|

The

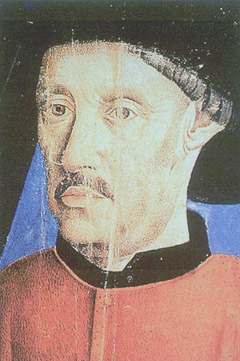

man chiefly responsible for Portugal's age of

exploration was Prince Henry the Navigator, the third

son of King Joao I (John) and his English wife, Queen

Philippa of Lancaster. Henry was born in 1394. As a

youth, he participated in the capture of Ceuta. In 1419,

his father made him governor of Portugal's southernmost

coasts. From 1419 until his death in [1460], Prince

Henry sent expedition after expedition down the west

coast of Africa to outflank the Muslim hold on trade

routes and to establish colonies. These expeditions

moved slowly due to the mariners' belief that waters at

the equator were at the boiling point, that human skin

turned black, and that sea monsters would engulf ships.

It

wasn't until 27 years after Henry's death that Bartolomeu

Dias braved these "dangers" and rounded

the Cape of Good Hope in [1487]. Henry was keenly

interested in and studied navigation and mapmaking. He

established a naval observatory for the teaching of

navigation, astronomy, and cartography about [1450].

Unfortunately, Portugal began slaving operations along

the west coast of Africa. Sailors could offer glass

beads and colored cloth in exchange for tribal captives.

In 1452, Pope Nicolas V

issued his papal bull allowing the enslavement of

"pagans and infidels." Prince Henry's interest

in the slaves was mainly to convert them to

Christianity.

Henry of Portugal, surnamed the

"Navigator", Duke of Viseu, governor of the

Algarve, was born at Oporto on the 4th of March 1394. He

was the third (or, counting children who died in

infancy, the fifth) son of João I, the founder of the

Aviz dynasty, under whom Portugal, victorious against

Castile and against the Moors of Morocco, began to take

a prominent place among European nations; his mother was

Philippa, daughter of John of Gaunt. When Ceuta, the

"African Gibraltar", was taken, in 1413,

Prince Henry performed the most distinguished service of

any Portuguese leader, and received knighthood; he was

now created Duke of Viseu and lord of Covilham, and

about the same time began his explorations, which,

however, limited in their original conception, certainly

developed into a search for a better knowledge of the

western ocean and for a sea-way along the unknown coast

of Africa to the supposed western Nile (now Senegal), to

the rich negro lands beyond the Sahara desert, to the

half-true, half-fabled realm of Prester John, and so

ultimately to the Indies.

Disregarding the traditions which assign 1412 or even

1410 as the commencement of these explorations, it

appears that in 1415, the year of Ceuta, the prince sent

out one John de Trasto on a voyage which brought the

Portuguese to Grand Canary Island. There was no

discovery here, for the whole Canarian archipelago was

now pretty well known to French and Spanish mariners,

especially since the conquest of 1402-06 by French

adventurers under Castilian overlordship; but in 1418

Henry's captain, João Gonçalvez Zarco rediscovered

Porto Santo, and in 1420 Madeira, the chief members of

an island group which had originally been discovered

(probably by Genoese pioneers) before 1351 or perhaps

even before 1339, but had rather faded from Christian

knowledge since.

The story of the rediscovery of Madeira

by the Englishman Robert Machim or Machin, eloping from

Bristol with his lady-love, Anne d'Arfet, in the reign

of King

Edward III (about 1370), has been the subject of

much controversy; in any case it does not affect the

original Italian discovery, nor the first sighting of

Porto Santo by Zarco, who, while exploring the west

African mainland coast, was driven by storms to this

island. In 1424-25 Prince Henry attempted to purchase

the Canaries, and began the colonization of the Madeira

group, both in Madeira itself and in Porto Santo; to aid

this latter movement he procured the famous charters of

1430 and 1433 from the Portuguese crown. In 1427, again,

with the cooperation of his father King João, he seems

to have sent out the royal pilot Diogo de Sevill,

followed in 1431 by Gonçalo Velho Cabral, to explore

the Azores, first mentioned and depicted in a Spanish

treatise of 1345 (the Conosçimiento de todos los

Reynos) and in an Italian map of 1351 (the Laurentian

Portolano, also the first cartographical work to

give us the Madeiras with modern names), but probably

almost unvisited from that time to the advent of Sevill.

This rediscovery of the far western archipelago, and the

expeditions which, even within Prince Henry's life (as

in 1452) pushed still deeper into the Atlantic, seem to

show that the infante was not entirely forgetful of the

possibility of such a western route to Asia as Christopher

Columbus attempted in 1492, only to find America

across his path. Meantime, in 1418, Henry had gone in

person to relieve Ceuta from an attack of Morocco and

Granada Muslims; had accomplished his task, and had

planned, though he did not carry out, a seizure of

Gibraltar. About this time, moreover, it is probable

that he had begun to gather information from the Moors

with regard to the coast of Guinea and the interior of

Africa. In 1419, after his return to Portugal, he was

created governor of the kingdom of Algarve, the

southernmost province of Portugal; and his connection

now appears to have begun with what afterwards became

known as the "Infante's Town" (Villa do

Iffante) at Sagres, close to Cape St. Vincent; where,

before 1438, a Tercena Nobel or naval arsenal

grew up; where, from 1438, after the Tangier expedition,

the prince certainly resided for a great part of his

later life; and where he died in 1460.

