|

My

creative art tutor urged me to read Mr McEwan's 'Solar', as an exercise

and to critic. Shortly after that I read Atonement, which blew me

away - it was almost exactly the same as the film, which was superbly

interpreted and acted, testament to the film's director, but also

telling as to the effect that the book had upon those who read it. So

much so that they wanted to reproduce it faithfully..

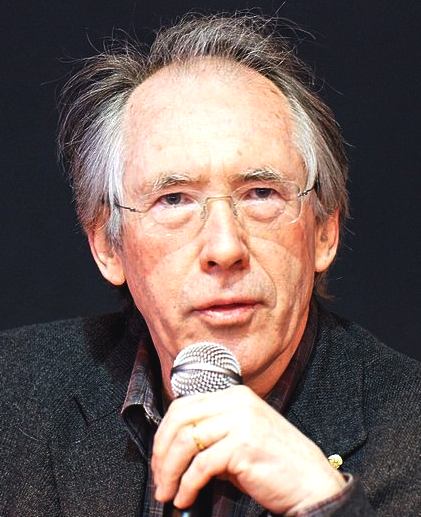

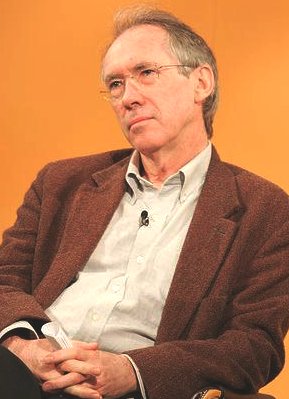

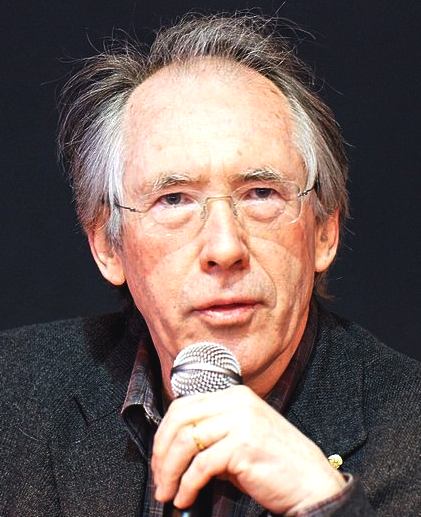

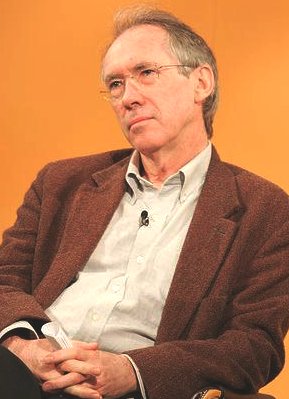

Ian Russell

McEwan CBE, FRSA, FRSL (born 21 June 1948) is a British novelist and screenwriter, and one of Britain's most highly regarded writers. In 2008, The Times named him among their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".

McEwan began his career writing sparse, Gothic short stories. The Cement Garden (1978) and The Comfort of Strangers (1981) were his first two novels, and earned him the nickname "Ian Macabre". These were followed by three novels of some success in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 1997, he published Enduring Love, which was made into a film. He won the Man Booker Prize with

Amsterdam (1998). In 2011, he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize. In 2001, he published Atonement, which was made into an

Oscar-winning film. This was followed by Saturday (2003), On Chesil Beach (2007) and Solar (2010).

Early life

McEwan was born in Aldershot, Hampshire, on 21 June 1948, the son of David McEwan and Rose Lilian Violet (née

Moore). He spent much of his childhood in East Asia (including Singapore), Germany and North Africa (including Libya), where his father, a Scottish army officer, was posted. His family returned to England when he was twelve. He was educated at Woolverstone Hall School; the University of

Sussex, receiving his degree in English literature in 1970; and the University of East Anglia, where he was one of the first graduates of Malcolm Bradbury's pioneering creative writing course.

