|

WORLD WATER SPEED RECORDS - WWSR

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The World Unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle. The current record of 511 km/h (317 mph) was achieved in 1978.

With an approximate fatality rate of 50%, the record is one of the sporting world's most hazardous competitions.

1910s

Beginning in 1908, Alexander Graham Bell and engineer Frederick W. "Casey" Baldwin began experimenting with powered watercraft. In 1919, with Baldwin piloting their HD-4 hydrofoil, a new world water speed record of 70.86 mph was set on Bras d'Or Lake in Nova Scotia.

1920s

During the 1920s powerboat racing was dominated by American businessman and racer Gar Wood, whose Miss America boats were capable of speeds approaching 160 kilometers per hour (100 mph). Increased public interest generated by the speeds achieved by Wood and others led to an official speed record being ratified in 1928. The first person to try a record attempt was Gar Wood’s brother George. On 4 September 1928 he drove Miss America VII to 149.40 km/h (92.83 mph) on the Detroit River. The next year Gar Wood took the same boat up a waterway Indian Creek, Miami and reached 149.86 km/h (93.12 mph).

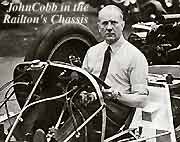

John Cobb - 1900-1952

1930s

Like the land speed record, the water record was destined to become a scrap for national honour between Britain and the USA. American success in setting records spurred Castrol Oil chairman Lord Wakefield to sponsor a project to bring the water record to Britain. Famed land speed record breaker and racing driver Sir Henry Segrave was hired to pilot a new boat called Miss England. Although the boat wasn’t capable of beating Gar Wood’s Miss America, the British team did gain experience that they put into an improved boat. Miss England II was powered by two Rolls-Royce aircraft engines and seemed capable of beating Wood’s record.

On July 13, 1930, Segrave drove Miss England II to a new record of 158.94 km/h (98.76 mph) average speed during two runs on Windermere, in Britain’s Lake District. Having set the record, Segrave set off on a third run to try to improve the record further. Unfortunately during the run, the boat struck an object in the water and capsized, with both Segrave and his co-driver receiving fatal injuries.

Following Segrave’s death, Miss England II was salvaged from the lake and repaired. Another racing driver, Kaye Don, was chosen as the new driver for 1931. However, during this time Gar Wood recaptured the record for the US at 164.41 km/h (102.16 mph). A month later on Lake Garda, Don fought back with 177.387 km/h (110.223 mph). In February 1932, Wood responded, nudging the mark up by 1.6 km/h (1 mph).

In response to the continued American challenge, the British team built a new boat, Miss England III. The design was an evolution of the predecessor, with a squared-off stern and twin propellers being the main improvements. Don took the new boat to Loch Lomond in Scotland, on July 18, 1932, improved the record first to 188.985 km/h (117.430 mph), and then to 192.816 km/h (119.810 mph) on a second run.

Miss England II driven by Kaye Don

Determined to have the last word over his great rival, Gar Wood built another new Miss America. Miss America X was 12 metres long, and was powered by four supercharged Packard aeroplane engines. On September 20, 1932, Wood drove his new monster-boat to 200.943 km/h (124.860 mph). It would prove to be the end of an era. Don declined to attempt any further records, and Miss England III became a museum piece. Wood also opted to scale-down his involvement in racing and returned to running his businesses. Somewhat ironically, both of the daredevil record-breakers would live to their 90s. Wood died in 1971, and Kaye Don in 1985.

Boat design changes

Wood’s last record would be one of the final records for a conventional, single-keel boat. In June 1937, Malcolm Campbell, the world-famous land speed record breaker, drove Bluebird K3 to a new record of 203.31 km/h (126.33 mph) at Lake Maggiore. Compared to the massive Miss America X, K3 was a much more compact craft. It was 5 metres shorter and had one engine to X's four. Despite his success, Campbell was unsatisfied by the relatively small increase in speed. He commissioned a new Bluebird to be built. K4 was a ‘three pointer’ hydroplane. Unlike conventional powerboats, which have a single keel, with an indent, or ‘step’, cut from the bottom to reduce drag, a hydroplane has a concave base with two floats fitted to the front, and a third point at the rear of the hull. When the boat increases in speed, most of the hull lifts out of the water and runs on the three contact points. The positive effect is a reduction in drag and an increase in power-to-weight ratio - the boat is lighter as it doesn’t need many engines to push it along. The downside is that the three-pointer is much less stable than the single keel boat. If the hydroplane’s angle of attack is upset at speed, the craft can somersault into the air, or nose-dive into the water.

