|

JET

HYDROFOIL SHOOTS AT WORLD RECORD

It was during the New York Boat Show of 1952 the

public first heard about Frank and Stella Hanning-Lee.

On the floor at the Old Madison Square Gardens, where

the Boat Show was held, was a stunning hydrofoil boat

obviously designed for high speeds. Yet the story

of the Whie Hawk it's driver and team members has

somehow been overshadowed by the record breaking

community. This is such a shame because it reads

like a film script, includes a fascinating cast of

characters and would indeed make a Howard Hughes (leonardo

di Caprio) style film in typical Hollywood

style. It has it all. A dashing war hero, a glamorous

heroine, secret technology, espionage, intrigue, action,

dramatic accidents and a cruel twist in the tail.

What a thriller!

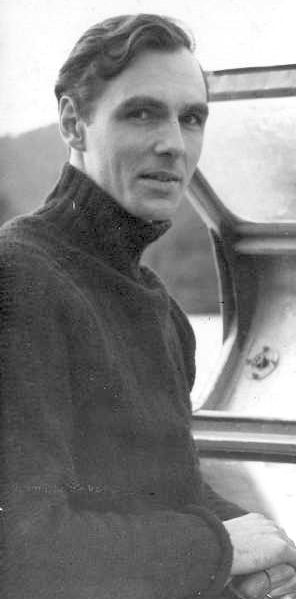

Frank

Hanning-Lee

The

British couple aimed to break the speedboat record

with their jet-powered craft, the White Hawk, on

Lake Mead, Nevada in the fall. The man-and-wife

team collaborated on the design. Mrs. Henning-Lee (an

American by birth) is the driver.

They

have made a hobby of hydrofoils and that is the basis

for their craft. The hydrofoils correspond to the

airfoils or wings of an airplane, lifting the hull

clear of the water to reduce drag at high speeds.

Since water is denser than air, the wings can be much

smaller. The 20 foot White Hawk has a 12-foot

beam. Its Rolls-Royce Derwent jet airplane engine

develops 4000 horsepower.

In

1951, work was in progress on the White Hawk

(registered K5), the jet-powered hydrofoil of a

former submarine lieutenant in the British Navy called

Hanning-Lee. Supported by his beautiful 28-year-old

wife Stella, Frank Hanning-Lee may have inherited the

blind daring of his ancestor, Horatio Nelson, when he

decided to embark on the highly experimental task of

fitting a 1943 Whittle turbojet engine of 2,000 lb.

thrust into the cigar-shaped fuselage of a hydrofoil

configuration, and take a patriotic crack at the water

speed record.

A

propeller-driven boat tends to lift its bow because of

the low position of the thrust. A jet boat tends to

push its bow down into the water (obviously depending

on the aim of the exhaust). To overcome this tendency,

the designers broadened the forward hull. At top

speeds, the hydrofoils keep the nose from burrowing

into the water. It would not have been a giant

leap to have made the lowest foil into a planing shoe,

as used on the Bluebird K7 a few years late by Ken

Norris.

In

the September of 1951, having collected a substantial

amount of data about hydrofoils from both the

Admiralty and Professor Christopher Hook of the

Hydrofoil Association, the Hanning-Lees invited Ken

Norris 'to do their sums for them' and before long

Norris found himself doing the entire design work

himself, until he realised that he was not going to be

paid for his labours.

The

25 ft White Hawk was built and after flotation

and engine tests out on the sea at Margate and on the

Thames at Tilbury, the £14,000 hydrofoil was

transported up to Lake Windermere for trials in the

August of 1952. Apart from a fortnight in September

when they went south to replace the old engine with a

Rolls-Royce Derwent Mark V unit, the Hanning-Lees

stayed at Windermere for three months but were totally

unsuccessful in getting their craft to lift at speeds

much over the 70.86 mph, which Graham Bell's

Hydrodome IV had set up over thirty-three years

before.

Another

Englishman, John Cobb, went after the record in a jet

boat in 1952 and was killed when it exploded during a

speed run. His boat was a flat-bottomed hydroplane

with heavy surface drag. The Henning-Lees say their

hydrofoil design eliminates this danger. But are

there other limitations?

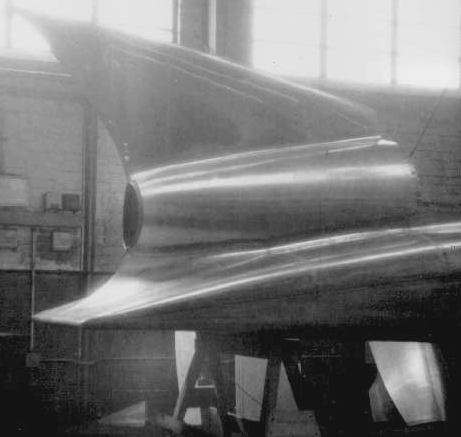

The White

Hawk had

a beautifully made all-aluminum hull. The steel foil

system consisted of a full span U-foil forward and a

single tail foil aft. The aft strut-foil assembly was

steerable. The hull looked like an airplane fuselage and

was wrapped around a Rolls Royce Derwent jet engine. The

Derwent gave the craft a thrust-to-weight ratio greater

than one, so all you had to do was point it skyward and

you had a rocket! The hull contained a single seat cockpit

forward of the gas turbine.

It was advertised that the craft had been brought

to the United States from England with the objective

of seeking the world's speed record for marine craft.

At this time the US Bureau of Aeronautics was

interested in hydrofoils to be used to improve the

landing characteristics of seaplanes in rough water.

Some experimental work was underway funded by the

Bureau and managed out of the Office of Naval

Research. It was decided that the US Navy would make

an investigation into this particular craft and as

Hydrofoil Project Officer, I was given the task of

looking into the vehicle.

