|

GEORGE WASHINGTON

|

||||||||||||

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | BOOKS | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | NEWS | SOLAR BOATS | SPORTS |

||||||||||||

|

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) led America's Continental Army to victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and was later elected the first president of the United States under the U.S. Constitution. He served two four-year terms from 1789 to 1797, winning reelection in 1792. Because of his central and critical role in the founding of the United States, Washington is referred to as father of the nation. His devotion to republicanism and civic virtue made him an exemplary figure among early American politicians.

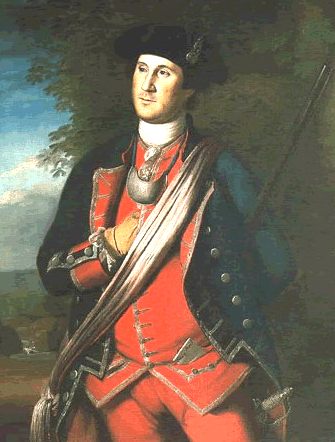

Earliest portrait of Washington, painted in 1772 by Charles Willson Peale, shows Washington in uniform as colonel of the Virginia Regiment

In his youth, Washington worked as a surveyor of rural lands and acquired what would become invaluable knowledge of the terrain around his native state of Virginia. Washington gained command experience during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). Due to this experience, his military bearing, his enormous charisma, his leadership of the patriot cause in Virginia, and his political base in the largest colony, the Second Continental Congress chose him, in 1775, as their commander-in-chief of the American army.

In 1776, he victoriously forced the British out of Boston. But, later that same year, was badly defeated, and nearly captured, when he lost New York City. However, in the bitter-cold dead of night, he revived the patriot cause, by crossing the Delaware river in New Jersey and defeating the surprised enemy units. As a result of his strategic oversight, Revolutionary forces captured the two main British combat armies, first at Saratoga in 1777 and then at Yorktown in 1781. He handled relations with the states and their militias, dealt with disputing generals and colonels, and worked with Congress to supply and recruit the Continental army. Negotiating with Congress, the colonial states, and French allies, he held together a tenuous army and fragile birthing nation, amid the constant threats of disintegration and failure. He was also the country's first spymaster.

Following the end of the war in 1783, Washington emulated the Roman general Cincinnatus, and retired to his plantation on Mount Vernon, an exemplar of the republican ideal of citizen leadership who rejected power. Alarmed in the late 1780s at the many weaknesses of the new nation under the Articles of Confederation, he presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the much stronger United States Constitution in 1787.

In 1789, Washington became President of the United States and promptly established many of the customs and usages of the new government's executive department. He sought to create a great nation capable of surviving in a world torn asunder by war between Britain and France. His Proclamation of Neutrality of 1793 provided a basis for avoiding any involvement in foreign conflicts. He supported Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton's plans to build a strong central government by funding the national debt, implementing an effective tax system, and creating a national bank. When rebels in Pennsylvania defied Federal authority, he rode at the head of the army to authoritatively quell the Whiskey Rebellion. Washington avoided the temptation of war and began a decade of peace with Britain via the Jay Treaty in 1795; he used his immense prestige to get it ratified over intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although he never officially joined the Federalist Party, he supported its programs and was its inspirational leader. By refusing to pursue a third term, he made it the enduring norm that no U.S. President should seek more than two. Washington's Farewell Address was a primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against involvement in foreign wars.

As the symbol of republicanism in practice, Washington embodied American values and across the world was seen as the symbol of the new nation. Scholars perennially rank him among the three greatest U.S. Presidents. During Washington's funeral oration, Henry Lee said that of among all Americans, he was "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

Early life

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 (February 11, 1731, O.S.), the first son of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington, on the family estate (later known as Wakefield) in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Of a wealthy family with firm roots in the Old Country, Washington embarked upon a career as a planter and in 1748 was invited to go with the party that was to survey Baron Fairfax's lands west of the Blue Ridge. In 1749 he was appointed to his first public office, surveyor of newly created Culpeper County, and through his half-brother Lawrence Washington he became interested in the Ohio Company, which had as its object the exploitation of Western lands. After Lawrence's death (1752), George inherited part of his estate and took over some of Lawrence's duties as adjutant of the colony. As district adjutant, which made (December 1752) him Major Washington at the age of 20, he was charged with training the militia in the quarter assigned him. In Fredricksburg, also at the age of 20, Washington joined the Freemasons, a fraternal organization that became a lifelong influence.

