, combined with possible impacts of oil and chemical spills on benthic prey communities also warrants

concern.

FEEDING

The whale feeds mainly on benthic crustaceans, which it eats by turning on its side (usually the right, resulting in loss of eyesight in the right eye for many older animals) and scooping up sediments from the sea floor. It is classified as a baleen whale and has baleen, or whalebone, which acts like a sieve, to capture small sea animals, including amphipods taken in along with sand, water and other material. Mostly, the animal feeds in the northern waters during the summer; and opportunistically feeds during its migration, depending primarily on its extensive fat reserves. Calf gray whales drink 50 to 80 US gallons (190 to 300 l) of their mothers' 53% fat milk per

day.

The main feeding habitat of the western Pacific subpopulation is the shallow (5–15 m depth) shelf off northeastern Sakhalin Island, particularly off the southern portion of Piltun Lagoon, where the main prey species appear to be amphipods and

isopods. In some years, the whales have also used an offshore feeding ground in 30-35 m depth southeast of Chayvo Bay, where benthic amphipods and cumaceans are the main prey

species. Some gray whales have also been seen off western Kamchatka, but to date all whales photographed there are also known from the Piltun area.

MIGRATION

Each October, as the northern ice pushes southward, small groups of eastern gray whales in the eastern Pacific start a two- to three-month, 8,000–11,000-kilometer (5,000–6,800 mi) trip south. Beginning in the Bering and Chukchi seas and ending in the warm-water lagoons of Mexico's Baja peninsula and the southern Gulf of California, they travel along the west coast of

Canada, the United States and Mexico.

The western gray whale summers in the Okhotsk Sea, mainly off the northeastern coast of Sakhalin Island (Russian Federation). There are also occasional sightings off the eastern coast of Kamchatka (Russian Federation) and in other coastal waters of the northern Okhotsk

Sea,. Its migration routes and wintering grounds are poorly known, the only recent information being from occasional records on both the eastern and western coasts of Japan

and along the Chinese coast. The calving grounds are unknown but may be around Hainan Island, this being the southwestern end of the known

range.

Traveling night and day, the gray whale averages approximately 120 km (75 mi) per day at an average speed of 8 kilometers per hour (5 mph). This round trip of 16,000–22,000 km (9,900–14,000 mi) is believed to be the longest annual migration of any mammal. By mid-December to early January, the majority are usually found between Monterey and San Diego, often visible from shore. The whale watching industry provides ecotourists and marine mammal enthusiasts the opportunity to see groups of gray whales as they migrate.

By late December to early January, eastern grays begin to arrive in the calving lagoons of Baja. The three most popular lagoons are Laguna Ojo de Liebre (formerly known in English as Scammon's Lagoon after whaleman Charles Melville Scammon, who discovered the lagoons in the 1850s and hunted the

grays), San Ignacio, and Magdalena.

These first whales to arrive are usually pregnant mothers looking for the protection of the lagoons to bear their calves, along with single females seeking mates. By mid-February to mid-March, the bulk of the population has arrived in the lagoons, filling them with nursing, calving and mating gray whales.

Throughout February and March, the first to leave the lagoons are males and females without new calves. Pregnant females and nursing mothers with their newborns are the last to depart, leaving only when their calves are ready for the journey, which is usually from late March to mid-April. Often, a few mothers linger with their young calves well into May.

By late March or early April, the returning animals can be seen from Everett, Washington, to Puget Sound to Canada.

A population of about 200 gray whales stay along the eastern Pacific coast from Canada to California throughout the summer, not making the farther trip to

Alaskan waters. This summer resident group is known as the Pacific Coast feeding group.

CAPTIVITY

Because of their size and need to migrate, gray whales have rarely been held in captivity, and then only for brief periods of time.

In 1972, a three-month-old gray whale named Gigi (II) was captured for brief study by Dr. David W. Kenney, and then released near San

Diego.

In January 1997, the newborn baby whale J.J. was found helpless near the coast of Los Angeles, California, 4.2 m (14 ft) long and 800 kilograms (1,800 lb) in weight. Nursed back to health in SeaWorld San Diego, she was released into the Pacific Ocean on March 31, 1998, 9 m (30 ft) long and 8,500 kilograms (19,000 lb) in mass. She shed her radio transmitter packs three days later.

LINKS:

American Cetacean Society

Campaign Whale

Center for Whale Research

Cetacean Society International

Coast Watch Society

Gray Whales

with Winston

heatisonline.org (Ross

Gelbspan)

International Fund for Animal Welfare

International Whaling Commission

Interspecies Communication Inc.

National Marine Mammal Laboratory

Natural Resources Defense Council

Ocean Alliance

Ocean Defense International

Ocean Society

OnEarth (NRDC)

Project Seawolf

Save the Whales

Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

Solar Metro Online

blog

StopGlobalWarming.org

Society for Marine Mammalogy

Stripers Forever

U.S. Citizens Against Whaling

Whale Center of New England

Whaleman Foundation

WhaleNet

Whaling

Wild Coast

Jim

Cline Photo Workshops - Tours Baja whales

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC

- BALTIC

- BERING

- CARIBBEAN

- CORAL

- EAST

CHINA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC-

GULF

MEXICO - INDIAN

- MEDITERRANEAN

- NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN

GULF - SEA

JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON

- PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - UNEP

|