Bill Carl (then with John H. Carl and Sons of Long

Island) and Tom Buermann (of Gibbs and Cox) were two

New Yorkers involved with the hydrofoil program. Upon

contacting them regarding the Boat Show hydrofoil,

they both reported that they had seen the craft and

that the owners and operators were Mr. and Mrs.

Hanning-Lee, from England. Both Bill and Tom had

talked with the Hanning-Lees and had learned that they

wanted nothing to do with the US Navy. They were

seeking commercial support and were convinced that

they would be well paid for their efforts. They of

course expressed interest in obtaining any

contributions that Gibbs and Cox or John H. Carl would

care to make.

Frank

was born

into a naval family and educated at Stowe school not

far from the Silverstone grand prix

circuit. At the time Stowe was a fairly

new establishment, former pupils included actor David

Niven. Young Frank was a boarder and studied the

classics, to include Greek and Latin, which is

surprising considering his

later career. He really wanted to be an

engineer not a sailor, but he parents got their way and

in 1937 Frank signed up for a cram course

to teach him all the things he would have learned at Stowe. He was a bright student and came out

top of the class of twenty. Out of those 20

classmates, the other nineteen apparently lost their lives in the

war.

Having joined a ship, Hanning-Lee saw service in

Singapore at the time when Japan was about to invade

and later in submarines before embarking on the

hazards of convoy escort duty to and from the USA. It

was on one of these trips that he met his future

wife.

His

wife Stella was previously a cost-accountant at the Quincy ship yards, near Boston.

She was a striking, attractive,

brunette with a cultured accent and a

strong personality. Their first son, Vaughan,

remembers that his father was very much an ideas-man.

Frank was always inventive,

and loved new technology. He saw the big picture

at the expense

of the day-to-day practicalities. His wife by contrast was very

practical and determined. She was the sort of

character who would push a project along from drawing

board, driving through whatever obstacles got in the

way. Stella is also described as statuesque, with long blond hair and a very business like

attitude. Both had strong British accents and used quite

cultivated English. Mrs. Hanning-Lee

had been born and raised in Connecticut. She met the

Commander during the war, married, and wet to live in

England, where she quickly developed a thick

English accent.

At some point during his naval service,

Lieutenant Hanning-Lee, was inspired by a captured German

torpedo boat which featured hydrofoils to lift it

clear of the drag-inducing water. Frank kept

this in mind and wanted to use the idea in peace time

for a commercial flying boat. I think we can all see

the attraction in that.

Being somewhat impatient by nature he bought

himself out of the Navy 12 months short of his 10 year

service and not only cost himself a good deal of money

but forfeited his future pension rights. Vaughan

Hanning-Lee recalls that this was very much in the

spirit of the time, his father having survived active

service throughout the war when so many colleagues had

perished.

Once in civilian life he went into business, backed up

and pushed forward by Stella, running ex army DUKW

amphibious trucks as a ferry service to and from the

Isle of Wight. Later a boat was built to complement

them, the 220 seat Island Princess. Finance for all of

this probably came from the legacy left to Frank

by his late father in 1947. That same

legacy allowed him to set off on his next

venture, a stepping stone for the promotion of hydrofoils in readiness for

the aircraft he eventually planned to construct - the

White Hawk.

Frank

reckoned that speed record projects gained a

huge amount of publicity at the time and that such a

project would also give credibility to his future

plans and influence potential backers.

Logically, he decided on

attacking the water speed record, which at the time

was held by Sir Malcolm Campbell in the Bluebird

K4 hydroplane, itself something of a British military

secret. The record set by Sir Malcolm in 1939, stood at 141 mph but was

soon to be

broken decisively by Stanley Sayers in the

USA, who pushed the goal posts to a little over

160 mph.

EXPERT

ASSISTANCE

With

his admiralty contacts he was able

to bend the ear of a professor in the west country who

was studying foils for the Navy. Frank went along to

see him and came away armed with performance graphs

and charts which he could base the foil designs upon.

He also touched base with Professor Christopher

Hook of the Hydrofoil society and so acquired more

vital data, some of which was probably a state secret at the time.

However Hanning-Lee, despite his interest in things

mechanical was not a trained engineer and having

conceived a basic layout for the boat contacted

Imperial College, London, to see if they might help

him work out the stresses and structures involved. He

contacted Professor Tom Fink, who in turn passed him

over to a promising student of his who had come to

Imperial after wartime service with Armstrong

Whitworth. This student had worked on projects that

included the top secret "flying wing"

aircraft, his name was Ken

Norris, future designer of both Bluebird K7 and

CN7.

Ken

Norris tells the story in his own words: "Hanning-Lee wanted

some stressing done. So I went along to his

town house, in Chelsea I think, and met him. He took

me into the cellar and showed me some performance

charts and calculations he had got hold of and an

outline drawing of this boat on the wall, complete

with a sharks fin on the top. He said 'Can you stress

that?' and when I said 'Where are the plans?' he just

pointed to the drawing and said 'That's it'. I told

him I needed structural plans to work from - but he

hadn't got any, just this outline. He said 'Can you

draw them for us?' and that's how it started".

Working to the basic concept before him, Ken drew

up a steel square-tube frame clad in aluminium with a

two seat, tandem-style cockpit ahead of the jet

engine, a sleek pointed nose and foils borne on

outriggers either side of the intake. Ken said: "I didn't

know much about hydrodynamics, I was into aircraft and

aerodynamics, my brother Lew was the marine expert so

I asked him and he helped out. I was working for

Hanning-Lee, Lew was already working for Donald

Campbell (on the prop-riding K4) so we were in rival

camps, but he still helped out and so we got on okay with the design".

Ken also used a steel frame and aluminum body for his

Bluebird K7 design.