In 1433 died King João, exhorting his son not to

abandon those schemes which were now, in the

long-continued failure to round Cape Bojador, ridiculed

by many as costly absurdities and in 1434 one of the

prince's ships, commanded by Gil Eannes, at lengh

doubled the cape. In 1435 Affonso Gonçalvez Baldaya,

the prince's cup-bearer, passed fifty leagues beyond;

and before the close of 1436 the Portuguese had almost

reached Cape Blanco. Plans of further conquest in

Morocco, resulting in 1437 in the disastrous attack upon

Tangier, and followed in 1438 by the death of King

Edward (Duarte) and the domestic troubles of the earlier

minority of Affonso V, now interrupted Atlantic and

African exploration down to 1441, except only in the

Azores. Here rediscovery and colonization both

progressed, as is shown by the royal license of the 2nd

of July 1439, to people "the seven islands" of

the group then known. In 1441 exploration began again in

earnest with the venture of Antam Gonçalvez, who

brought to Portugal the first slaves and gold dust from

the Guinea coasts beyond Bojador; while Nuno Tristam in

the same year pushed on to Cape Blanco.

These successes

produced a great effect; the cause of discovery, now

connected with boundless hopes of profit, became

popular; and many volunteers, especially merchants and

seamen from Lisbon and Lagos, came forward. In 1442 Nuno

Tristam reached the Bay or Bight of Arguim, where the

infante erected a fort in 1448, and where for years the

Portuguese carried on vigorous slave-raiding. Meantime

the prince, who had now, in 1443, been created by King

Henry VI a Knight of the Garter of England,

proceeded with his Sagres buildings, especially the

palace, church and observatory (the first in Portugal)

which formed the nucleus of the "Infante's

Town", and which were certainly commenced soon

after the Tangier fiasco (1437), if not earlier. In

1444-46 there was an immense burst of maritime and

exploring activity; more than 30 ships sailed with

Henry's license to Guinea; and several of their

commanders achieved notable success. Thus Diniz Diaz,

Nuno Tristam, and others reached the Senegal in 1445;

Diaz rounded Cape Verde in the same year; and in 1446

Alvaro Fernandez pushed on almost to the present-day

Sierra Leone, to a point 110 leagues beyond Cape Verde.

This was perhaps the most distant point reached before

1461. In 1444, moreover, the island of St. Michael in

the Azores was sighted (May 8), and in 1445 its

colonization was begun. During this latter year also

John Fernandez spent seven months among the natives of

the Arguim coast, and brought back the first trustworthy

first-hand European account of the Sahara hinterland.

Slave-raiding continued ceaselessly; by 1446 the

Portuguese had carried off nearly a thousand captives

from the newly surveyed coasts; but between this time

and the voyages of Alvise

Cadamosto in 1455-56, the prince altered his policy,

forbade the kidnapping of the natives (which had brought

about fierce reprisals, causing the death of Nuno

Tristam in 1446, and of other pioneers in 1445, 1448,

etc.), and endeavored to promote their peaceful

intercourse with his men. In 1445-46, again, Dom Henry

renewed his earlier attempts (which had failed in

1424-25) to purchase or seize the Canaries for Portugal;

by these he brought his country to the verge of war with

Castile; but the home government refused to support him,

and the project was again abandoned. After 1446 our most

voluminous authority, Azurara, records but little; his

narrative ceases altogether in 1448; one of the latest

expeditions noticed by him is that of a foreigner in the

prince's service, "Vallarte the Dane", which

ended in utter destruction near the Gambia, after

passing Cape Verde in 1448.

After this the chief matters

worth notice in Dom Henry's life are, first, the

progress of discovery and colonization in the Azores -

where Terceira was discovered before 1450, perhaps in

1445, and apparently by a Fleming, called "Jacques

de Bruges" in the prince's charter of the 2nd of

March 1450 (by this charter Jacques receives the

captaincy of this isle as its intending colonizer);

secondly, the rapid progress of civilization in Madeira,

evidenced by its timber trade to Portugal, by its sugar,

corn and honey, and above all by its wine, produced from

the Malvoisie or Malmsey grape, introduced from Crete;

and thirdly, the explorations of Cadamosto and Diogo

Gomez. Of thes the former, in his two voyages of 1455

and 1456, explored part of the courses of the Senegal

and the Gambia, discovered the Cape Verde Islands

(1456), named and mapped more carefully than before a

considerable section of the African littoral beyond Cape

Verde, and gave much new information on the trade routes

of northwest Africa and on the native races; while

Gomez, in his first important venture (after 1448 and

before 1458), though not accomplishing the full Indian

purpose of his voyage (he took a native interpreter with

him for use "in the event of reaching India"),

explored and observed in the Gambia valley and along the

adjacent coasts with fully as much care and profit. As a

result of these expeditions the infante seems to have

sent out in 1458 a mission to convert the Gambia negroes.

