|

WHITBREAD

HISTORY

The

Whitbread story begins in August 1720 with the birth of

Samuel Whitbread. He was apprenticed as a brewer

in 1736 and founded his first brewery six years

later. In

1750 Samuel Whitbread moved his brewing operations to

premises in Chiswell Street on the eastern rim of

Georgian London, establishing the first purpose-built

mass-production brewery in Britain. Samuel's family name

quickly became synonymous with the brewing industry he

came to lead. The company he founded, and the beer it

produced in ever-increasing quantities, entered the

national consciousness, laying the foundations for one

of Britain's most enduring business success stories.

The

end of the 20th century and the start of the 21st marked

a watershed in the company's history, as Whitbread sold

its breweries and then exited its pubs and bars

business. After several decades of diversification,

during which the beer and pubs giant branched out into

new markets (including brief yet lucrative flirtations

with wines, spirits and night clubs), Whitbread

re-focused its business on the growth areas of hotels,

restaurants and health and fitness clubs. The

reinvention of Whitbread as the UK's leading leisure

business naturally coincided with the end of the brewing

and pub-owning tradition which Samuel Whitbread had

begun over 250 years earlier.

HOW

DID WHITBREAD COME TO SPONSOR AN OCEAN RACE

When

deep-ocean sailors gather to down a few pints, the

conversation inevitably turns to tales of passages made,

races won, and colleagues lost. It was at just such a

gathering in 1971 that the discussion turned to thoughts

of staging the ultimate race around the world -- a trip

of nearly 27,000 miles. It would be a race that pushed

the endurance of the crews and boats to the outer limits

as they navigated sweltering Doldrums, freezing oceans

filled with icebergs, and gales that blew unabated for

weeks on end -- a race that would be considered the Mt.

Everest of ocean racing.

Such a race, if it could be arranged, would have no

equal in sports. No other competition would ask so much

of both man and equipment. No other event would put so

many competitors at such risk, for so long, so far from

help.

But who would sponsor it? Besides its inherent dangers,

such a race would require a worldwide support system.

Ports of call would have to be established, rules,

scoring systems, and boat specifications would have to

be determined. Sponsors would have to be convinced to

finance what would be an enormously expensive event.

Many in the sailing establishment believed that even to

try such a race was folly. At that time, fewer than ten

private yachts had rounded Cape Horn -- in one piece.