Frank Hanning-Lee

General consensus has it that Accles & Pollack

built the main framework, probably for a very

advantageous price. When it came to panelling the

boat, the Hanning-Lee's employed a small family firm,

Brownlow Road Sheet Metal Co. based in Willsden. The

company was run by Bert, Harold & Alan Noble and

their day-to-day work consisted of building hearse

bodies!

Vaughan

Hanning-Lee believes that his parents had a deal with

Accles & Pollack to build the hull for a very

advantageous price, maybe even free, but the press of the

day still made hay of the fact it had cost the Hanning-Lees

some £14,000 to get WHITE HAWK to the point of making a

run. During the build, Vaughan also recalls that some work

was done by Bob Sellars, exactly what it was he isn't

sure, but Bob Sellars went on to design part of the

Lightning fighter plane. White Hawk certainly didn't lack

for designers with "the right stuff"! When

complete the craft was floated at Tilbury docks and a

static engine test performed. Then it was loaded onto a

truck which headed north to the lake district. At this

time John Cobb was making the same trip but his boat,

Crusader carried on past the lakes to Loch Ness where he

began extensive test runs. It's interesting that both

boats are exact contemporaries but also that White Hawk was registered as K5 and Crusader as K6. If one assumes

the first non-aircraft use of a jet engine was in

Campbell's unsuccessful Goblin-powered Bluebird K4

"slipper" in 1946-47, White Hawk must rank as

only the second such use and Crusader as the third -

something close to a decade before the concept was applied

to a pukka land speed record vehicle.

In his book

'Water Speed Records', historian Kevin Desmond quotes the boat as using an early Whittle

engine dating from 1943. However, Vaughan Hanning-Lee

is quoted as remembering his father talking of the original Whittle

engine, and there is a photo showing such an engine sitting in the

rear of a space-frame nearing completion, the design of

Ken Norris. Vaughan also confirms that at

some point an approach was made to Rolls Royce about

supplying something more up to date, on the pretext

that any record breaking would be good PR for them

too. It appears the suggestion was persuasive

since not only were Frank and Stella given a Derwent engine, but

they also got a spare,

and a couple of mechanics to work on the engines when

needed.

The team arrived at

Windermere on the weekend of the 17/18 August 1952 and

encountered immediate problems with getting the boat off

the transporter and actually into the water! It took until

Tuesday when a mobile crane was employed to lift it bodily

down into the lake at Bowness pier head, some 500 yards

from it's boathouse. Amid great excitement the engine was

fired and Frank took the controls. This was just a systems

test and the surface was choppy, but he motored the White

Hawk out from the pier a short distance, plumes of spray

almost engulfing it, before cutting the engine. Pushing up

the cockpit cover, he stood up in the seat he waved a

launch over to tow him back as the swell was stronger than

expected. Later in the day the boat was towed across to

the far bank where the trees shielded the wind a little

and a further short run of a few hundred yards was made at

low speed. "It was far too rough ... I doubt whether

I managed to get above 60 mph" he later told the

press. Another run was planned for the following day -

weather permitting. This time White Hawk gave the press

men something to write about when it made a two mile run

with Stella at the controls and Frank in the back-seat.

This was potentially big news, a woman at the wheel of

such a radical craft - not only that but she was young and

glamorous and happened to be American into the bargain!

One can envisage the stir this must have caused in Fleet

Street and indeed there was no shortage of press men on

hand to witness the drama.

Geoff Hallawell, a

regular member of the Bluebird crew from 1949 onwards was

among them, in his capacity as a press photographer.

Hallawell recalls the boat's performance with a chuckle. "it

never actually got going at any speed, it sort of

porpoised up and down with big clouds of spray. He never

saw it go faster that 50 mph. Apparently the

Hanning-Lees did not warm to Geoff, he says they viewed

him with a degree of suspicion and were rather unfriendly,

but admits that his association with Donald Campbell's

team - their direct rival, was probably the cause. Hallawell

recalls that there was a degree of American media

interest in the project, thanks to Stella. This spurred

Associated Press to send along their own cameraman, Les

Priest and Movietone News also saw the potential of the

effort, sending their north-west cameraman Jimmie

Humphries to cover activities on the lake.

Movietone had

once been edited by Sir Malcolm Campbell of course, so

they were naturally always interested in record attempts.

What happened next certainly justified their presence.

Frank took over the controls, Stella alighted and White

Hawk splashed off up the lake again amid clouds of spray

then suddenly at around 60 mph hit the wake of a pleasure

steamer that was moving around. Onlookers saw the sleek

white jet boat suddenly dive headlong into the water and

completely submerge! It bobbed under the surface

swallowing a large volume of water as it did so but

amazingly bobbed back up again, intact! Vaughan Hanning-Lee

recalls his father telling him how it went suddenly quiet

and seemed to take for ever to resurface! The reported

"thousands lining the shores" watched as

launches rushed out to offer assistance. It seemed to be

sinking again, rather slowly, and Frank feared the hull

had been holed. Rapidly a line was attached to tow it back

to the pier. It was a 300 yard trip and they succeeded in

dragging it into the shallows before it actually went

under for the second time.

Reports have it that the craft

was effectively beached in some four feet of water. Ken

Norris, on reading a newspaper clipping of this incident

commented that the boat shouldn't have been run at all if

other craft were moving on the lake, but that it was very

much in the gung-ho spirit of the times that Hanning-Lee

had simply "had a go". In fact it is unclear

what form of team ran the boat, if any. Its possible that

they were reliant on eager locals for the most part to

provide launches and general help with launching White

Hawk, and probably their Rolls Royce mechanics to keep it

running. A later press report mentions "the mechanic

worked until 1am the get the boat ready", giving the

impression that it was something of a one-man operation!.