French and Indian War

At 22 years of age Washington fired some of the first shots of the French and Indian War, soon to become part of the worldwide Seven Years' War. The trouble began in 1753, when France began building a series of forts in the Ohio Country, a region also claimed by Virginia. Governor Dinwiddie sent young Major Washington to the Ohio Country to assess French military strength and intentions, and ask the French to leave. When the French refused, Washington's published report was widely read in both Virginia and Britain. In 1754, Dinwiddie sent Washington, now commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in the newly created Virginia Regiment, to drive the French away. Along with his American Indian allies, Washington and his troops ambushed a French scouting party of some 30 men led by Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville, sent from Fort Duquesne to discover if Washington had in fact invaded French-claimed territory. Were this to be the case he was to send word back to the fort, then deliver a formal summons to Washington calling on him to withdraw. His small force was an embassy, resembling Washington’s to Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre the preceding year, and he neglected to post sentries around his encampment. At daybreak on the 28th, Washington with 40 men stole up on the French camp near present Jumonville, Pa. Some were still asleep, others preparing breakfast. Without warning, Washington gave the order to fire.

The Canadians who escaped the volley scrambled for their weapons, but were swiftly overwhelmed. Jumonville, the French later claimed, was struck down while trying to proclaim his official summons. Ten of the Canadians were killed, one wounded, all but one of the rest taken prisoner. Washington and his men then retired, leaving the bodies of their victims for the wolves. Washington then built Fort Necessity, which soon proved inadequate, as he was soon compelled to surrender to a larger French and Indian force. The surrender terms that Washington signed included an admission that he had assassinated Jumonville. Because the French claimed that Jumonville's party had been on a diplomatic (rather than military) mission, the "Jumonville affair" became an international incident and helped to ignite a wider war. Washington was released by the French with his promise not to return to the Ohio Country for one year. Back in Virginia, Governor Dinwiddie broke up the Virginia Regiment into independent companies; Washington resigned from active military service rather than accept a demotion to captain.

In 1755, British General Edward Braddock headed a major effort to retake the Ohio Country. Washington eagerly volunteered to serve as one of Braddock's aides, although the British officers held the colonials in contempt. The expedition ended in disaster at the Battle of the Monongahela. Washington distinguished himself in the debacle—he had two horses shot out from under him, and four bullets pierced his coat—yet, he sustained no injuries and showed coolness under fire. While Washington's exact leadership role during the battle has been debated, biographer Joseph Ellis asserts that Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnant of the British and Virginian forces to a retreat. In Virginia, Washington was acclaimed as a hero.

In fall 1755, Governor Dinwiddie appointed Washington commander in chief of all Virginia forces, with rank of colonel, with responsibility for defending 300 miles (480 km) of mountainous frontier with about 300 men. Washington supervised savage, frontier warfare that averaged two engagements a month. His letters show he was moved by the plight of the frontiersmen he was protecting. With too few troops and inadequate supplies, lacking sufficient authority with which to maintain complete discipline, and hampered by an antagonistic governor, he had a severe challenge. In 1758, he took part in the Forbes Expedition, which successfully drove the French away from Fort Duquesne.

Washington's goal at the outset of his military career had been to secure a commission as a British officer, which had more prestige than serving in the provincial military. However, the British officers had disdain for the amateurish, non-aristocratic Americans. Washington's commission never came; in 1758, Washington resigned from active military service and spent the next sixteen years as a Virginia planter and politician.

Between the wars

On January 6, 1759, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow. They had a good marriage, and together raised her two children, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jackie" and "Patsy". Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together—his earlier bout with smallpox followed, possibly, by tuberculosis may have made him sterile. The newlywed couple moved to Mount Vernon, where he took up the life of a genteel planter and political figure.