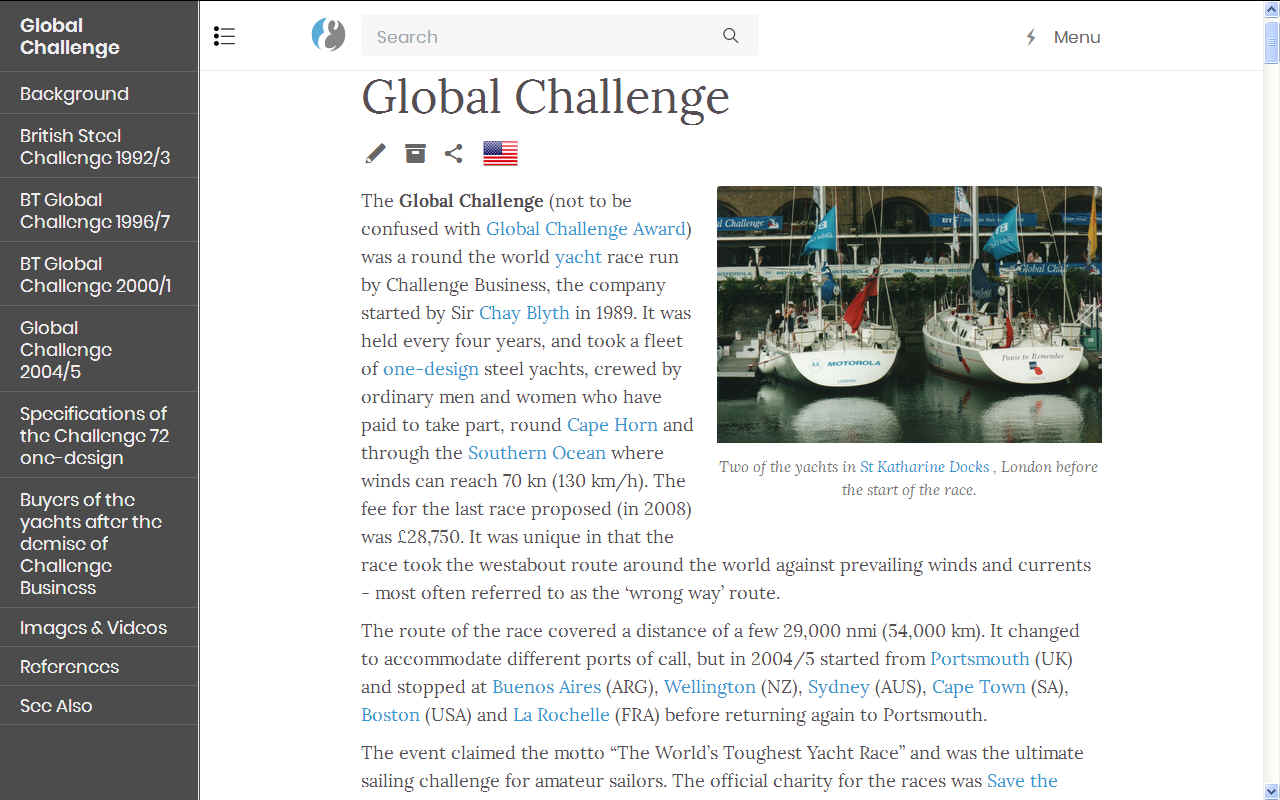

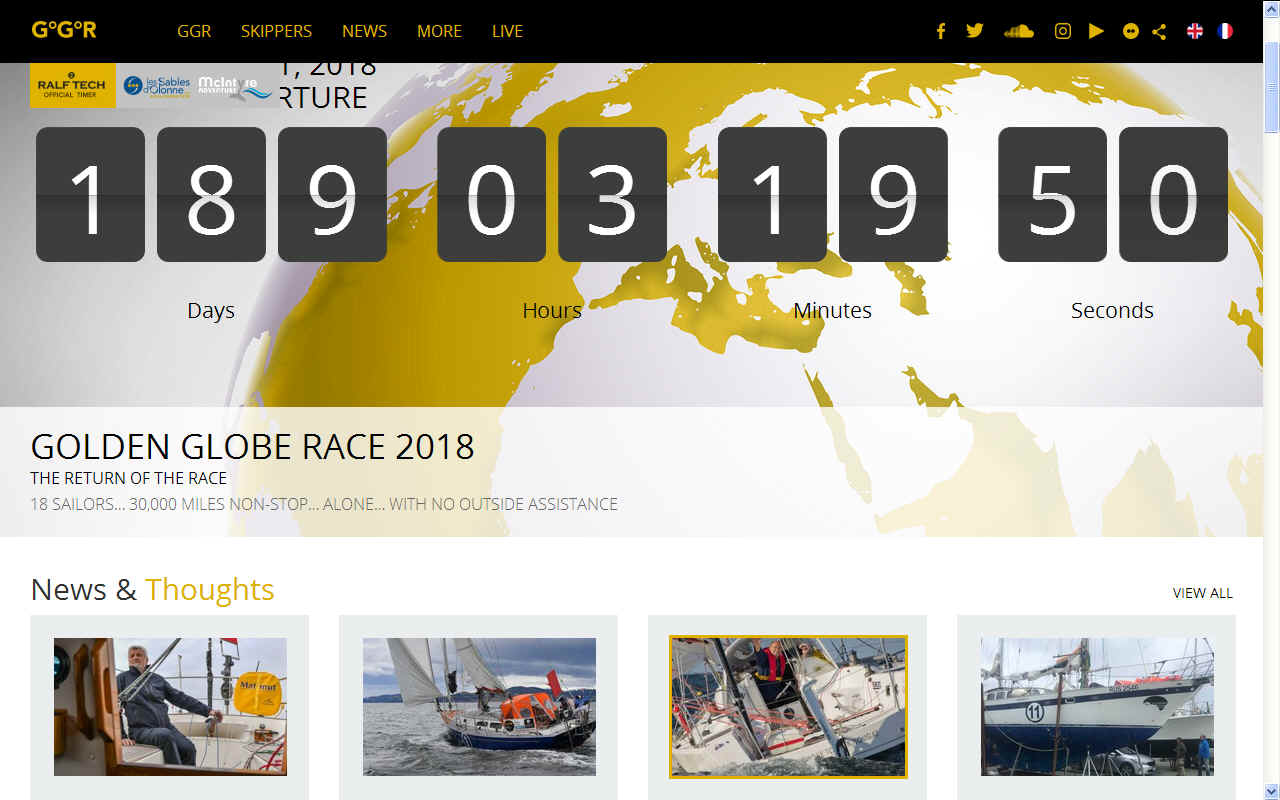

Moreover such a race already had been tried, and had

ended badly. In 1967, "The Sunday Times" of

London had put up money to sponsor what it called The

Golden Globe Race. Eight boats entered, but only one

finished. The others either gave up after near

catastrophic equipment failures, capsized, or sank. One

crewman became so despondent, he committed suicide.