Certainly there seems to be no record of any organised

troupe of helpers.

A careful check of the

boat was made after it was finally retrieved and Frank

reported "There is no damage done and she will dry

out in a couple of days" but in fact a couple of

large dents were found near the prow and another along the

starboard side which needed repairing. The press had been

told Stella would be making a full out attempt on the

record the following Saturday but the incident effectively

ruled that out. Things then went quiet. The boat was taken

off the lake and repairs and sundry modifications began.

The weather also turned sour - as it always seems to when

any form or record attempt is in progress!

In the meantime Cobb

was undergoing tests on Loch Ness and making good progress

- then disaster. The Crusader nose-dived into the lake and

exploded during the official record attempt and Cobb died

of his injuries. Doubt was cast over the White Hawk

project. Vaughan recalls a lot of reporters hanging around

for a quote, sure that everything would be called off, but

it was announced that the Hanning-Lees would indeed be

going ahead with more trials as soon as the boat and the

weather were in a suitable state to continue. Fatal

accidents in the early 50s were not seen in the same light

as they are today.

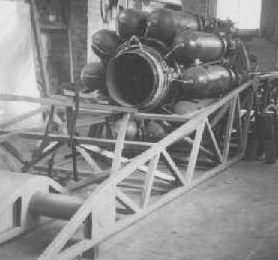

White

Hawk's frame and jet engine

News reports dried up

until early October when Stella was said to have made a

100 mph run but experienced severe "porpoising"

which would require more modifications and a further 5

days to fix as work was carried out not at Windermere, but

in Barrow. On the 18th The Times reported that a new

Derwent engine was being fitted with 6000hp available.

When this was completed the weather had again gone sour

and after only one test run with the new unit in early

November, Frank was quoted as saying he would have to wait

until the lake had been combed for driftwood before more

trials could take place, assuming the weather improved and

the wind dropped. The modifications carried out at Barrow

were said to have cured the porpoising and he denied

stories that they would soon have to pack up and head

south for the winter. Young Vaughan had been attending the

local school and the family had been living in various

local hotels. Almost four moths had now passed since the

early runs, the press had largely gone home, the weather

was unrelentingly dreadful - if it hadn't been strong

wind, it had been fog or rain that caused endless

postponed runs -and money, as always, was running low.

Despite earlier statements Frank & Stella went back to

London in late November, returned briefly in early

December then announced the venture was being put on hold

until at least Easter in the hope of better weather.

FUND

RAISING and the US NAVY

Navy

personnel arranged to meet with the Hanning-Lees to

propose an association, but the couple got the wrong end

of the stick and were somewhat mislead as to the intent of

the meeting, believing private money was being offered -

they rejected any notion of a tie up with the Navy.

Some time went by before we heard anymore about the White

Hawk or the Hanning-Lees, perhaps about three months.

The Hanning-Lees eventually contacted Bill Carl to

rekindle negotiations. Apparently their campaign to raise

funds had not been very successful, having only secured fuel to power the craft for a

speed attempt. They asked Bill Carl if they could

anticipate any support based on our conversations at the

Grammercy Hotel. At which point Bill confessed to

the couple that the meeting had

been an attempt by the US Navy to learn more about them

and their craft. He further revealed to them that a

colleague was a

Naval Officer in the assignment of Hydrofoil Project

Officer with the Office of Naval Research. At this

point the Hanning-Lees said that they no longer had any reservations

about Navy support.

Washington decided to

try and get Frank to make a demonstration run. The

Navy's

proposition was that if the Hanning-Lees would furnish the

craft and pilot, the Navy would pick up the expense for

the other costs for a run over a measured mile. Then, if they

exceeded a speed of 100 miles per hour, the Navy would be

interested in talking to them about a test program. The

Hanning-Lees agreed to this without hesitation, and who

can blame them. It constituted a genuine offer of

sponsorship. Accordingly, the Navy put some extra funds

into what became known as the " John H. Carl and Sons" contract, with Bill

Carl as project manager. Work began on the measured

course shortly thereafter.

Then

the troubles began. After agreeing terms, the Hanning-Lees

confessed to the Navy that they had never run the craft.

Apparently, in

their eagerness to get to the USA to raise funds, they had

left England as soon as the craft was completed. They

didn't even know the last time the turbine had been run,

hence aircraft mechanics would be needed to get the engine

working. The newly formed team sought

help from

Grumman Aircraft, and in particular from Jake Swirbul,

a founder and then president of Grumman. Fortunately, Jake

offered the assistance of not one, but two mechanics.

Since this was for the Navy he even stated that there

would be no cost.

The location chosen for the measured mile was near

Eaton's Neck on the northern shore of Long Island. Here

there was sheltered water and the availability of the US

Coast Guard to assist in the event. The more the team learned

about the craft, the more they became concerned about the

safety of the pilot. There were no instruments on board to

give an indication of speed. Even the turbine's

instrumentation was limited. Further, when the pilot

closed and secured the overhead hatch, it could only be

opened from the inside - so if the pilot was unconscious,

it would be a problem. For this reason the Coast Guard agreed to furnish

a helicopter with a rescue crew on board, with an

axe to break the pilot out in the event of an accident. The

Coast Guard also furnished other boats along the measured

mile to mark the course and for rescue assistance

if required.

Stella

Hanning-Lee

By now the news of the

event had spread throughout the hydrofoil community, and

on the day of the trial about a hundred hydrofoil

enthusiasts had

gathered on Long Island. At last the great day had arrived.

The team selected an early

morning run as the winds were lighter and the sound was

calmer. By about 0630 everyone and everything was in

place.

The night before the trial was most interesting.

