|

CAMERAS and PHOTOGRAPHY

|

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | NEWS | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT |

|

A camera is a device used to capture images, as still photographs or as sequences of moving images (movies or videos). The term as well as the modern-day camera evolved from the camera obscura, Latin for "dark chamber", an early mechanism for projecting images, in which an entire room functioned as a real-time imaging system. The camera obscura was first invented by the Iraqi scientist Alhazen and described in his Book of Optics (1011-1021). English scientists Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke later invented a portable camera obscura in 1665-1666.

Cameras may work with the light of the visible spectrum or with other portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. A camera generally consists of some kind of enclosed hollow, with an opening or aperture at one end for light to enter, and a recording or viewing surface for capturing the light at the other end. Most cameras have a lens positioned in front of the camera's opening to gather the incoming light and to focus the image, or part of the image, on the recording surface. The diameter of the aperture is often controlled by a diaphragm mechanism, but some cameras have a fixed-size aperture.

Large format lens camera

PHOTOGRAPHY

"Photography" is derived from the Greek words photos ("light") and graphein ("to draw") The word was first used by the scientist Sir John F.W. Herschel in 1839. It is a method of recording images by the action of light, or related radiation, on a sensitive material.

On a summer day in 1827, it took eight hours for Joseph Nicéphore Niépce to obtain the first fixed image. About the same time a fellow Frenchman, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre was experimenting to find a way to capture an image, but it would take another dozen years before he was able to reduce the exposure time to less than 30 minutes and keep the image from disappearing… ushering in the age of modern photography.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, inventor of the first practical process of photography, was born near Paris, France on November 18, 1789. A professional scene painter for the opera, Daguerre began experimenting with the effects of light upon translucent paintings in the 1820s. In 1829, he formed a partnership with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce to improve the process Niépce had developed to take the first permanent photograph in 1826-1827. Niépce died in 1833.

After several years of experimentation, Daguerre developed a more convenient and effective method of photography, naming it after himself -- the daguerreotype. In 1839, he and Niépce's son sold the rights for the daguerreotype to the French government and published a booklet describing the process.

The daguerreotype gained popularity quickly; by 1850, there were over seventy daguerreotype studios in New York City alone.

Pinhole Camera and Camera Obscura

Magic Lantern - Slide Projector

Flashlight Powder

Flashbulbs

Polaroid or Instant Photos

Disposable Camera

Frederick Charles Luther Wratten (1840-1926)

In 1878, Wratten invented the "noodling process" of silver-bromide gelatin emulsions before washing. In 1906, Wratten with the assistance of Dr. C.E. Kenneth Mees (E.C.K Mees) invented and produced the first panchromatic plates in England. Wratten is best known for the photographic filters that he invented and are still named after him - Wratten Filters. Eastman Kodak purchased his company in 1912.

Cameras: An Agfa Brownie, Polaroid Land Camera, and Yashica 35 mm SLR

Camera Exposure control

The size of the aperture and the brightness of the scene control the amount of light that enters the camera during a period of time, and the shutter controls the length of time that the light hits the recording surface. Equivalent exposures can be made with a larger aperture and a faster shutter speed or a corresponding smaller aperture and with the shutter speed slowed down.

Focus

Due to the optical properties of photographic lenses, only objects within a certain range of distances from the camera will be reproduced clearly. The process of adjusting this range is known as changing the camera's focus. There are various ways of focusing a camera accurately. The simplest cameras have fixed focus and use a small aperture and wide-angle lens to ensure that everything within a certain range of distance from the lens, usually around 3 metres (10 ft) to infinity, is in reasonable focus. Fixed focus cameras are usually inexpensive types, such as single-use cameras. The camera can also have a limited focusing range or scale-focus that is indicated on the camera body. The user will guess or calculate the distance to the subject and adjust the focus accordingly. On some cameras this is indicated by symbols (head-and-shoulders; two people standing upright; one tree; mountains).

Rangefinder cameras allow the distance to objects to be measured by means of a coupled parallax unit on top of the camera, allowing the focus to be set with accuracy. Single-lens reflex cameras allow the photographer to determine the focus and composition visually using the objective lens and a moving mirror to project the image onto a ground glass or plastic micro-prism screen. Twin-lens reflex cameras use an objective lens and a focusing lens unit (usually identical to the objective lens) in a parallel body for composition and focusing. View cameras use a ground glass screen which is removed and replaced by either a photographic plate or a reusable holder containing sheet film before exposure. Modern cameras often offer "auto-focus" systems to focus the camera automatically by a variety of methods.

19th century studio camera, with bellows for focusing

Image capture

Traditional cameras capture light onto photographic film or photographic plate. Video and digital cameras use electronics, usually a charge coupled device (CCD) or sometimes a CMOS sensor to capture images which can be transferred or stored in tape or computer memory inside the camera for later playback or processing.