These were not the sorts of events race sponsors were

eager to have associated with their names. However,

these brave racers had blazed a trail for 'round the

world sailors, providing an inspiration to others who

heard the call of a challenge.

In order to give the new race the credibility needed to

attract financing, a significant, high-profile backer

had to be found. Whomever it was, this backer had to

have a name and reputation so well-respected that it

alone would reassure the most nervous of the doubters.

This proved a hard sell. Sponsors of other ocean races

expressed little enthusiasm for the around-the-world

marathon envisioned by the organisers. The objections

especially revolved around the well-documented dangers

involved in sending such small boats into seas that have

swallowed galleons.

There, the plans might have died, had it not been for

the Royal Navy, which had open-ocean sailing plans of

its own. What private sector sponsors had viewed as

risks, the Royal Navy saw as assets. Seeing open-ocean

racing as a way to teach teamwork and build pride within

its ranks, the Royal Navy recently had taken delivery of

several Nicholson 55s. A global race seemed a good way

for the Royal Navy to become involved with the

ocean-racing community. In April 1972, while organisers

continued to search for private sponsors, the Royal

Naval Sailing Association announced that, even if no

private underwriter was found, it would support the race

the following year.

The RNSA's embrace proved to be the deciding factor. In

short order, contacts were made between the Royal Naval

Sailing Association and the corporate giant Whitbread

PLC. Almost as much a part of British history as the

Royal Navy, Whitbread's roots in British commerce

reached back to 1742. Over the centuries, the company

had grown to become one the world's most respected

purveyors of food, drink and leisure products --

employing over 70,000 people in 1997. In addition to its

sterling reputation, the Whitbread company also had the

real sterling -- the financial underpinnings -- to

instil faith in sponsors. With worldwide income

exceeding 2.7 billion pounds, Whitbread had the

financial wherewithal to underwrite such an ambitious

race.

The RNSA and Whitbread provided race organisers with the

administrative and financial critical mass they needed

to push the event from the drawing boards to the oceans.

Each brought unique resources to the table. Whitbread

lent its enormous prestige and underwriting muscle. The

Royal Naval Sailing Association provided the spacious

and secure Portsmouth Naval Base as a pre-race staging

area and starting line. For the race, the naval facility

seemed made to order. It comfortably could house the

large and expensive boats during the pre-race period,

while also providing military-base-type security. In

addition, the RNSA also could provide the worldwide

communications network to allow racers to communicate

from the farthest oceans to race headquarters in

Southampton.

But those were just the tangible benefits Whitbread PLC

and the RNSA provided. Each also delivered intangible

benefits by wrapping the new race in an aura of

tradition. No other navy in the world had a richer

seafaring history than the Royal Navy; it had for so

long ruled the world's seas, while sustaining Britain's

global colonial empire.

Whitbread PLC, on the other hand, represented British

mercantile history, reaching back to times when British

commerce stretched itself around the globe.

By mid-1973, the first Whitbread Round The World Race

was ready to begin. On 8 September, 17 boats, carrying

167 crew members hoisting sails in a blizzard of colour,

jockeyed to the starting line in Portsmouth Harbour.

With the shot of a simple starting pistol, the writing

of the first Whitbread saga began.

Cayard

Wins as Skipper for Team EF; Kostecki Sails for a

Competitor

America One Skipper and CEO Paul

Cayard has won the 1997-98 Whitbread Round the

World Race as skipper of EF Language, a

Swedish entry. The crew roster and shore team

included several members f the America One

team. (Click on the photo to see a larger image.)