The US Navy team had dinner with the Hanning-Lees and the

subject was, ' who would pilot the hydrofoil'. Since both of the Hanning-Lees

were capable. The discussion that followed revealed the

concern both had for the safety of the venture. They

discussed openly who would be the

pilot. Finally, it was decided it would be best for

Commander Hanning-Lee to make the run because in the event

of an accident, Mrs. Hanning-Lee would be able to take

care of their son.

The

Commander was in the White Hawk with the turbine

running nicely about a quarter of a mile before the marker

boat, the start of the measured mile. The signal to go was given and for the

first time White Hawk was underway on its own

power. The craft quickly picked up speed and was

foil-borne

well before reaching the start of the mile. The vessel hit

the start line well up on its foils, running quite stable,

and from the sound of the turbine seemed to be near full

power.

For the next quarter of a mile

the boat appeared to be handling nicely, when all of a

sudden the boat disappeared in

a cloud of white spray. Thankfully, White Hawk

and driver

emerged from the mist afloat and in one piece. Frank

opened the hatch and climbed out quite calmly. But

after the excitement of the halt died down, it emerged

that Frank had no idea of the speed he was going at.

The speed at which the water seemed to be coming at him in

that small space, without any feedback dictated he should

throttle back, if rather suddenly. It seemed like the

sensible thing to do.

A

post-run examination of the craft revealed that everything

was intact except the turbine had ingested quite a bit of

water. This necessitated cleaning before any more running.

Hence, events were called off for the day, and the attempt was

rescheduled for the following morning. The Grumman

mechanics worked diligently through the day and night to

clean the turbine and by dawn the next day the craft was

ready to go. However, the winds had come up over night and

the water over the course was rough. So delaying

testing. Due to the spiraling standby costs the Navy representatives decided that

they could no longer keep the wait going and

called off the trial at Eaton's Neck. However, the

Navy had seen enough

in that short time to want to pursue the matter further.

Thus, the Navy asked Frank and Stella to come forward with a proposal

to permit the Navy to conduct trials at Patuxent Naval Air

Test Center.

Roughly three weeks later, the Hanning-Lees arrived in

Washington with a proposal and brought with them a very pushy lawyer.

Although they didn't know it at the time, their

proposal far exceeded the Navy's budget. The

proposal put forward was based

on an achieved mile per hour basis demonstration. Each

time the speed exceeded certain performance thresholds the

mph cost went up considerably. The cost of

reaching 125 miles per hour along with the living costs

and salaries for both of the Hanning-Lees worked out more

than the US Navy had available. However, instead of

negotiating,

the pushy lawyer demanded an immediate contract. That

had the effect of putting the Navy off and the discussion was

halted. Also, the interest in hydrofoil sea planes was on

the wane. It was just bad timing and the opportunity was

not to come again. Though after cooling off the Hanning-Lees called

the Navy and said they

would be willing to accept any reasonable proposition the Navy would make,

it was no go. It appears they had been overconfident

of their saleability.

RESTING UP

The boat was being stored

at a service station in Silver Spring but even that was

costing more than the Hanning-Lees could afford so it went

back to Stella's mother's in Boston. Popular Mechanics ran

a feature in August 1953 in which it was said to have run

125 mph in England. This is almost certainly not true.

Kevin Desmond quotes no more than 70 mph was recorded and

here we come to the crux of the matter. Ken Norris says

that later experiments with foils showed that above a

certain speed (70-80 mph) the foil "cavitates".

In effect it builds up a low pressure area over the top

surface of the foil and at a given speed this causes the

water to break away from the surface of the foil, much as

an aircraft wing would do in a stall situation. This ruins

the lift, two thirds of it would suddenly vanish and cause

the whole thing to fall back down into the water abruptly.

The foil is designed to run in the water, unlike a

hydroplane and it simply cannot do it's job with the

stall-effect that eventually builds up. Ken says that this

was not appreciated at the time as nothing with foils had

gone anything like as fast as White Hawk. The

experience gained from the craft was therefore very useful

in learning hydrofoil limitations.

This would explain the

porpoising effect that the craft exhibited on Windermere

and may also explain the abrupt end to the Navy trial run.

Where Frank is presumed to have bottled out, what may have

happened is that the boat reached the cavitation point,

fell back into the water and, mindful that any flaw might

ruin a potentially lucrative agreement, Frank may have

decided to shoulder the

blame rather than admit there was a problem with the

design.

It's possible he did

lose his nerve but for a man who had seen so much action

in the war, already experienced one near disaster and

still gone ahead with other runs as if nothing had

happened, this seems out of character. Further to that we

only have the late Bob Johnson's story of the Navy tests

to work from (published on an Internet site) and it's

clear that he wrote the story from memory, some of which

is bound to be rather hazy with the passing of almost 50

years. He states for example that the boat had been built

by the British aircraft industry, that it had never been

run and that it was a single-seater, all of which is

grossly inaccurate. Readers may decide for themselves if Frank

Hanning-Lee lost his nerve, or that

the boat suffered from cavitation as Ken Norris has

predicted.

The Hanning-Lees did

venture out to Nevada and stayed at the Sahara Hotel on

Las Vegas while trying to arrange a run on Lake Mead but

nothing came of this and they returned to Boston and

worked hard to save enough money for a return to Britain.

A

model of White Hawk

BANKRUPT

They had gone broke in trying to

promote their craft and didn't have enough funds to return

them or their craft to England. They had both taken jobs

in retailing to keep their son in school and to save

enough to go home. It seems that on return to England,

they could not afford to pay the import duty then payable,

since the boat had been out of the country of origin for

some time.