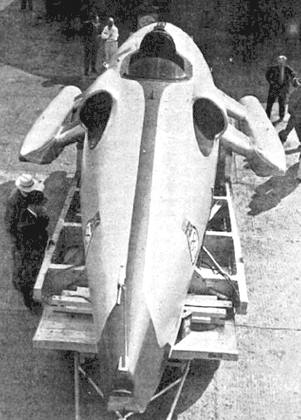

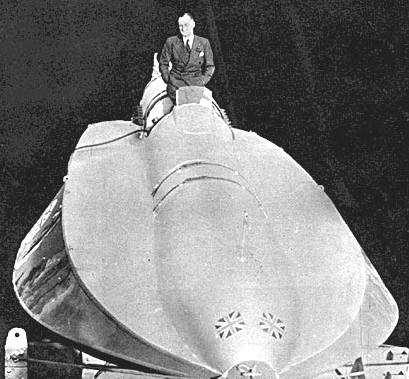

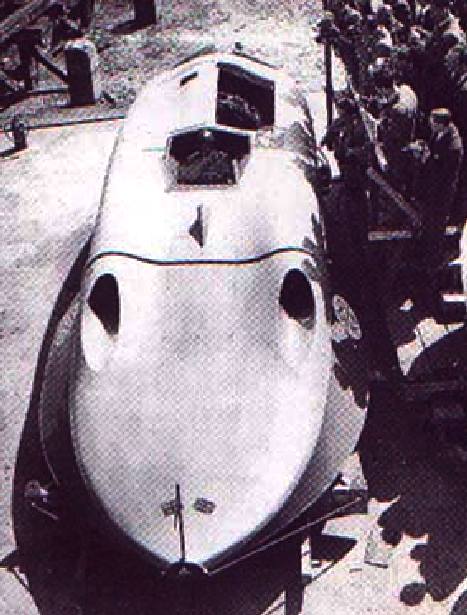

John Cobb's Crusader jet powered WSR boat

1940s

Campbell’s new boat was a success. In 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, he took it to Coniston Water and increased his record by 18 km/h (11 mph), to 228.11 km/h (141.74 mph). The return of peace in 1945 brought with it a new form of power for the record breaker – the jet engine. Campbell immediately renovated Bluebird K4 with a De Havilland Goblin jet engine. The result was a curious-looking craft, whose shoe-like profile led to it being nicknamed ‘The Coniston Slipper’. The experiment with jet-power was not a success and Campbell retired from record-attempts. He died in 1948.

1950s. Slo-Mo-Shun and Bluebird: Propriders to Turbojets

Early in the morning of June 26, 1950, a small red boat skipped across Lake Washington, near Seattle, and improved on Campbell’s record by 29 km/h (18 mph). The boat was called Slo-Mo-Shun-IV, and it was built by Seattle Chrysler dealer called Stanley Sayres. The piston-engined boat was able to run at 160 mph because its hull was designed to lift the top of the propellers out of water when running at high speed. This phenomenon, called ‘prop riding’, further reduced drag.

In 1952, Sayres drove Slo-Mo-Shun to 287.25 km/h (178.49 mph) - a further 29 km/h (18 mph) increase. The renewed American success persuaded Malcolm Campbell’s son Donald, who had already driven Bluebird K4 to within sight of his father’s record, to make a push for the record. However, the K4 was completely out-classed and Campbell could not run at the speeds of the Seattle-built boat. In 1951 K4 was written-off when it hit a submerged object on Coniston.

[Left] Sir Malcolm Campbell and the K3 original Rolls Royce Merlin engined superstructure, and [Right] the re-bodied jet engined "slipper" Bluebird K4.

