|

THE FASTNET YACHT RACE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

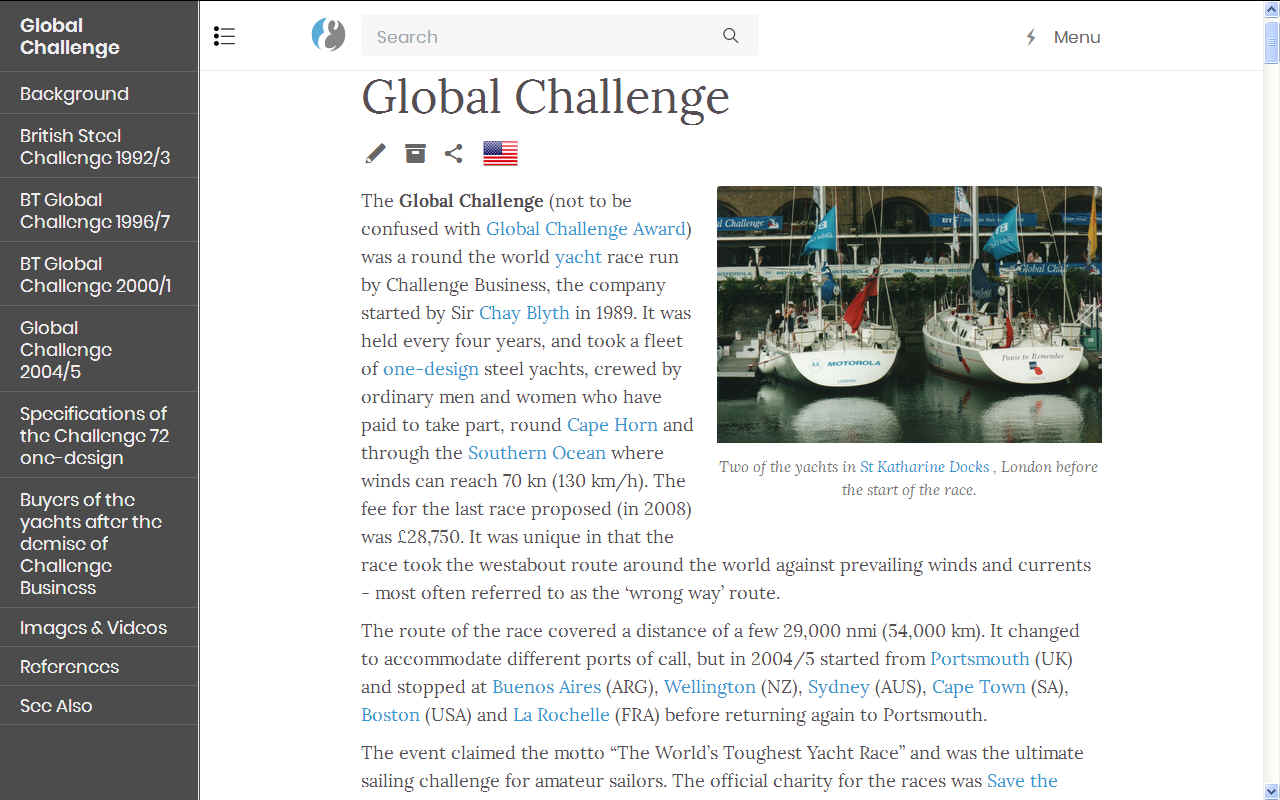

The Fastnet race is a yachting race in the United Kingdom. It is considered one of the classic offshore races. It happens every two years, and is a course of 608 miles. The course is unusual, as it begins off Cowes, travels to the Fastnet Rock off the southwest coast of Ireland, which the competitors round, and then back to Plymouth via the south side of the Isles of Scilly. The prize is known as the Fastnet Challenge Cup.

The Fastnet race route map

The Fastnet Race rightly has the reputation for being one of the toughest yacht races in the world. It can be the ultimate sailing challenge for those who want to stretch themselves to the limit. The 608 nautical mile course starts at Cowes then off westward to the Fastnet Rock off of southern Ireland before heading back to Plymouth.

The International Offshore Rule (IOR) was introduced in 1973, and the yachts and crews began taking sponsorships.