Washington's marriage to a wealthy widow greatly increased his property holdings and social standing. He acquired one-third of the 18,000-acre (73 km²) Custis estate upon his marriage, and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children. He frequently purchased additional acreage in his own name, and was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775, Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres (26 km²), with over 100 slaves. As a respected military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.

Washington first took a leading role in the growing colonial resistance in 1769, when he introduced a proposal drafted by his friend George Mason which called for Virginia to boycott imported English goods until the Townshend Acts were repealed. Parliament repealed the Acts in 1770. Washington regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges". In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the Fairfax Resolves were adopted, which called for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress. In August, he attended the First Virginia Convention, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.

American Revolution

After fighting broke out in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. Washington had the prestige, the military experience, the charisma and military bearing, the reputation of being a strong patriot, and he was supported by the South, especially Virginia. There was no serious competition. Congress created the Continental Army on June 14; the next day on the nomination of John Adams of Massachusetts it selected Washington as commander-in-chief. Washington assumed command of the American forces in Massachusetts in July 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Realising his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. British arsenals were raided (including some in the West Indies) and some manufacturing was attempted; a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) was obtained by the end of 1776, mostly from France.

Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston and Washington moved his army to New York City.

As Bickham (2002) shows, Washington was widely admired in Britain, where the press was virtually unanimous in portraying him in a positive light. Although negative toward the patriots in the Continental Congress, British newspapers routinely praised Washington's personal character and qualities as a military commander. Moreover, both sides of the aisle in Parliament found the American general's courage, endurance, and attentiveness to the welfare of his troops worthy of approbation and examples of the virtues they and most other Britons found wanting in their own commanders. Washington's refusal to become involved in politics buttressed his reputation as a man fully committed to the military mission at hand and above the factional fray.

In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a massive naval and land campaign to capture New York designed to seize New York City and offer a negotiated settlement. Several defeats against Howe sent Washington scrambling out of New York and across New Jersey, leaving the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey.

Washington was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. On September 26, Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched into Philadelphia unopposed. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in early October. Meanwhile Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army at Saratoga. The victory caused France to enter the war as an open ally, turning the Revolution into a major world-wide war. Washington's loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing Washington from command. This episode failed after Washington's supporters rallied behind him.

Washington's army encamped at Valley Forge in December 1777, where it stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff. The British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York City. Meanwhile, Washington remained with his army outside New York. He delievered the final blow in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781 marked the end of fighting. The Treaty of Paris (1783) recognized the independence of the United States.

In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of Army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers. A few days later, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession of the city; at Fraunces Tavern in the city on December 4, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation.

Washington's retirement to Mount Vernon was short-lived. He was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, and he was unanimously elected president of the Convention. For the most part, he did not participate in the debates involved (though he did participate in voting for or against the various articles), but his prestige was great enough to maintain collegiality and to keep the delegates at their labors. The delegates designed the presidency with Washington in mind, and allowed him to define the office once elected. After the Convention, his support convinced many, including the Virginia legislature, to vote for ratification; all 13 states did ratify the new Constitution.

Washington in Mount Rushmore

Presidency: 1789–1797

Washington was elected unanimously by the Electoral College in 1789, and he remains the only person ever to be elected president unanimously (a feat which he duplicated in the 1792 election). As runner-up with 34 votes (each elector cast two votes), John Adams became vice president. Washington took the oath of office as the first President on April 30, 1789 at Federal Hall in New York City.

The First U.S. Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a large sum in 1789. Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his image as a selfless public servant. At the urging of Congress, however, he ultimately accepted the payment. A dangerous precedent could have been set otherwise, as the founding fathers wanted future presidents to come from a large pool of potential candidates - not just those citizens that could afford to do the work for free.

Washington attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names suggested.

Washington proved an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of talent and character, he held regular cabinet meetings, which debated issues; he then made the final decision and moved on. In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them."

Washington only reluctantly agreed to serve a second term of office as president. He refused to run for a third, establishing the precedent of a maximum of two terms for a president.

LINKS and REFERENCE

A taste for revolutionaries

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|

||||||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2012 NJK. The bird logos and name Solar Navigator are trademarks. All rights reserved. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity working hard for world peace. |

||||||||||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEPLANET | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS | SOLARNAVIGATOR |