At this time, yet another land speed driver entered the fray. Englishman John Cobb, was hoping to beat 320 km/h (200 mph) in his jet-powered, all-aluminium built Crusader. A radical design, the Crusader reversed the ‘three-pointer’ design, placing the floats at the rear of the hull. On September 29, 1952, Cobb tried for a 320 km/h (200 mph) record on Loch Ness. Travelling at an estimated speed of 386 km/h (240 mph), Crusader's front plane collapsed and the craft instantly disintegrated. Cobb was rescued from the water but died of shock soon afterward.

Two years later, on October 8, 1954, another man would die trying for the record. Italian textile magnates Mario Verga and Francesco Vitetta, responding to a prize offer of 5 million lire from the Italian Motorboat Federation to any Italian who break the world record, built a sleek piston-engined hydroplane to claim the record. Named Laura, after Verga’s daughter, the boat was fast but unstable. Traveling across Lake Iseo at close to 306 km/h (190 mph), Verga lost control of Laura, and was thrown out into the water when the boat somersaulted. Like Cobb, he died of shock.

Following Cobbs death, Donald Campbell started working on a new Bluebird - K7, a jet powered hydroplane. Learning the many lessons from Cobb’s ill-starred Crusader, K7 was designed as a classic 3 pointer with sponsons forward alongside the cockpit.

The 26ft long, 10ft wide, 5 ft high, 2.5 ton craft was designed by Ken and Lewis Norris in 1953-54 and was completed in early 1955. It was powered by a Metropolitan-Vickers Beryl turbojet of 3500lbs thrust. K7 was of all metal construction and proved to have extremely high rigidity.

Campbell and K7 set a new record of 325.60 km/h (202.32 mph) on Ullswater in July 1955. Campbell and K7 went on to break the record a further six times over the next nine years in the USA and England (Lake Coniston), finally increasing it to 444.71 km/h (276.33 mph) at Lake Dumbleyung in Western Australia in 1964. Donald Campbell thus became the most prolific water speed record breaker of all time.

Donald Campbell in Bluebird K7

1967

Donald Campbell arrived back at Coniston Water, scene of previous triumphs, in November 1966. Bluebird K7 had been re-engined with a Bristol-Siddeley Orpheus jet rated at 4500lbs thrust. His stated aim was to bump the record out of reach of the Americans, and push it beyond 300mph (480kph) The new attempt suffered many setbacks both mechanical, and weather related, and time by the end of 1966, Campbell existing 276mph record was still not broken. On the morning of January 4, 1967, he was a man under pressure, but the day dawned still, and conditions seemed perfect.

Bluebird K7 was over a decade old, and an American called Lee Taylor was threatening the record with a new boat, Hustler. The patriotic Campbell desperately wanted a Briton to be the first to break 480 km/h (300 mph). His first run across the lake was untroubled and fast. K7 averaged 475.2 km/h (297.6 mph). A new record seemed in sight. Campbell applied K7's water brake to slow the craft down from her peak speed of 315mph as she left the measured Kilo. The wake caused by the water brake was very large from traveling at such high speeds, so Campbell would normally refuel and wait, before starting the mandatory return leg, for the lake to settle again. This time, perhaps fearing that conditions would deteriorate if he waited, Campbell immediately turned around at the end of the lake and began his return run, to try and beat his own wash. Bluebird came back on her return even faster. At around 512 km/h (320 mph), just as she entered the measured Kilo, Bluebird met its wake from the first run. The boat began to lose stability, and finally, 100m before the end of the Kilo, its nose lifted at a 45 degree angle. The boat took off, somersaulted and then plunged nose-first into the lake, breaking up as she cart-wheeled across the surface. Campbell was killed instantly. Prolonged searches over the next two weeks located the wreck, but it was not until May 2001 that Campbell's body was finally located and recovered. Campbell was laid to rest in the churchyard at Coniston on the 12 September 2001

Lee Taylor, a Californian boat racer, had first tried for the record in April 1964. His boat Hustler was similar in design to Bluebird K7, being a jet hydroplane. During a test run on Lake Havasu Taylor was unable to shut down the jet and crashed into the lakeside at over 100mph. Hustler was wrecked and Taylor was severely injured. He spent the following years recuperating, and rebuilding his boat. On June 30, 1967 on Lake Guntersville, Taylor and Hustler tried for the record, but the wake of some spectator’s boats disturbed the water, forcing Taylor to slow down his second run, and he came up 3.2 km/h (2 mph) short. He tried again later the same day and succeeded in setting a new record of 459 km/h (286.875 mph).