The

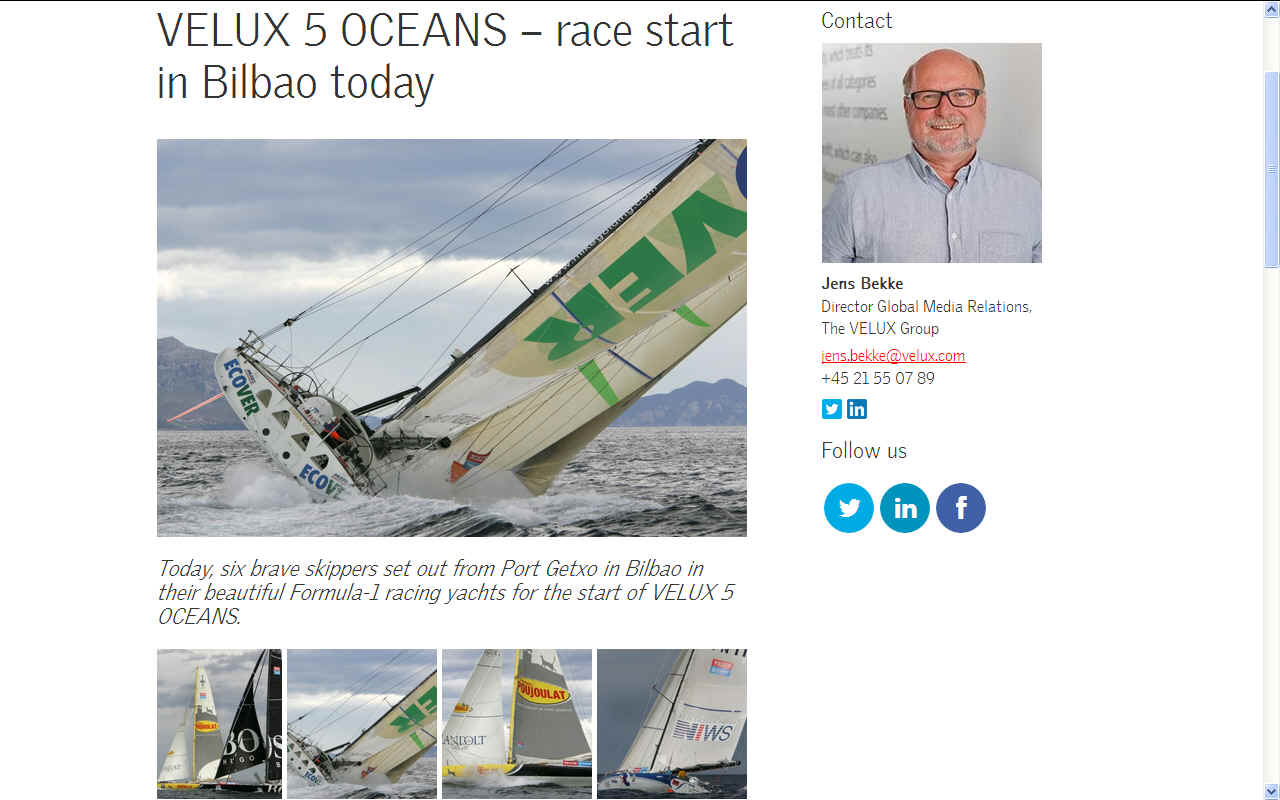

Whitbread Race is the one of the most challenging

sporting events ever conceived. A fleet of 60-foot

sailboats embark on a punishing circumnavigation of

the globe at breakneck speed. The first one home

claims the laurels of victory.

AmericaOne

tactician John Kostecki is sailing several of

the race legs aboard Chessie Racing, which is

based in Annapolis, Maryland.

The

Whitbread Race began at Cowes, England, on September

21, 1997, and finished in Southampton, England, on

May 24, 1998. The 32,000-mile ocean marathon

consists of nine legs and includes stops in Cape

Town, South Africa; Fremantle and Sydney, Australia;

Auckland, New Zealand; São Sebastião, Brazil; Fort

Lauderdale and Baltimore/Annapolis in the United

States; and La Rochelle, France

|

|

Skipper

Paul Cayard talks about the bonding that takes

place when sailors share the "ups" and

"downs" of long ocean voyages

(9/21/98)

|

|

|

Skipper

Paul Cayard discusses the differences between

racing in the Whitbread and the America's Cup.

(10/31/98)

|

1997

and 1993 Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race

The

Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race is now known

as the Volvo Ocean Race, and is the world's most

prestigious yacht race. Fremantle hosted the

stopover in 1993 and 1997/98 and was widely

regarded by the sailors as the most enjoyable and

relaxing host port of the race. Fremantle's

superb yachting facilities, its hospitality, the

Race organisation and perfect weather conditions

assured an unsurpassed stop over.

In

1997, Quokka Sports initiated internet-based

coverage of the Whitbread Round the World Race for

the Volvo Trophy. Their pioneering web site

brought minute-by-minute images of the race to the

world, creating a unique photographic record for

sailing enthusiasts.

Whitbread

Restaurant brands

Whitbread

PLC.

Julie

Weldon

Corporate PR Manager

Tel: 020 7806 5443

Fax: 020 7806 5458

julie.weldon@whitbread.com

Sports

David

Lloyd Leisure

Mark Webb

PR Manager

Tel: 01582 844257

Fax: 01582 888889

mark.webb@whitbread.com

Healthier

alternative tastes for adventure capitalists

Solar

Red | Solar

Crush | Solar

Cola | Solar

Spice | Solar

+

|