Career

McEwan's first published work was a collection of short stories, First Love, Last Rites (1975), which won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1976. He achieved notoriety in 1979 when the BBC suspended production of his play Solid Geometry because of its supposed

obscenity. His second collection of short stories, In Between the Sheets, was published in 1978. The Cement Garden (1978) and The Comfort of Strangers (1981) were his two earliest novels, both of which were adapted into films. The nature of these works caused him to be nicknamed "Ian

Macabre". These were followed by The Child in Time (1987), winner of the 1987 Whitbread Novel Award; The Innocent (1990); and Black Dogs (1992). McEwan has also written two children's books, Rose Blanche (1985) The Daydreamer (1994).

His 1997 novel, Enduring Love, about the relationship between a science writer and a stalker, was popular with critics, although it was not shortlisted for the Booker

Prize. It was adapted into a film in 2004. In 1998, he won the Man Booker Prize for

Amsterdam. His next novel, Atonement (2001), received considerable acclaim; Time magazine named it the best novel of 2002, and it was shortlisted for the Booker

Prize. In 2007, the critically acclaimed movie Atonement, directed by Joe Wright and starring

Keira Knightley and

James McAvoy, was released in cinemas worldwide. His next work, Saturday (2003), follows an especially eventful day in the life of a successful neurosurgeon. Saturday won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for 2005, and his novel On Chesil Beach (2007) was shortlisted for the 2007 Booker Prize. McEwan has also written a number of produced screenplays, a stage play, children's fiction, an oratorio and a libretto titled For You with music composed by Michael Berkeley.

Solar, was published by Jonathan Cape and Doubleday in March 2010. In June 2008 at the Hay Festival, McEwan gave a surprise reading of this work-in-progress. The novel concerns "a scientist who hopes to save the

planet." from the threat of climate change, with inspiration for the novel coming from a trip McEwan made in 2005 "when he was part of an expedition of artists and scientists who spent several weeks aboard a ship near the north pole to discuss environmental concerns". McEwan noted "The novel's protagonist Michael Beard has been awarded a Nobel prize for his pioneering work on physics, and has discovered that winning the coveted prize has interfered with his

work". He said that the work was not a comedy: "I hate comic novels; it's like being wrestled to the ground and being tickled, being forced to

laugh", instead, that it had extended comic stretches. McEwan is working on his twelfth novel, historical in nature and set in the

1970s.

In 2006 he was accused of plagiarism; specifically that a passage in Atonement (2001) closely echoed a passage from a memoir, No Time for Romance, published in 1977 by Lucilla Andrews. McEwan acknowledged using the book as a source for his

work. McEwan had included a brief note at the end of Atonement, referring to Andrews’s autobiography, among several other

works. Writing in The Guardian in November 2006, a month after Andrews' death, McEwan professed innocence of plagiarism while acknowledging his debt to the

author. Several authors defended him, including John Updike, Martin Amis, Margaret Atwood, Thomas Keneally, Kazuo Ishiguro, Zadie Smith, and Thomas

Pynchon.

Awards and honours

McEwan has been nominated for the Man Booker prize six times to date, winning the Prize for Amsterdam in 1998. His other nominations were for The Comfort of Strangers (1981, Shortlisted), Black Dogs (1992, Shortlisted), Atonement (2001, Shortlisted), Saturday (2005, Longlisted), and On Chesil Beach (2007, Shortlisted). McEwan also received nominations for the Man Booker International Prize in 2005 and

2007.

He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, a Fellow of the Royal Society of

Arts, and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was awarded the Shakespeare Prize by the Alfred Toepfer Foundation, Hamburg, in 1999. He is also a Distinguished Supporter of the British Humanist Association. He was awarded a CBE in

2000. In 2005, he was the first recipient of Dickinson College's prestigious Harold and Ethel L. Stellfox Visiting Scholar and Writers Program

Award, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In 2008, McEwan was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Literature by

University College, London, where he used to teach English literature. In 2008,

The Times named McEwan among their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since

1945".