Bluebird K7 crash 4 January 1967 - Click picture for video

1970s to the present

Until November 20, 1977, every official water speed record had been set by an American or Briton. That day Australian Ken Warby broke the Anglo-American domination when he piloted his Spirit of Australia to 464.5 km/h (290.313 mph) to beat Lee Taylor’s record. Warby, who had built the craft in his back yard, used the publicity to find sponsorship to pay for improvements to the Spirit. On October 8, 1978 Warby travelled to Blowering Dam, Australia, and broke both the 480 km/h (300 mph) and 500 km/h barriers with an average speed of 510 km/h (318.75 mph).

As of 2005, Warby’s record still stands, and there have only been two official attempts to break it.

Lee Taylor tried to get the record back in 1980. Inspired by the land speed record cars Blue Flame and Budweiser Rocket, Taylor built a rocket-powered boat, Discovery II. The 40-foot long craft was a reverse three-point design, similar to John Cobb’s Crusader, albeit of much greater length.

Originally Taylor tested the boat on Walker Lake in Nevada but his backers demanded a more accessible location, so Taylor switched to Lake Tahoe. An attempt was set for November 13, 1980, but when conditions on the lake proved unfavourable, Taylor decided against trying for the record. Not wanting to disappoint the assembled spectators and media, he decided to do a test run instead. At 432 km/h (270 mph) Discovery II hit a swell and one of the floats collapsed, sending the boat plunging into the water. Taylor’s body and his destroyed craft were never recovered.

In 1989, Craig Arfons, nephew of famed record breaker Art Arfons, tried for the record in his all-carbon-fibre Rain X Challenger, but died when the hydroplane somersaulted at 483 km/h (301.875 mph).

Despite the high fatality rate, the record is still coveted by boat enthusiasts and racers. Currently there are three major projects aiming for the record. The British Quicksilver [1], The American Challenge project [2], and spurred into action by the new challengers, Ken Warby has also built a new boat [3].

In 2001, Bluebird K7 was raised from Coniston Water by members of the Bluebird Project.

Anthony Hopkins plays Donald Campbell

RECORD HOLDERS

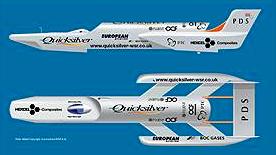

Quicksilver - early drawing

The Future

A British man is planning a new assault on the world water speed record. Nigel Macknight says that after an absence of 34 years, it is time the record was returned to Britain.

He

believes his boat Quicksilver can make him the fastest man on water, and

plans are underway for an attempt on the record at Consiston Water, in

the Lake District. "There

is unfinished business on Coniston," he says, with quiet

determination.

Campbell

legacy

He is referring to Donald Campbell, the last Briton to hold the water speed record. He died on the lake in 1967, attempting to take his boat Bluebird through the 300 mph (480 km/h) barrier. His body was recently recovered from the depths, and is now buried in a local churchyard.

Nigel

Macknight aims to succeed where Campbell failed. Construction of his

boat is now well underway, with water trials scheduled for next summer,

possibly in France or Switzerland. The attempt on the record is expected

to follow at Coniston, during the winter months.

Quicksilver is designed to reach 400 mph (640 km/h). But because the lake only provides a five-mile (8 km) run, it will be difficult to go beyond 325-330 mph (520-530 km/h).

Quicksilver - early model

Nigel Macknight, initiator of the Quicksilver project, is the man who'll be at the controls of the multi-million pound supereboat for the record bid. Nigel has been guided by his mentor, Ken Norris, following the same path Ken mapped out for Richard Noble and Thrust 2, which took the land speed record in 1981.