Storms during the 1979 race resulted in the deaths of 17 competitors. This led to a major overhaul of the rules and the equipment required for the competition.

The race drew further attention from outside the sport in 1985 when the maxi-yacht Drum capsized after her experimental keel sheared off. Pop star Simon Le Bon, co-owner and crew member of Drum, was trapped under the hull with five other crew members for twenty minutes, until being rescued by the Royal Navy. The Search and Rescue Diver was Petty Officer Air Crewman (POACMN) Larry "Scouse" Slater of 771 Naval Air Squadron who appeared on This Is Your Life on 9 April 1986.

Fastnet lighthouse

FASTNET 1979 AUGUST 14

Dozens of yachts have been lost and at least three people killed after a freak storm blew up in the Irish Sea during the Fastnet yacht race. Hundreds of competitors have been left stranded and there have been several reports of bodies floating in the sea.

Rescuers from both sides of the Irish sea are working around the clock to answer distress calls from many of the 303 yachts taking part in the ocean race. Naval helicopters from Culdrose have made dozens of sorties and have so far rescued about 100 people.

A Dutch warship and trawlers from France have also joined the rescue operation, which is the biggest ever launched in peace-time. A 20,000 mile (32,000 km) square area of sea is being searched for 150 yachts which are still missing. Damaged boats have been escorted into harbours from south-west tip of Ireland to the Isles of Scilly, some headed for Wales.

'Great Fury'

The Fastnet race is the last in a series of five races which make up the Admiral's Cup competition, the world championship of yacht racing. This year's race began from Cowes on the Isle of Wight on Saturday 11 August on a sunny day in calm waters. The course takes the yachts westwards across the Irish Sea, around Fastnet Rock off the coast of the Republic of Ireland and back to Plymouth. By yesterday lunch-time the weather conditions had deteriorated and some competitors talked of being hit by a "great fury" at sea.

Force seven winds whipped up mountainous waves and unpredictable tides caused chaos. One of the few boats to reach the finish line in Plymouth was Morning Cloud and her skipper, former prime minister Edward Heath. He said: "It's an experience that I do not think anybody would want to go through again willingly. "It was a raging sea with enormous waves and one of them picked us up and laid us on our side."

Owen Parker was the tactician and crew boss on one of the race favourites, Morning Cloud, the yacht owned and skippered by former British Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath. Owen sailed with Sir Edward for 12 years and was the man trusted to take the helm when the hurricane-force winds overtook the race fleet.

Edward Heath and Morning Cloud

Safety Issues

Questions about safety will now inevitably be raised and the future of the Fastnet race, organised by the Royal Ocean Racing Club, could be in jeopardy. Many of the smaller yachts taking part in the competition were not equipped with a radio and were therefore not able to report their positions. There have also been reports that some of the life-rafts broke up and safety harnesses snapped.

The Conservative government minister responsible for safety at sea, John Nott said: "It is a tragedy as many people have lost their lives. "But man is going to go on pitting himself against the elements and ocean racing will carry on. "There are always lessons to be learnt from every tragedy but I would not like people to feel that as a result of this disaster that the Fastnet race will not continue."

The final number of dead was 15 - six lives were lost because safety harnesses broke, the others drowned or died of hypothermia. Following the disaster the Royal Ocean Racing Club, which had organised the event, was heavily criticised but an official report into the disaster in December of that year cleared it of blame.

However, new special regulations were introduced which limited the number of yachts competing in the Fastnet race to 300. It became mandatory for all yachts to be equipped with a VHF radio and qualifications for competing were also brought in.

In 1983 restrictions on electronic navigational aids were also lifted. The race is still considered a supreme challenge for racing yachtsmen or women in British waters.

The winner of the 1979 race was Kiaola.

Matthew Sheahan

'Beyond fear'

Matthew Sheahan was only 17 when he entered the 1979 Fastnet race on his father's yacht, Grimalkin. The 608-mile (978 km) course started in near perfect conditions, but for the crew of Grimalkin it ended in tragedy as they battled to survive one of the worst storms to hit an ocean yacht race.

The first line of defence when conditions start to get tough is to reduce sail. We all did that, everybody in the fleet did that. There's nothing unusual in reefing down, or even reefing down until you've only got one tiny scrap of sail up. But what is unusual is to get to the point where you need to remove all the sails and sail under what we call "bare poles".