In 2010, McEwan received the Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award. The Helmerich Award is presented annually by the Tulsa Library Trust.

On 20 February 2011, he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in

Society. He accepted the prize, despite controversy and pressure from groups and individuals opposed to the

Israeli

government. McEwan responded to his critics, and specifically the group British Writers in Support of Palestine (BWISP), in a letter to

The Guardian, stating in part, "There are ways in which art can have a longer reach than politics, and for me the emblem in this respect is Daniel Barenboim's West-Eastern Divan Orchestra – surely a beam of hope in a dark landscape, though denigrated by the Israeli religious right and Hamas. If BWISP is against this particular project, then clearly we have nothing more to say to each

other." McEwan's acceptance speech discussed the complaints against him and provided further insight into his reasons for accepting the

award. He also said he will donate the amount of the prize, "ten thousand dollars to Combatants for Peace, an organisation that brings together Israeli ex-soldiers and Palestinian

ex-fighters."

Personal

life

He has been married twice. His second wife, Annalena McAfee, was formerly the editor of The Guardian's Review section. In 1999, his first wife, Penny Allen, took their 13-year-old son to

France after a court in Brittany ruled that the boy should be returned to his father, who had been granted sole custody over him and his 15-year-old

brother.

In 2002, McEwan discovered that he had a brother who had been given up for adoption during

World War II; the story became public in

2007. The brother, a bricklayer named David Sharp, was born six years earlier than McEwan, when his mother was married to a different man. Sharp has the same parents as McEwan but was born from an affair between them that occurred before their marriage. After her first husband was killed in combat, McEwan's mother married her lover, and Ian was born a few years

later. The brothers are in regular contact, and McEwan has written a foreword to Sharp's memoir.

Views on religion and politics

In 2008, McEwan publicly spoke out against Islamism for its views on women and on homosexuality. He was quoted as saying that fundamentalist Islam wanted to create a society that he "abhorred". His comments appeared in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, to defend fellow writer Martin Amis against allegations of racism. McEwan, an

atheist, said that certain streams of Christianity were "equally absurd" and that he didn't "like these medieval visions of the world according to which God is coming to save the faithful and to damn the

others."

McEwan put forward the following statement on his official site and blog after claiming he was misinterpreted:

Certain remarks of mine to an Italian journalist have been widely misrepresented in the UK press, and on various websites. Contrary to reports, my remarks were not about Islam, but about Islamism – perhaps 'extremism' would be a better term. I grew up in a Muslim country – Libya – and have only warm memories of a dignified, tolerant and hospitable Islamic culture. I was referring in my interview to a tiny minority who preach violent jihad, who incite hatred and violence against 'infidels', apostates, Jews and homosexuals; who in their speeches and on their websites speak passionately against free thought, pluralism, democracy, unveiled women; who will tolerate no other interpretation of Islam but their own and have vilified Sufism and other strands of Islam as apostasy; who have

murdered, among others, fellow Muslims by the thousands in the market places of Iraq, Algeria and in the Sudan. Countless Islamic writers, journalists and religious authorities have expressed their disgust at this extremist violence. To speak against such things is hardly 'astonishing' on my part (Independent on Sunday) or original, nor is it 'Islamophobic' and 'right wing' as one official of the Muslim Council of Britain insists, and nor is it to endorse the failures and brutalities of

U.S. foreign policy. It is merely to invoke a common humanity which I hope would be shared by all religions as well as all

non-believers.'

In 2008, McEwan was among a list of more than 200,000 writers of a petition to support Roberto Saviano, in exposing the Neapolitan mafia in the book Gomorrah. The petition urges Italian police to assure the full protection of Saviano from the mafia, while comparing the mob's threats against Saviano to "the tactics used by extremist religious

groups".

