|

BOUDICA QUEEN OF THE ICENI

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | BOOKS | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | NEWS | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Romans bit off a bit more than they cared to chew when they raped Boudica's daughters - the final straw. In every folk hero story, there is always one distinct action out of many wrongs, which finally proves too much for the victims.

Boudica

statue London What do we really know of this great British Queen of ancient Britain? She was married to Prasutagus, and with him she ruled over the Iceni - the tribe occupying East Anglia - but under Roman authority. Like many other rulers in Britain at this time, Boudicca witnessed the suffering caused to her people by the heavy taxes, conscription and other indignities generated by the Roman Emperor Nero. The final outrage came when her husband Prasutagus died, and the Romans plundered her chief tribesmen and brutally annexed her dominions. This was too much for the Queen and she determined to take on Nero and his Legions. In this she was not alone, for tradition tells that all of south east Britain came to her side, ready to die for the Queen who was fierce enough to take on the Roman Empire. It's noteworthy that tribes which remained loyal to the Romans, (like the Catuvellauni) were not spared Boudicca's wrath. Boudicca's opportunity came when the Roman Governor General Seutonius Paulinus and his troops were stationed in Anglesey and North Wales. By the time Paulinus got back, the Roman municipalities of St Albans and Colchester had been burned to the ground by the Britons. Boudicca's warriors were more than a little intimidating. They virtually routed the Ninth Legion that had been marching from Lincoln to help Paulinus, and without additional support from Rome there was little he could do against the determination of these people. Eventually they marched on London and it was here at last that Paulinus faced Boudicca and her army of Britons in the field. We don't know where, (possibly the Midlands) but we do know that a desperate battle was fought, and although the Romans were the victors, they regained the province at great price. Many thousands of Britons fell in battle and those who lived were hunted down by Roman soldiers. But it would seem that Boudicca's actions had shocked the Roman world into adopting policies that were a little kinder. Some historians believe that the relative lack of Romano-British remains in Norfolk is testimony to the severity with which the Roman Empire crushed Boudicca and the Iceni peoples. Finally, faced with defeat, the proud warrior Queen took her own life, by drinking from a poisoned chalice. This much is well known; the challenge is to separate fact from the many legends. For instance, is she really buried under Platform 10 at London's King's Cross Station? We'll probably never know, because for centuries people have been claiming their own local sites as her final resting place.

Boudica's of the World

Robin Hood is often considered the archetypal outlaw hero. As a result, many cultural heroes are referred to as the Robin Hoods of their respective countries.

The page links below are about Robin Hood-like characters from different countries. These heroes and villains can be real, legendary and completely fictional. It should also be noted that these legends are in no way inferior or subordinate to the Robin Hood legend. Some of these tales predate Robin's adventures. Boudica is real history and a message to tyrants the world over, which for some reason tyrants always seem to ignore - until it's to late.

Boudica's name

Until the late 20th century, Boudica was known as Boadicea, which is probably derived from a mistranscription when a manuscript of Tacitus was copied in the Middle Ages. Her name takes many forms in various manuscripts, but was almost certainly originally Boudicca or Boudica, derived from the Celtic word *bouda, victory (cf. Irish bua, Buaidheach, Welsh buddug). The name is attested in inscriptions as "Boudica" in Lusitania, "Boudiga" in Bordeaux and "Bodicca" in Britain.

Based on later development of Welsh and Irish, Kenneth Jackson concludes that the correct spelling of the name is Boudica, pronounced /bəʊˈdiːka:/, although it is mispronounced by many as /ˈbuːdɪkə/.

Background

Tacitus and Dio agree that Boudica was of royal descent. Dio says that she was "possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women", that she was tall, had long red hair down to her hips, a harsh voice and a piercing glare, and habitually wore a large golden necklace (perhaps a torc), a many-coloured tunic and a thick cloak fastened by a brooch.

Her husband, Prasutagus, was the king of Iceni, who inhabited roughly what is now Norfolk. They were initially not part of the territory under direct Roman control, having voluntarily allied themselves to Rome following Claudius's conquest of 43. They were jealous of their independence, and had revolted in 47 when the then-governor, Publius Ostorius Scapula, threatened to disarm them. Prasutagus lived a long life of conspicuous wealth, and, hoping to preserve his line, made the Roman emperor co-heir to his kingdom along with his two daughters.

It was normal Roman practice to allow allied kingdoms their independence only for the lifetime of their client king, who would agree to leave his kingdom to Rome in his will: the provinces of Bithynia and Galatia, for example, were incorporated into the Empire in just this way. Roman law also allowed inheritance only through the male line. So when Prasutagus died his attempts to preserve his line were ignored and his kingdom was annexed as if it had been conquered. Lands and property were confiscated and nobles treated like slaves. According to Tacitus, Boudica was flogged and her daughters raped. Dio Cassius says that Roman financiers, including Seneca the Younger, chose this point to call in their loans. Tacitus does not mention this, but does single out the procurator, Catus Decianus, for criticism for his "avarice". Prasutagus, it seems, had lived well on borrowed Roman money, and on his death his subjects had become liable for the debt.

statue of Emperor Claudius

Boudica's uprising

In 60 or 61, while the current governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was leading a campaign against the island of Anglesey in north Wales, which was a refuge for British rebels and a stronghold of the druids, the Iceni conspired with their neighbours the Trinovantes, amongst others, to revolt. Boudica was chosen as their leader. They drew inspiration from the example of Arminius, the prince of the Cherusci who had driven the Romans out of Germany in AD 9, and their own ancestors who had driven Julius Caesar from Britain. Dio says that at the outset Boudica employed a form of divination, releasing a hare from the folds of her dress and interpreting the direction it ran, and invoked Andraste, a British goddess of victory. It is perhaps significant that Boudica's own name means "victory".