Originally from Corbridge in Northumberland, Nigel became a professional writer at the age of 21. His first article to appear in print was Speed Kings, an account of the record-breaking exploits of Sir Malcolm and Donald Campbell.

Dangers

Nigel Macknight's challenge will cost £3m. It's a huge sum, but he has already raised half, through sponsorship with more than 30 companies. About 100 individuals have volunteered their support, among them members of the Thrust team who captured the world land speed record.

Nigel

does not back away from the obvious question: isn't this incredibly

dangerous? Donald Campbell died when his boat took off and flipped over.

Others have been killed chasing the same record.

"The

risks are on a par with motor sports and mountaineering," says

Nigel, who is 46 and lives in Lincolnshire. "It is not entirely

safe, but it is an acceptable risk."

Quicksilver design concept

Speed: 400 mph Engine: Rolls-Royce Spey 101 turbofan Thrust: 11,030 lbs Construction: high tensile steel tubing, honeycomb panels

Nigel MacKnight

Simulations

He points to the improvements in technology since Campbell's day, and cites motor racing as an example. "It has altered out of all recognition," he argues.

"We

like to think there has been a similar evolution in our project."

Donald Campbell's boat Bluebird was never designed to travel at 300 mph.

Quicksilver

has been through an extensive period of development, including tests of

models in a wind tunnel and a water tank, and inevitably in this day and

age, computer simulations.

Borderline

"The key is that we are making the risks more acceptable by applying modern technology to the age old problem of going quickly on water," says Nigel. "A speed of 300 mph is borderline. If we are to get to the next level we have to understand what happens at the interface between water and air.

"If

Campbell had modern technology it would have saved him. Sensors would

have warned him that the boat was close to taking off." Nigel

Macknight is determined to see his quest through to a successful

conclusion.

He

clearly feels an emotional pull towards Coniston, and bringing the

record home to the Lake District would be a tribute to the memory of

Donald Campbell. But his determination is tempered by caution:

"We will be pretty fired up, but we have to be calculating. The excitement is driving us on, but we have to keep an eye on the science. "We lost the record six months after Donald Campbell died, and we want to bring it back to Britain. "But it's not death or glory."

Nigel MacKnight and Quicksilver

Funding

Seven Technical Partners are providing approximately £1million sponsorship in cash and kind. In addition, 26 Technical Associates are providing approximately £0.5 million sponsorship in cash and kind. Over £350,000 cash has been injected by sponsors, supporters and shareholders to date

Other elements manufactured, but not fitted to Quicksilver at the moment, include the cockpit instrument panel and the (pitot-type) airspeed measurement and indicator system (ASI)

Later this year, more work will be done to complete Quicksilver's on-board systems, under the overall direction of Dr. John Challans. Then, the specification of the craft's hull and sponsons will be upgraded so that the first trials on water can begin. In this initial waterborne form, the craft will be known as Quicksilver Dash 1.

References

British challenger Nigel MacKnight

John Cobb and Crusader on Loch Ness

TRANSIT EXAMPLES - The above table illustrates one of the most likely ocean awareness expedition routes showing the time elapsed in days for 7 knots average cruising speed, including times for 5 and 6 knot averages - allowing for 10% downtime and 36 days in ports. Hence, although the objective is to reduce the current solar circumnavigation record from 584 days, the event in not an outright non-stop yacht competition in the offshore racing sense. It remains to be seen how accurate such a prediction might be.

UK VEHICLE INSURANCE ONLINE A - Z

No matter what car, van or bike you drive, we're all looking for great value and quality in our UK motor insurance? But who is the best - who is the cheapest and who offers the great service in the event of a claim?

See the insurance companies below who claim to offer competitive cover at sensible prices, our guide to the jargon and tips for cutting your quote - Good Luck:-

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | EDUCATION | BLUEPLANET | SOLAR CAR RACING TEAMS | SOLAR CAR RACING TEAMS | SOLAR CARS |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This

website is copyright © 1991- 2019 Electrick Publications. All rights

reserved. The bird logo |