McEwan lent his support to the campaign to release Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, the Iranian woman sentenced to death by stoning after being convicted of committing

adultery.

On winning the Jerusalem Prize, McEwan defended himself against criticism for accepting the prize in light of opposition to Israeli policies, saying "If you didn't go to countries whose foreign policy or domestic policy is screwed up, you'd never get out of

bed". On accepting the honour he spoke in favour of Israel's existence, security, and

freedoms while strongly attacking Hamas, as well as Israel's policies in Gaza, and the expansion of

settlements, notable as the audience included political leaders such as Israeli President Shimon Peres and Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat. He also personally attended a protest against the expansion of Israeli settlements on Palestinian

territory.

In 2009 McEwan joined the 10:10 project, a movement that supports positive action on

climate change by encouraging people to reduce their

carbon emissions.

SOLAR

Solar is the story of

Nobel Laureate, Michael Beard. Once a hero and now repeatedly married, overweight, balding and never having quite got to where he might have been.

McEwan's brilliance is in creating characters who are frustrated and flawed. People who could have been heroes but really aren't, and then telling us of how their lives fall apart. When you read Atonement you watch the characters trying to sort their lives out but it all frays apart and the justice you're crying out for never comes. Beard's life is one great disappointment. A Nii Lamptey of the science world, the next big star who never fulfilled his potential.

Solar tells the story of how his life of mediocrity reaches new levels as his personal and private lives collide, set against a backdrop of climate change science in the Noughties, in three parts set in 2000, 2005 and 2009. McEwan kept me reading, kept me hoping and provides the right kind of ending.

McEwan knows how to write in an Ecclesiastes world instead of in Hollywood, a world where happy endings are uncommon rather than normal, where the main character might not be a hero, a man whose best days aren't ahead but long behind him, where personality flaws and circumstances conspire against us rather than giving us everything on a plate, a world where change might really be possible but where no one really has the will or the power to do anything.

Solar is not a particularly cheery beach read, but it's a story for our times.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Novels

The Cement Garden (1978)

The Comfort of Strangers (1981)

The Child in Time (1987)

The Innocent (1990)

Black Dogs (1992)

Enduring Love (1997)

Amsterdam (1998)

Atonement (2001)

Saturday (2005)

On Chesil Beach (2007)

Solar (2010)

Short story collections

First Love, Last Rites (1975)

In Between the Sheets (1978)

The Short Stories (1995)

Children's

fiction

Rose Blanche (1985)

The Daydreamer (1994)

Plays

The Imitation Game (1981)

Screenplays

Jack Flea's Birthday Celebration (1976)

The Ploughman's Lunch (1985)

Sour Sweet (1989)

The Good Son (1993)

Oratorioor Shall We Die? (1983)

LibrettoFor You (2008)

Film

adaptations

Last Day of Summer (1984)

The Cement Garden (1993)

The Comfort of Strangers (1990)

The Innocent (1993)

Solid Geometry (2002)

Enduring Love (2004)

Atonement (2007)

LINKS:

McEwan

Official website

Official

blog

Guardian

Books profile 22 July 2008

The

New Yorker article 23 February 2009

Interview

with McEwan. BBC Video (30 mins)

Powells.com

interview

Salon.com

interview 1998

"Ian

McEwan, The Art of Fiction". Paris Review. Summer 2002

No. 173

Ian

McEwan interview with Charlie Rose, 1 June 2007 (Video, 26

mins)

Unedited

interview with Professor Richard Dawkins

Audio:

Ian McEwan reading from On Chesil Beach at the 2007 Key West

Literary Seminar

Ian

McEwan presents "Solar" in Barcelona, Canal-L

NOVELIST

INDEX

A - Z

GRAPHIC

NOVEL INDEX

A - Z

New

energy drinks for performers

..

Thirst for Life

330ml

Earth can - the World in Your Hands

|