Frank finally made it back to Southampton, bringing back

the

boat as cargo in 1954. On arriving he was hen hit by the final

twist of fate - he hadn't the funds to get the White

Hawk through customs! How this situation came

about is unclear, but we can guess there was some rule

about time out of the country. The customs and excise impounded the boat and that is the

last anyone heard of it. Inquiries at the Customs House in

Orchard Place Southampton, yielded a polite and immediate response, that records relating to this period in time have

long-since been destroyed. The department said there

was no

chance of the boat lying undiscovered in the corner of a

warehouse, as the entire docks had been rebuilt since the

50's. It is presumed the craft was sold for

scrap. However, we all know how military secrets are

kept locked away.

Stella and Vaughan

arrived by air some weeks later and picked up the pieces

after their transatlantic adventure. Frank went ahead with

his flying boat idea and contacted Tom Fink at Imperial

once again, but the plane never got off the drawing board.

The experience gained in fibreglass work stood Frank and

Stella in good stead in their later business ventures.

Frank outlived his wife and died in late 1998. Vaughan

went on to study aeronautical engineering at Queen Mary's

while younger brother Mark works in California as a

computer software writer for industry.

The

moral of this story is, if you are considering doing

anything so outrageous, you will go down in the history

books, but nobody will know the personal hardships you may

have suffered along the way, unless you either find

sponsorship, take a record, or die in the process.

Almost all record breakers suffer financially. The

few who didn't, were already wealthy before they started.

The

Hanning-Lees - James Bond takes a back seat

Ken

Norris, who pulled out of the project before the craft

went up to Windermere, explained what happened:

'I

concluded that above a speed of 70 mph, the hydrofoil

would be subject to cavitation. Unlike a hydroplane,

which generates lift by being on top and skating over

the surface, the hydrofoil is immersed fully, generating

lift on both the top and the bottom surface. As the

speed increases, so the pressures round the foil change

until eventually the pressure on the top surface can

become so low that the aerated water tends to create a

complete bubble and break down the lift on the top

surface. At that point one might lose as much as

two-thirds of the lift and at that speed the vessel will

drop back into the water. So it rides up for a start,

gets up to surface speed and then drops down, rather

like a stall with an aeroplane. I believe that this is

what happened to the White Hawk, although this

doesn't mean that their achievement wasn't pretty good.'

The

most cynical comment about the project was that the

Hanning-Lees were really waiting for Lake Windermere to

freeze over so they could then perform on ice-skis!

The sad thing

about all this, is that White Hawk could never have

achieved the outright record as a foil rider, the laws of

physics were simply not going to let it - Ken Norris had

been right. Perhaps the Hanning-Lees should have

been content with the hydrofoil class record!

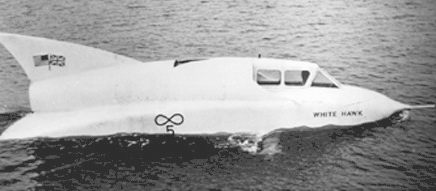

White

Hawk docking

PRESS

REFERENCES CHRONOLOGY

White

Hawk, the £14,000 jet-propelled speedboat, was beached on

the shore of Lake Windermere yesterday. It had

bounced wildly after hitting the wash of a pleasure

steamer while travelling at over 60 m.p.h. in the middle

of the lake.

The

cockpit went under the water as the boat dived nose

first. It bobbed up again and the pilot, ex-naval

officer Mr. Frank Hanning-Lee, climbed out and got astride

the fuselage. Thousand lining the shores saw

pleasure boats secure a rope and tow the White Hawk

300 yards to be beached in 4 ft. of water.

Slight

damage

A

crane lifted the boat out of the water after Mr. Hanning-Lee

and holidaymakers had pumped water from the hull. There

was only superficial damage. Mr. Hanning-Lee said:

"I expected to find a hole. When I struck the wash

water entered the air intake and caused the boat to slew

round and dive.

"It

will take only about a couple of days to dry her out as

the fresh water will not have damaged the engine. Then we

will have another go" The White Hawk was on a

second trial run.

Mr.

Hanning-Lee had taken over from his wife, Stella, who had

piloted it on a two-mile burst.

She

hopes to beat the world water speed record of 178.4 m.p.h.

(The

Daily Graphic, August 21, 1952)

Jet

Boat Takes A Dive At 70 M.P.H.

This

jet-propelled boat was tearing across Lake Windermere at

about 70 m.p.h. yesterday when it began bouncing wildly

over the swell. Before the driver could slow down the boat

dived under the water. It re-appeared almost immediately

but began sinking slowly. Pleasure boats rushed alongside

and the waterlogged boat was towed to the beach. On

Saturday, with Stella Hanning-Lee, 28, at the controls, it

was to have made an attempt on the world water speed

record — 178.49 m.p.h. — held by America. Frank

Hanning-Lee, Stella’s husband, was driving at the time

of the accident. He was unhurt. His wife was driving when

this picture was taken, earlier in the day. After the

accident, Mr Hanning-Lee said: "There is no damage

done and she will dry out in a couple of days."

(The

Daily Mirror, August 21, 1952)

Slight

Mishap to White Hawk -

Future trials only in the early mornings

Hopes

were being entertained last night for a start early this

morning of trials on Windermere by the jet propelled

speedboat, White Hawk, preliminary to the attempt

to snatch the world water speed record from America —

178.4 miles an hour.

White

Hawk, new hope of

ex-submarine lieutenant Frank Hanning-Lee and his wife

Stella, was beached on Wednesday night after it had run

into the wash of a pleasure steamer while travelling at 60

m.p.h. Although no mechanical damage was caused, Mr.

Hanning-Lee revised his plans for water trials and

announced that in future he would take the boat out on the

lake only in the early morning hours.

The

speedboat, the first to attempt the record fitted in

hydrofoils, arrived at Windermere last week-end from the

south but launching difficulties held up trial work until

Tuesday when the craft was towed 500 years from its

boathouse to the pier head at Bowness and lifted bodily

into the water by mobile crane.