Gomez' second voyage, resulting in another

"discovery" of the Cape Verde Islands, was

probably in 1462, after the death of Prince Henry; it is

likely that among the infante's last occupations were

the necessary measures for the equipment and despatch of

this venture, as well as of Pedro de Sintra's important

expedition of 1461.

The infante's share in home politics was

considerable, especially in the years of Affonso V's

minority (1438, etc.) when he helped to make his elder

brother Pedro regent, reconciled him with the

queen-mother, and worked together with them both in a

council of regency. But when Dom Pedro rose in revolt

(1447), Henry stood by the king and allowed his brother

to be crushed. In the Morocco campaigns of his last

years, especially at the capture of Alcazar the Little

(1458), he restored the military fame which he had

founded at Ceuta and compromised at Tangier, and which

brought him invitations from the pope, the emperor and

the kings of Castile and England, to take command of

their armies. The prince was also grand master of the

Order of Christ, the successor of the Templars in

Portugal; and most of his Atlantic and African

expeditions sailed under the flag of his order, whose

revenues were at the service of his explorations, in

whose name he asked and obtained the official

recognition of Pope Eugenius IV for his work, and on

which he bestowed many privileges in the newly-won lands

-- the tithes of St. Michael in the Azores and one-half

of its sugar revenues, the tithe of all merchandise from

Guinea, the ecclesiastical dues of Madeira, etc. As

"protector of Portuguese studies", Dom Henry

is credited with having founded a professorship of

theology, and perhaps also chairs of mathematics and

medicine, in Lisbon -- where also, in 1431, he is said

to have provided house-room for the university teachers

and students.

To instruct his captains, pilots and other

pioneers more fully in the art of navigation and the

making of maps and instruments he procured, says Barros,

the aid of one Master Jacome from Majorca, together with

that of certain Arab and Jewish mathematicians. We hear

also of one Master Peter, who inscribed and illuminated

maps for the infante; the mathematician Pedro Nunes

declares that the prince's mariners were well taught and

provided with instruments and rules of astronomy and

geometry "which all mapmakers should know";

Cadamosto tells us that the Portuguese caravels in his

day were the best sailing ships afloat; while, from

several matters recorded by Henry's biographers, it is

clear that he devoted great attention to the study of

earlier charts and of any available information he could

gain upon the trade routes of northwest Africa. Thus we

find an Oran merchant corresponding with him about

events happening in the negro-world of the Gambia basin

in 1458. Even if there were never a formal

"geographical school" at Sagres, or elsewhere

in Portugal, founded by Prince Henry, it appears certain

that his court was the center of active and useful

geographical study, as well as the source of the best

practical exploration of the time.

The prince died on the 13th of November 1460, in his

town near Cape St. Vincent, and was buried in the church

of St. Mary in Lagos, but a year later his body was

removed to the superb monastery of Batalha. His

great-nephew, King Dom Manuel had a statue of him placed

over the center column of the side gate of the church of

Belem. On the 24th of July 1840, a monument was erected

to him at Sagres at the instance of the Marquis de Sá

da Bandeira.

The glory attaching to the name of Prince Henry does

not rest merely on the achievements effected during his

own lifetime, but on the subsequent results to which his

genius and perseverance had lent the primary

inspiration. To him the human race is indebted, in large

measure, for the maritime exploration, within one

century (1420-1522), of more than half the globe, and

especially of the great waterways from Europe to Asia

both by east and by west. His own life only sufficed for

the accomplishment of a small portion of his task. The

complete opening out of the African or southeast route

to the Indies needed nearly forty years of somewhat

intermittent labor after his death (1460-98), and the

prince's share has often been forgotten in that of

pioneers who were really his executors -- Diogo Cam,

Bartholomew Diaz or Vasco

da Gama. Less directly, other sides of his activity

may be considered as fulfilled by the Portuguese

penetration of inland Africa, especially of Abyssinia,

the land of the "Prester John" for whom Dom

Henry sought, and even by the finding of a western route

to Asia through the discoveries of Columbus, Vasco

Nuñez de Balboa and Ferdinand

Magellan.

Born:

4-Mar-1394

Birthplace: Oporto, Portugal

Died: 13-Nov-1460

Location of death: Vila do Infante, Portugal

Cause of death: unspecified

Gender: Male

Ethnicity: White

Sexual orientation: Straight

Occupation: Royalty

Nationality: Portugal

Executive summary: Spurred European global

exploration

Father: João I (King of Portugal)

Mother: Philippa of Lancaster (dau. of John

of Gaunt)

Solar

Cola sponsor this website

|