The rebels' first target was Camulodunum (Colchester), the former Trinovantian capital and now a Roman colonia. The Roman veterans who had been settled there mistreated the locals, and a temple to the former emperor Claudius had been erected there at local expense, making the city a focus for resentment. Its inhabitants sought reinforcements from the procurator, Catus Decianus, but he sent only two hundred auxiliary troops. Boudica's army fell on the poorly defended city and destroyed it, besieging the last defenders in the temple for two days before it fell. The future governor Quintus Petillius Cerialis, then commanding the Legio IX Hispana, attempted to relieve the city, but his forces were routed. His infantry was wiped out: only the commander and some of his cavalry escaped. Catus Decianus fled to Gaul.

When news of the rebellion reached him, Suetonius hurried along Watling Street through hostile territory to Londinium (London). Londinium was a relatively new town, founded after the conquest of 43, but had grown to be a thriving commercial centre with a population of travellers, traders, and probably Roman officials. Suetonius considered giving battle there, but considering his lack of numbers and chastened by Petillius's defeat, decided to sacrifice the city to save the province. Londinium was abandoned to the rebels, who burnt it down, slaughtering anyone who had not evacuated with Suetonius. Archaeology shows a thick layer of burnt debris covering coins and pottery dating before 60 within the bounds of the Roman city. Verulamium (St Albans) was next to be destroyed.

In the three cities destroyed, between seventy and eighty thousand people are said to have been killed. Tacitus says the Britons had no interest in taking or selling prisoners, only in slaughter by gibbet, fire or cross. Dio's account gives more prurient detail: that the noblest women were impaled on spikes and had their breasts cut off and sewn to their mouths, "to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behaviour" in sacred places, particularly the groves of Andraste.

Romans rally

Suetonius regrouped with the XIV Gemina, some vexillationes (detachments) of the XX Valeria Victrix, and any available auxiliaries. The prefect of Legio II Augusta, Poenius Postumus, ignored the call, but nonetheless the governor was able to call on almost ten thousand men. He took a stand at an unidentified location, probably in the West Midlands somewhere along Watling Street, in a defile with a wood behind him. But his men were heavily outnumbered. Dio says that, even if they were lined up one deep, they would not have extended the length of Boudica's line: by now the rebel forces numbered 230,000.

Boudica exhorted her troops from her chariot, her daughters beside her. The historian Tacitus gives her a short speech in which she presents herself not as an aristocrat avenging her lost wealth, but as an ordinary person, avenging her lost freedom, her battered body and the abused chastity of her daughters. Their cause was just, and the gods were on their side: the one legion that had dared to face them had been destroyed. She, a woman, was resolved to win or die; if the men wanted to live in slavery, that was their choice . However, the unmaneuverability of the British forces, combined with lack of open-field tactics to command these numbers, put them at a disadvantage to the Romans, who were skilled at open combat due to their superior equipment and discipline, and the narrowness of the field meant that Boudica could only put forth as many troops as the Romans could at a given time. First, the Romans stood their ground and used waves of javelins to kill thousands of Britons who were rushing toward the Roman lines. The Roman soldiers, who had now used up their javelins, were then able to engage Boudica's second wave in the open, which made the Roman phalanx potent and difficult to break. As the phalanx advanced in a wedge formation, the Britons attempted to flee, but were impeded by the presence of their own families, whom they had stationed in a ring of wagons at the edge of the battlefield, and were slaughtered (The German king Ariovistus is reported to have made the same mistake in Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars). Tacitus reports that "according to one report almost eighty thousand Britons fell" compared with only four hundred Romans. According to Tacitus, Boudica poisoned herself; Dio says she fell sick and died, and was given a lavish burial.

Postumus, on hearing of the Roman victory, fell on his sword. Catus Decianus, who had fled to Gaul, was replaced by Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus. Suetonius conducted punitive operations, but criticism by Classicianus led to an investigation headed by Nero's freedman Polyclitus. Suetonius was removed as governor, replaced by the more conciliatory Publius Petronius Turpilianus. The historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus tells us the crisis had almost persuaded Nero to abandon Britain.

Location of her defeat

The site of Boudica's final battle is unknown. According to London legend it was at Battle Bridge Road, at King's Cross, London, and that Boudica herself is buried under one of the platforms at King's Cross railway station. However, based on Tacitus's account, it is unlikely Suetonius returned to London. Most historians favour a site in the West Midlands. Kevin K. Carroll suggests a site close to High Cross in Leicestershire, on the junction of Watling Street and the Fosse Way, which would have allowed the Legio II Augusta, based at Exeter, to rendezvous with the rest of Suetonius's forces. Manduessedum (Mancetter), near the modern day town of Atherstone in Warwickshire, has also been suggested.

REFERENCES and LINKS

MARITIME HISTORY

GENERAL HISTORY

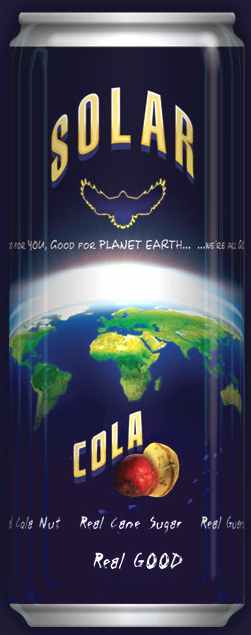

New energy drinks for performers .. Thirst for Life

330ml Earth can - the World in Your Hands

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2012 Electrick Publications. The bird logos and name Solar Navigator are trademarks. The name '1824' is a trade mark of Solar Cola Ltd. All rights reserved. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEPLANET | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS | SOLARNAVIGATOR | UTOPIA |