Cartwheel

As an indication of just how strong the conditions were, we were still sailing along at speeds we would have trouble getting to under full sail in decent conditions. As it got worse through the night we started to be knocked down. During the early hours of the morning we were capsized again and again.

When a yacht capsizes it's pretty dramatic. Each time we were thrown out of the boat. Sometimes it would just be rolled over onto its side and catapult the crew into the water. Other times it would roll completely over and come up the other way. Worse still was when it was "pitch-poled", when the boat actually does a cartwheel. The bow ploughs into the wave in front and the back gets lifted up by another wave.

Thunderous roar

And quite often the next thing would be popping out on the surface and being towed along by your safety harness behind the boat that was careering down the face of the wave. And bear in mind these waves were the size of buildings. This happened time and again throughout the night - it was utterly exhausting.

After first light we had one that was particularly bad. I was down below with my father trying to sort out some of the mess and decide on what we were going to be doing next. I heard this thunderous roar, a bit like I imagine an avalanche would sound. I glanced up through the window and saw this absolutely monstrous wave that was breaking and rolling down like a huge bit of Hawaiian surf.

Pinned down

Within seconds it had hit and we rolled over. The boat eventually came up the right way but my father had been concussed by some of the debris that was down below and wasn't in a good state. We got back on deck to check that everyone was OK and we got hit by another wave which rolled the boat over again. Except this time the boat didn't come up.

Fortunately for me, I'd been thrown clear of the boat, but only just - I was still attached on my harness. I was being pinned down by the deck, because my harness line wasn't quite long enough to get my head totally above water.

As I tried to get my life jacket and harness undone to allow my head above the water - which must have been maybe a couple of minutes later - the boat started to right itself. It then flicked around very quickly and because I hadn't undone my harness fully it launched me back into the cockpit. The boat had been dismasted, there were some crew lying in the cockpit, others hanging on outside the boat.

All of them had been trapped under the boat. One of crew had realised my father was in a very bad way and needed to get out from under the boat, and he had cut my father's safety harness to free him. As I stood up and looked upwind I could see a body face down in the water. We were drifting away from it. There was absolutely no question in my mind it was my father. The worst thing was that he was upwind of the boat and the boat was drifting downwind. Had it been the other way round we could have got the life raft or something to go downwind and help pick him up. But upwind in those conditions: impossible.

Life raft terror

After the final knock-down three of us decided it was right to get in the life raft. We couldn't move the other two, both of whom were unconscious and buried under broken spars and rigging and ropes. We decided it was better to get help and getting help meant getting into the life raft. But the life raft was the most terrifying part of the whole thing. It's like being in a toddler's paddling pool and being thrown into serious, serious weather. This inflatable raft was spun down the face of the waves and every now and then we thought it was going to flip over as a breaking wave either crashed over the top or forced up from underneath.

It was absolutely terrifying. We spent several hours in there until a helicopter plucked us out of the water. We then informed the rescue services immediately there were other people on the boat. There's not many days that go by that I don't think at least of my father and very often about the race. Sometimes events are so big and get so out of control as to make you feel miniscule. Something deep within you realises that there's absolutely nothing you can do about it. You almost go beyond a state of fear. The whole thing was completely and utterly overwhelming.

Fastnet Race 1979 - Grimalkin 30' yacht

Fastnet 2005

The 2005 race was sponsored by Rolex and is organised by the Royal Ocean Racing Club with the Royal Yacht Squadron and the Royal Western Yacht Club, Plymouth. The next race will start in August 2007.

Winners

Fastnet yachts racing

Antonio Elias Rodriguez, Winner 1994, Club de Yates de Acapulco, Mexico Boat: Olé, SC 70 All boats were catamarans apart from Charal-Sport-Elec-Geronimo || which was a trimaran. From 2004-2005 Steve Fossett held the record for the circumnavigation: 58 days 9 hours 32 minutes 45 seconds. As he did not pay the fee to qualify for the Jules Verne Trophy || he wasn't awarded the prize || but his record was acknowledged by the World Sailing Speed Record Council.

White Ocean Racing are seeking sponsorship for the remaining 2007 season for this Open 60 racing yacht and Steve White

LINKS and REFERENCE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2019. All rights reserved. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity.

|