The

First Run

Weather

conditions were, however, against the trial — carried

out mainly to test the boat's controls after its trip from

the south — and Mr. Hanning-Lee made only a short run to

Storrs Hall.

After

he had turned the boat round only a few yards out from the

shore, Mr. Hanning-Lee pushed back the cockpit cover,

stood up and waved his hands to indicate to watchers that

the water was too rough.

He

did, however, make a second run on the opposite side of

the lake and in the shelter of a wooded shore, but after

covering only a few hundred yards the White Hawk

was towed back in.

Later,

Mr. Hanning-Lee said: It was far too rough to do anything

and I doubt whether I managed to get above 60 m.p.h."

[text

missing] passenger vessel and the violence of the swell

had caused the hydrofoils to exercise a negative rather

than a positive action with he result that they pulled the

boat under the water. At first it was suspected that

the craft had been holed because it sank so quickly. When

the boat was actually lifted from the water it was seen

that there was very little underwater damage apart from

the two fairly large dents near the prow.

These

were caused by the violence of the impact when the boat

struck the water. As for a small dent on the

starboard side of White Hawk, Mr. Hanning-Lee said

"I don't know how that came to be there."

About

the future, he said that the engine would have to be

pumped out and overhauled, but there did not seem to be

serious structural damage requiring attention.

"There is very little damage done and it is just a

matter of drying out the engine," Mr. Hanning-Lee

later added.

Wife

at Controls

Until

the mishap all had gone quite well with the trials. Both

Mr. Hanning-Lee and his wife Stella — who intends to

pilot White Hawk when a record bid is made — have

admitted that very little is known about hydrofoils.

Mrs.

Hanning-Lee accompanied her husband in the cockpit of the

boat and was seen to be at the controls for the first

trial runs. First test was made towards the southern end

of the lake and later Mrs. Hanning-Lee handed over to her

husband and left the boat.

Mr.

Hanning-Lee said that the mishap would not interfere with

plans for further trials.

He

gave no figure of the speed at which his boat travelled

during yesterday's tests.

(Late

August, 1952)

Attempt

On Water Speed Record To Go On

It

was stated yesterday that Mr. and Mrs. F. Hanning-Lee

intend to carry on with their attempts on the world water

speed record of 178.4 m.p.h. on Windermere. At present

their 3,000 h.p. jet-powered speedboat White Hawk

is confined to the boathouse while minor alterations are

being made to the stern hydrofoil.

(The

Times, October 1, 1952)

Record

attempt. Mr. and Mrs. Hanning-Lee in their jointly

designed jet-propelled speedboat at Lake Windermere, where

they hope to set up a new world water speed record when

weather permits.

(The

Telegraph October 6, 1952)

White

Hawk, Jet Challenger, Flashes By — With A 28-Year-Old

Mother At The Wheel

White

Hawk, jet

challenger for the world's water-speed record of 178.49

miles an hour swishes across the waters of Lake Windermere

at more that 100 miles an hour in a test run — with

Stella Hanning–Lee, 28-year-old mother, at the wheel.

She and her husband Frank have been seven weeks at

Windermere. Yesterday it was said there would be a

five-day delay in trials while further modifications are

carries out to try to correct "porpoising"

tendencies of the boat while travelling at speed.

(The

Express, October 10, 1952)

Ready

For An Attempt on the World Water-Speed Record : Mrs. F.

Hanning-Lee With Her Husband Aboard White Hawk on

Lake Windermere.

Mr.

and Mrs. F. Hanning-Lee have been waiting for some weeks

to attempt to raise the world water-speed record in their

3,000-h.p. jet-powered speedboat White Hawk on

Lake Windermere. They designed the aluminium boat

themselves and expect to reach 200 m.p.h. in her. On

October 3 Mr. Hanning-Lee stated that his wife would pilot

the boat when the attempt was made.

(The

Illustrated London News, October 18, 1952)

New

Engine for Speed Boat

A

new jet engine is to be fitted to the boat White Hawk,

with which Mr. and Mrs Frank Hanning-Lee hope to break the

world's water speed record on Windermere. The new engine

is a 6,000 h.p. Rolls-Royce Derwent Mark V. Further

modifications will also be made to improve the boat's

stability at speed

(The

Times, October 18, 1952)

Still

They Wait at Windermere - Bad Weather Delays Jet-Boat

Trials

White

Hawk, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hanning-Lee's jet-propelled

speedboat, has been confined to her Bowness boathouse all

this wee, because of the rough weather. The boat has not

had a trial since being refitted with a new engine last

week. Mr. Hanning-Lee said yesterday (Thursday) that he is

determined to wait until there is an improvement in the

weather.

Following

the stormy weather there is a possibility of much

driftwood having found its way into the lake. Although Mr.

Hanning-Lee has decided that the course should be

thoroughly "combed" before any trial run, there

remains the fact that larger pieces of timber, when

thoroughly waterlogged, float just beneath the surface and

are invisible from a boat.

(The

Gazette, November 1, 1952)

Mr.

Frank Hanning-Lee who has been waiting at Windermere for

the weather to improve to test the new 6,000 h.p. jet

engine installed in his speed boat White Hawk has

denied rumours that he is postponing trials until next

year and that he and his wife, Stella, intend leaving

Windermere in the near future.

(The

Barrow News, November 1, 1952 )

Water

Record Bid Put Off - Speed

Trials hampered

An

attempt on the world water speed record on Lake Windermere

by Mr. and Mrs Frank Hanning-Lee, in their jet-propelled

speedboat White Hawk, has been postponed. Bad

weather has hampered the trial. Mr. Hanning-Lee, whose

home is in Chelsea, S.W., has not officially abandoned his

record bid, but his friends believe he will soon take the White

Hawk south and return next summer.