Cameras that capture many images in sequence are known as movie cameras or as ciné cameras in Europe; those designed for single images are still cameras. However these categories overlap, as still cameras are often used to capture moving images in special effects work and modern digital cameras are often able to trivially switch between still and motion recording modes. A video camera is a category of movie camera which captures images electronically (either using analogue or digital technology).

Stereo camera can take photographs that appear "three-dimensional" by taking two different photographs which are combined to create the illusion of depth in the composite image. Stereo cameras for making 3D prints or slides have two lenses side by side. Stereo cameras for making lenticular prints have 3, 4, 5, or even more lenses. Some film cameras feature date imprinting devices that can print a date on the negative itself.

History

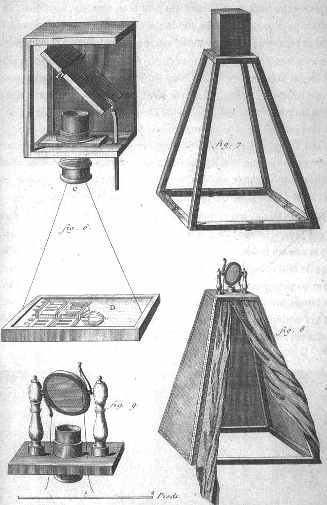

The forerunner to the camera was the camera obscura. The camera obscura is an instrument consisting of a darkened chamber or box, into which light is admitted through a double convex lens, forming an image of external objects on a surface of paper or glass, etc., placed at the focus of the lens. The camera obscura was first invented by the Iraqi scientist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) as described in his Book of Optics (1015-1021). English scientist Robert Boyle and his assistant Robert Hooke later developed a portable camera obscura in the 1660s.

The first camera that was small and portable enough to be practical for photography was built by Johann Zahn in 1685, though it would be almost 150 years before technology caught up to the point where this was possible. Early photographic cameras were essentially similar to Zahn's model, though usually with the addition of sliding boxes for focusing. Before each exposure, a sensitized plate would be inserted in front of the viewing screen to record the image. Jacques Daguerre's popular daguerreotype process utilized copper plates, while the calotype process invented by William Fox Talbot recorded images on paper.

The first permanent photograph was made in 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce using a sliding wooden box camera made by Charles and Vincent Chevalier in Paris. Niépce built on a discovery by Johann Heinrich Schultz (1724): a silver and chalk mixture darkens under exposure to light. However, while this was the birth of photography, the camera itself can be traced back much further. Before the invention of photography, there was no way to preserve the images produced by these cameras apart from manually tracing them.

The development of the collodion wet plate process by Frederick Scott Archer in 1850 cut exposure times dramatically, but required photographers to prepare and develop their glass plates on the spot, usually in a mobile darkroom. Despite their complexity, the wet-plate ambrotype and tintype processes were in widespread use in the latter half of the 19th century. Wet plate cameras were little different from previous designs, though there were some models, such as the sophisticated Dubroni of 1864, where the sensitizing and developing of the plates could be carried out inside the camera itself rather than in a separate darkroom. Other cameras were fitted with multiple lenses for making cartes de visite. It was during the wet plate era that the use of bellows for focusing became widespread.

The first color photograph was made by James Clerk Maxwell, with the help of Thomas Sutton, in 1861.

FILM IMPROVEMENTS

The first true photographs were exposed on metal that had been sensitized to accept an image. Daguerréotypes, named for their French inventor L.J.M. Daguerre in 1837, were metal sheets upon which a positive silver image was affixed.

The inventor of the first process which used a negative from which multiple prints were made was William Henry Fox Talbot, a contemporary of Daguerre.

Tintypes, patented in 1856 by Hamilton Smith, were another medium that heralded the birth of photography. A thin sheet of iron was used to provide a base for light-sensitive material, yielding a positive image.

Photography advanced considerably when sensitized materials could be coated on plate glass. The first glass negatives were wet plate. They had to be developed quickly before the emulsion dried. (In the field this meant carrying along a portable process had been invented and patented which freed the photographer from the necessity of developing each print immediately.)

In 1889, George Eastman, realizing the potential of the mass market, used a newly invented film with a base that was flexible, unbreakable, and could be rolled. Emulsions coated on a cellulose nitrate film base, such as Eastman's, made the mass-produced box camera a reality. Using box cameras, amateur photographers began to document everyday life in America. Eastman's first simple camera in 1888 was a wooden, light-tight box with a simple lens and shutter that was factory-filled with film. The photographer pushed a button to produce a negative. Once the film was used up, the photographer mailed the camera with the film still in it to the Kodak factory where the film was removed from the camera, processed, and printed. The camera was then reloaded with film and returned.

In the early 1940s, commercially viable color films (except Kodachrome, introduced in 1935) were brought to the market. These films used the modern technology of dye-coupled colors in which a chemical process connects the three dye layers together to create an apparent color image. This system is still used for color.