(November

10, 1952)

Jet-Propelled

Speedboat in Test Run: The Whitehawk

[sic], which looks like a seaplane, streaking along at 100

miles an hour [sic] on Lake Windermere, England. Test was

made in preparation for the attempt on the world's water

speed record by Frank Hanning-Lee and his wife. The

official world mark is 178.497 m.p.h.

(

New York Times, November 14, 1952)

White

Hawk Trials

Decision this

week-end?

Mr.

Frank Hanning-Lee is expected to return to Windermere

tomorrow (Saturday), but it is not yet known whether or

not he intends to conduct further trials this year with

his speedboat, White Hawk. for a fortnight the

jet-powered boat has remained in the boathouse since

having only one trial run to test her new engine.

Mr.

Hanning-Lee, and his wife, Stella, who was to have made an

attempt on the world's water speed record, came up to

Windermere nearly three months ago.

(The

Gazette, November 15, 1952)

Is

White Hawk winter-bound?

It

now seems unlikely that there can be further trials of the

jet propelled speedboat White Hawk on Windermere.

Rapidly worsening weather conditions have so far prevented

Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hanning-Lee taking the boat on the lake

more than once since further modifications were made at

Barrow and a new engine fitted a week or two ago.

Local

opinion holds that the onset of November makes it far too

late to hope for a calm lake or for any favourable weather

conditions, and while there has been no statement from Mr.

and Mrs. Hanning-Lee, who have been in London for a few

day, it is thought that they will take their craft south

very shortly.

Hitherto

Mr. Hanning-Lee has denied that he and his wife intend

abandoning their attempt on the world water speed record

for this year, but the signs now are that the weather will

defeat them.

(November

15, 1952)

White

Hawk may be "rested" till next year

Although

Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hanning-Lee are still in London, their

jet propelled speedboat White Hawk remains in the

boat house at Bowness, where it was brought from the South

of England for an attack on the world water speed

record. The Hanning-Lees' plans are unknown.

Certainly White Hawk has not been on Windermere for

tests for some time but whether the attempt to set a new

record has been abandoned for this year has not yet been

announce.

November

is regarded as an unfavourable month because of the risk

of mist and, with the advent of chill winds and frost, the

chance that patches of ice may form on the lake

surface. It was reported recently that the Hanning-Lees

might be forced by the weather to postpone further

attempts until next year. This boat has been fitted with a

more powerful engine and has been modified twice since

being brought North.

It

is understood that the Hanning-Lees' young son is

attending school at Windermere.

(Source?

November 29, 1952)

News

in Brief

Mr.

Frank Hanning-Lee said at Windermere on Saturday that he

and his wife had postponed until next year their attempt

to beat the world's water speed record.

(The

Times, December 1, 1952)

Trials

off until Easter Windermere Jet-boat Decision

Mr.

Frank Hanning-Lee returned to Windermere last week-end

when he announce that he and his wife had decided to

abandon trials with their speedboat White Hawk for

this year. The boat is to be ta

ken

south and various adjustments will be made during the

winter, but Mr. Hanning-Lee said he and his wife hope to

resume trials at Easter.

On

Monday, the jet-powered boat was taken up the lake to

Calgarth where she was hoisted on a road trailer and

brought back to Bowness to await the journey south.

(The

Gazette, December 6, 1952)

Jet-boat

has fastest trial run

Mrs.

Stella Hanning-Lee (28), who is to pilot the 3,000 h.p.

jet-boat White Hawk in an attempt on the world

water speed record on Windermere, was not present

yesterday when her husband, Mr. Frank Hanning-Lee, had his

fastest trial run of more than 100 m.p.h.

Mr.

Hanning-Lee said afterwards: "Although my air speed

gauge was out of commission, I was certain that White

Hawk travelled at well over 100 m.p.h. Recent

modifications have proved successful, and today the boat

rode perfectly. "I intend to travel faster each

day, and hope to call in the official timekeepers at the

weekend.

White

Hawk does 110 -

Speed tests on Windermere Jet-Boat "Steady"

White

Hawk, the 3,000

h.p. jet boat, piloted by Mr. Frank Hanning-Lee, traveled

faster than ever before in a test on Windermere on Sunday

morning. This was her first real trial since modification

at Barrow and Mr. Hanning-Lee is satisfied that the "porpoising"

tendency has been remove. He estimated his speed on that

run as in the region of 110 miles an hour.

The

boat now travels with a steadiness which was conspicuous

by its absence in previous trial runs.

Further

modifications may be necessary to increase the directional

stability of the revolutionary craft, but this is not

likely to cause serious delay. Some defect in the fuel

feed system has also to be corrected.

Mist

Delayed Wednesday Trial

On

Wednesday a heavy blanket of mist reduced visibility to an

absolute minimum, and thought the mechanic had worked

until 1 a.m. to get the boat ready, it was not possible to

have a run until after 11 o'clock. The engine was started

with difficulty, and the boat then did a run north of Hen

Holme, after which she was towed back because of an

air-lock in the fuel supply. It is hoped to resume trials

on Friday.

Mr.

Hanning-Lee confirmed this week that the actual bid on the

world's water speed record would be made by his

28-years-old wife, Stella.

White

Hawk

Mr.

and Mrs. Hanning-Lee have taken their jet-propelled

hydrofoil boat White Hawk to the U.S.A. They hope

to make an attempt on the world speed record.

When

they arrived in Massachusetts they had plans to renew

their attack on the water speed record "at Lake Mead

or some lake in Florida, sometime next month."

(Motor

Boat & Yachting, March 1953)

LINKS

:

Hydroplanes

and Racing:

Hydrofest

Hyrdroplane

& Raceboat Musuem

World

Water Speed Records

Hydros

Seattle

Outboard Association

|