Camera obscura

Photographic Films

Black and white film is long lasting and more permanent than color film. The first flexible films, dating to 1889, were made of cellulose nitrate, which is chemically similar to guncotton. A nitrate-based film will deteriorate over time, releasing oxidants and acidic gasses. It is also highly flammable. Special storage for this film is required. It is highly explosive and should be kept at low temperatures, in sealed bags, in fireproof vaults.

Nitrate film is historically important because it allowed for the development of roll films. The first flexible movie films measured 35-mm wide and came in long rolls on a spool. In the mid-1920s, using this technology, 35-mm roll film was developed for the camera. By the late 1920s, medium-format roll film was created. It measured six centimeters wide and had a paper backing making it easy to handle in daylight. This led to the development of the twin-lens-reflex camera in 1929. Nitrate film was produced in sheets (4 x 5-inches) ending the need for fragile glass plates.

Triacetate film came later and was more stable, flexible, and fireproof. Most films produced up to the 1970s were based on this technology. Since the 1960s, polyester polymers have been used for gelatin base films. The plastic film base is far more stable than cellulose and is not a fire hazard.

In the past decade, film has become far less grainy and is greatly reduced in contrast. New technology has produced film with T-grain emulsions. These films use light-sensitive silver halides (grains) that are T-shaped, thus rendering a much finer grain pattern. Films like this offer greater detail and higher resolution, meaning sharper images. The traditional rule that slower film produces finer grain is no longer true. The finer grained films are still slower, that is, the ISO rating is lower, but they are much less grainy and have much less contrast.

A recent development in black and white film is a process that uses color film technology to develop and print black and white films. It is easy to take a roll of this film to a one-hour processor to get back prints quickly. However, the film has a purple tint to it, as do the prints. Additionally, because of the color processing, the life of the film or prints is highly suspect.

Photographic Prints

Traditionally, linen rag papers were used as the base for making photographic prints. Prints on this fiber-base paper coated with a gelatin emulsion are quite stable when properly processed. Their stability is enhanced if the print is toned with either sepia (brown tone) or selenium (light, silvery tone).

Paper will dry out and crack under poor archival conditions. Loss of the image can also be due to high humidity, but the real enemy of paper is chemical residue left by photographic fixer. In addition, contaminants in the water used for processing and washing can cause damage. If a print is not fully washed to remove all traces of fixer, the result will be discoloration and image loss. Staining also can occur on improperly processed negatives. The accepted current standard for adequate washing to remove the fixer is a minimum of 30 minutes with a total change of water every five minutes. (Commercial chemical preparations may be added to the bath to speed up the process.) A recent innovation in papers is the resin-coated, or water-resistant, paper. The idea is to use normal linen fiber-base paper and coat it with a plastic (polyethylene) material, making the paper water-resistant. The emulsion is placed on a plastic covered base paper. The problem with resin-coated papers is that the image rides on the plastic coating, and is susceptible to loss. Because resin-coated paper is considered unstable.

Only fiber-base paper, specially processed to archival standards, is acceptable for archival purposes. Most of today's commercially made prints are on resin-coated paper. Whether the print is from the corner drug store or a professional laboratory, it is almost certain to be made on resin-coated paper. Drug store prints are machine processed prints and are not as durable because the chemicals have not been completely washed out as in fine art printing.

Another film medium that is not suitable for photographic permanence is color. Color film and prints are not stable because organic dyes are used to make the color image. The image will quite literally disappear from the film or paper base as the dyes deteriorate. Kodachrome, dating to the first third of the 20th century, appears most stable and examples exist that are half a century old. Color transparency films by Fuji of Japan are proving to be stable, but only age (not accelerated aging tests) will reveal the truth.

Most recently, new techniques, along with some old ones, are creating what is called permanent color prints. The old fashioned dye transfer process has been reintroduced by two small companies. New printing methods using computer-generated thermal dye prints, digital images, supposedly highly stable pigments, and other technology claim to offer permanency for color media. It remains to be seen whether these claims can be substantiated. Other printing methods such as dye sublimation (a process for making paper prints that is created on a computer as a digital image), color Xerox, color laser, ink jet color, and other computer printers are so new that there is no data on how long these media will survive.

LINKS and REFERENCE

CAMERA MANUFACTURERS

Some notable camera manufacturers as of 2007:

1. European brands 2. Japanese brands 3. Russian brands 4. US Brands

....... The World in Your Hands

SolarNavigator began life in 1990s as an attempt to prove that the world could be navigated on solar power alone in a SWATH boat. Since then the hull design has been refined to a SWASSH configuration - and electronics have developed to the stage where this vessel could be the first true fully autonomous Robot Ship - ideal for extended 365 day a year hydrographic surveying and other persistent ocean monitoring and surveillance.

|

|

This

website

is Copyright © 1999 & 2013 NJK. The bird |

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEBIRD | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS |