|

THE BOUNTY and PITCAIRN ISLAND

|

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT |

|

HMS Bounty sailed from Spithead, England on December 23, 1787 with Captain William Bligh and a crew of 45 men bound for Tahiti. Their mission was to collect breadfruit plants to be transplanted in the West Indies as cheap food for the slaves.

There was a lot happening in the world in 1789. The Constitution of the United States of America was ratified. The French Revolution occurred. In England, King George III was influenced by the members of the Royal Society in their quest for scientific and economic expansion, and the King had authorized the Bounty expedition. The mutiny onboard HMS Bounty happened in the remote South Pacific.

Life in the Royal Navy was harsh. The majority of crewmembers of each ship were pressed into service by "Press Gangs." They were forced onto the ship and then not allowed to leave, sometimes for years at a time. A vital statistic in the story of HMS Bounty is that every person in the crew was a volunteer.

CAPTAIN WILLIAM BLIGH

William Bligh, the Captain of the expedition, was born September 9, 1754. He was heavily built and below average in height, with black hair, blue eyes and a pale complexion. He gained a reputation in the Royal Navy for having a volatile temper and he used foul language when angered. Bligh went to sea at the age of sixteen as an able bodied seaman and not a midshipman. Seven months after he entered the service, he was given his warrant as a midshipman and then he made his way through the officer ranks.

When the famous explorer Captain James Cook was preparing to go to the Pacific for his third voyage, in HMS Resolution, Bligh was designated as his navigator. Bligh at the time was twenty-three and a warrant officer not yet carrying the King’s commission. Bligh received high praise from Captain Cook. Bligh’s charts surveys and records were impeccable and some are still used today because of their accuracy. When Cook was killed in Hawaii, Bligh navigated HMS Resolution back to England.

Bligh then served with distinction in the Fleet during the war with France. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1781. Also in 1781 he married Elizabeth Betham and was appointed as Master of HMS Cambridge. Onboard HMS Cambridge, Bligh became acquainted with Fletcher Christian. In his diary, Christian claimed that Bligh “treated him like a brother.” Bligh taught Christian the use of the sextant and frequently dined with him.

With the advent of peace in 1783, England reduced the size of the Navy and Bligh was reduced to half pay. Through his wife’s family he was appointed as Commander of the merchant ship Britannia and sailed between England and the West Indies. Among his crew was his friend Fletcher Christian. In 1787, while he was still away, he was appointed to command HMS Bounty for the voyage to Tahiti and the West Indies. It is interesting to note that he would be earning much less in the Royal Navy than in the Merchant Navy. Bligh was the only commissioned officer on HMS Bounty, but he was not appointed to Captain. Bligh understood that he would be promoted to Captain upon successful completion of the voyage.

FLETCHER CHRISTIAN

Fletcher Christian was born in Cumberland on September 15, 1764 of a well to do family. He went to sea at the age of sixteen, and two years later he sailed aboard HMS Cambridge where he met William Bligh for the first time. Christian was about five feet nine inches tall with a dark complexion and well muscled. He was sometimes described as swashbuckling, a slack disciplinarian, a great favorite with the ladies, conceited but also mild, generous, open and humane. In describing the mutineers, Bligh described Christian as “master’s mate, aged twenty-four years, five feet nine inches high, blackish, or very dark brown complexion, dark brown hair, strong made, a star tattooed on his left breast, tattooed on his backside; his knees stand a little out, and he may be called rather bow-legged. He is subject to violent perspirations, and particularly in his hands, so that he soils anything he handles.”

THE MISSION: CHEAP FOOD FOR PLANTATIONS

The planters of the West Indies had for years been looking for a cheap way to feed their slaves. The Royal Society petitioned King George III to send an expedition to the South Seas to bring back for transplantation the easily grown breadfruit plant. The King had his scientific advisor, Sir Joseph Banks, make the arrangements. Sir Joseph had sailed to the South Pacific with Captain Cook and had a first hand knowledge of the breadfruit plant. He had eaten and enjoyed the breadfruit. Sir Joseph Banks was a botanist, and he employed the person he considered best suited for this voyage’s botanist, David Nelson. They were well acquainted and had served together in Tahiti. An assistant, William Brown, was hired to help Nelson. Sir Joseph Banks also knew William Bligh through their association with Captain Cook, and Banks recommended Bligh to head the expedition because of his navigational skills.

A SHIP FOR THE MISSION

The collier ship Bethia was converted for the voyage and renamed HMS Bounty. (There is a sailor’s tradition that it is bad luck to change the name of a ship.) Very technically, the ship was named HMAV (His Majesty’s Armed Vessel) Bounty. The ship carried four four-pounders and ten swivels. The ship was 215 tons, ninety feet ten inches on deck, with a beam of twenty-four feet three inches. From the beginning Bligh considered the ship too small for the mission. He had the masts shortened and the ballast reduced to support the ship. The great cabin and other spaces were taken over for the transportation of the breadfruit, and part of the decks were lined with lead to collect fresh water for the plants. The result was an overcrowding of the ship, which left even less room for the officers and crew.

Bounty quarterdeck

A CREW FOR THE MISSION

Some of Bligh’s former shipmates asked to join him on this voyage. Along with Christian he had Lawrence LeBogue, the sailmaker; John Norton, the quartermaster; David Nelson, the botanist; and William Peckover, the gunner. Christian applied for the appointment as Master, but John Fryer had been appointed by the Admiralty. Bligh had his friend appointed as Master’s Mate in addition to William Elphinstone. The Admiralty also appointed John Huggen as Surgeon, obviously not knowing he was a drunk. Thomas Denman Ledward was the Surgeon’s Mate.

There were five warrant officers onboard and no marines. The Master-at-Arms, Charles Churchill, was one of Bligh’s biggest problems, and of no help. The crew was relatively young, several only fourteen and the oldest was thirty-nine. Bligh had been ready to sail for weeks but was held up by the Admiralty. Finally his orders came to go to Tahiti via Cape Horn. He asked for and received discretionary orders to proceed via the Cape of Good Hope.

THE OUTWARD VOYAGE

On

December 23, 1787 HMS Bounty sailed from Spithead for

Tahiti via Cape Horn. There

were 46 volunteers onboard. Bligh

split the crew into three watches instead of the usual

two. This

was considered a kindly gesture and made life aboard

more restful and healthy.

Bligh

appointed Fletcher Christian acting Lieutenant and

second in command over Fryer. Bligh had learned from Captain Cook that the well being of the crew is of paramount importance in the success of any mission. He knew that sauerkraut would prevent the dreaded scurvy and it was always on the menu. He knew that exercise was important for the crew’s well being, and he brought along an almost blind fiddler, Michael Byrne, to play music and lead the dancing. Seaman James Valentine died on the outbound voyage from a fall, and from totally inadequate care by the surgeon. One punishment was recorded. Fryer reported Matthew Quintal for insolence and Bligh ordered twenty lashes. (Thirty-six were the norm in the Navy for this offence.)

When the ship approached Cape Horn it was impossible to get through to the Pacific Ocean. Bligh and the crew of Bounty tried for thirty days, fighting terrible storms with at least hurricane force winds, snow and rain with very high seas. To Bligh’s credit he did not lose a man or a spar or a yard of canvas. Bligh was still using the Great Cabin at that time, and he opened it for the use of the crew during those bad days. That was considered as kindly and unusual for a captain to do at that time. They were at last forced to turn east for the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. Bligh addressed the crew and thanked them for their valiant effort. They landed at False Cape, stayed there thirty-eight days, and refitted the ship. Finally they arrived in Tahiti on October 26, 1788.

This was Bligh’s second visit to Tahiti and he had many friends on the island. The Bounty stayed in Tahiti nearly six months in a luxury most of the crew could never imagine. They were never cold or hungry. The beautiful flora were only surpassed by the women of the island, and it was considered a paradise.

The reasons for the long stay in Tahiti were completely rational: (1) They had been delayed in leaving England; (2) They had to collect their plants in the proper season in order for them to survive; and (3) They had to wait for the proper winds to take them home.

Bligh has been criticized for his leadership role while the ship was in Tahiti. While his log and observations of the island and people were meticulous, he was too slack and his men knew it. When he delegated responsibilities to his subordinates, he did not check to make sure that his orders were followed. Examples of this led to the sails being allowed to rot and an anchor line was cut. Bligh also never took the ship underway for short cruises to keep the crew sharp. The chronometer also stopped because he left the ship himself to look for deserters and gave no one the responsibility to check the chronometer.

On January 5, 1789 William Muspratt, John Millward and Charles Churchill stole a ship’s boat and some muskets and deserted. Midshipman Thomas Hayward was Officer of the Watch and he was asleep when this happened. Bligh had Hayward confined in irons and then Bligh set off to find the deserters. It took three weeks but he found them. Churchill got 12 lashes, and Muspratt and Millward each got 24 lashes. (The normal punishment would have been hanging after the flogging.)

Bligh made Christian commander of the shore party to collect the breadfruit plants. Living arrangements were set up ashore and there is conflicting evidence as to all the many relationships that were developed with the Tahitian women. When the Bounty eventually left with the breadfruit, many crewmembers left behind strong attachments.

HMS Bounty sets sail

THE RETURN VOYAGE

When HMS Bounty finally left Tahiti on April 6, 1789 there were 1015 breadfruit plants onboard, and a very unhappy crew. They were back to the harsh realities of shipboard life. Bligh’s reaction was ranting and raving. The crew and the officers reacted with disgruntled compliance. Christian was affected the most and seemed to be the recipient of most of Bligh’s abuse. Bligh berated Christian during the day, and invited him to dine in the evening. Christian decided to desert. Right up until the mutiny, Bligh never had a clue that he and Christian were not still friends.

After about three weeks of sailing, Christian confided to Midshipman Edward Young his plan to build a raft and sail away. Young pointed out there were sharks in the water that would make it certain death. It was probably Young who suggested that Christian should take the ship and do away with Captain Bligh. Christian put the idea to Quintal, William McCoy, Alexander Smith, Charles Thompson, Williams and Burkitt. These were all seamen. They then tried to recruit three midshipmen, Stewart, Hayward and Hallet, but they refused and were confined below decks. Christian then broke into the arms chest and took the ship.

MUTINY MR CHRISTIAN

In the early morning of April 28, 1789 Bligh was awakened and brought out on deck in his night shirt, and with his hands tied, was held abaft the mizzenmast. When the crew was asked who wanted to leave with Bligh thirty men volunteered. Bligh made several last pleas pointing out that “ I have a wife and four children in England, and you have danced my children on your knee.” Christian’s answer was, “It is too late Captain Bligh, I have been forced through hell these past three weeks.” The mutiny was described as a very confused event, filled with threats and counter-threats. Some of the men who wanted to go with Bligh were forced to stay with the Bounty because of the lack of space in the boat. No person was killed or physically injured.

Captain Bligh and 18 men were cast adrift in the South Pacific Ocean in a 23 foot boat. The people in the boat with Bligh were: John Fryer, William Elphinstone, William Cole, William Peckover, William Purcell, Thomas Denman Ledward, Thomas Hayward, John Hallet, Peter Linkletter, John Norton, George Simpson, Thomas Hall, Robert Lamb, David Nelson, Lawrence LeBogue, John Samuel, John Smith, and Robert Tinkler.

Bligh then proceeded to make one of the most heroic voyages in history. First they made to the nearby island of Tofoa. The natives were hostile and they were lucky to get away with only the loss of John Norton, who was a hero in allowing the boat to escape. Then there were eighteen men with enough food and water for five days. Bligh made the decision to sail to Kupang and to reapportion the food to serve for 50 days. They eventually made the heroic voyage in 48 days, landing in Timor on June 12, 1789. No one died on the voyage, however three men died in Batavia. Bligh’s Clerk, John Samuel, saved the Log and Bligh’s journals and Bligh was grateful to him for his loyal actions.

After Bligh arrived back in England on March 14, 1790 he was court-martialed and acquitted. Shortly thereafter Bligh published his “Narrative of the Mutiny on Board His Majesty’s Ship ‘Bounty’.” It was followed 2 years later by a more complete version, describing the entire ‘Voyage.’ These books were among the first of over 250 books that have described some aspect of the adventure and its consequences.

SEARCH FOR THE MUTINEERS

Captain Edward Edwards was given the assignment to take HMS Pandora to Tahiti and find the Bounty mutineers. Two Bounty midshipmen, Thomas Hayward and John Hallet, were also assigned to that mission to identify members of the crew. By the time Pandora arrived in Tahiti on March 23, 1791 there were only fourteen Bounty crewmembers there. Churchill and Thompson had been murdered. Eight crewmembers gave themselves up immediately and others took off to the mountains only to be caught and brought back to Pandora in irons. All of the Bounty crewmembers were put into a cage on the main deck called “Pandora’s Box.” Pandora struck a reef near Australia on August 28, 1791. Ten of the fourteen Bounty crewmen escaped with the Pandora crew, and four drowned in their chains. Four boats got away from the Pandora wreck and arrived at Timor, 1000 miles away, on September 16, 1791.

COURT MARTIAL

The surviving Bounty crewmen from the Pandora were tried by court martial in England starting on August 12, 1792. Thomas Ellison, John Millward and Thomas Burkitt were found guilty of mutiny and hanged at Spithead onboard HMS Brunswick on October 29, 1792. Others were declared innocent of mutiny and released, and two notables, James Morrison and Peter Heywood, were pardoned.

William Bligh was promoted to Captain, given command of HMS Providence and with the escort vessel Assistant, was dispatched to Tahiti for another breadfruit mission. This mission was successful in that the breadfruit was transplanted in the West Indies, and the ships returned safely to England. However, the slaves hated the breadfruit, and refused to eat it. Bligh was involved in three mutinies. After the Bounty, there was the Fleet Mutiny at the Nore, and then the mutiny while he was Governor of New South Wales in Australia in 1805. He died with the rank of Vice-Admiral of the Blue at the age of 64 on December 7, 1817. He is buried at St. Mary’s at Lambeth Churchyard and Garden in London.

MUTINEERS SEARCH FOR SAFE HAVEN

After the mutiny, the Bounty first returned to Tahiti. Christian was elected captain, and the ship set off to find a place to live. The mutineers started, then abandoned a settlement on the island of Tubuai, and the ship again returned to Tahiti. Nine of the Bounty mutineers with six Polynesian men, twelve women and one baby left Tahiti onboard Bounty. They searched for and found, Pitcairn Island, which had been incorrectly charted years before. They found the island on January 15, 1790. After they took everything of value off the ship, HMS Bounty was burned on January 23, 1790 and the mutineers set up life on Pitcairn.

Pitcairn Island

The mutineers who settled on Pitcairn Island were Fletcher Christian, Edward Young, John Mills, William Brown, Isaac Martin, William McCoy, Matthew Quintal, John Williams and John Adams (at that time known as Alexander Smith). The Polynesian men who settled with the mutineers were: Taroamiva, Uhuu, Minarii, Teimua, Niau, and Tararo. The Tahitian women were: Mauatua, Teraura, Tevarua, Teio, Tehuteatuaonoa, Toowhaiti, Vahineatua, Fahoutu, Tetuahitea, Mareva, Tinafoonia, Obuarei, and the baby Sarah.

The little colony was not a happy one, in great measure due to the inequality between the British mutineers and the Polynesian men regarding sharing the women and the land. The mutineers had plenty of female companionship and the Polynesians very little, and dissention, then murder were the result. On September 20, 1793 five of the whites, including Christian, and all of the Polynesian men were killed. Most of the remaining mutineers died or were killed by the Tahitian women, especially after a method to make spirits was discovered. Only Adams and Ned Young remained. Ned Young died of asthma in 1800.

John Adams, (who signed onboard Bounty hiding from the law as Alexander Smith), was the only male survivor. He had been a violent person, but had changed dramatically. Midshipman Young had taught him to read and the Bible became his saving grace. He went on to become the respected leader on Pitcairn, and died on March 5, 1829, forty years after the mutiny. The island colony was first visited in 1808 by Captain Mayhew Folger in the American sealer Topaz. Adams gave Folger a copy of the Log, along with the Bounty’s chronometer, as proof of the colony’s existence. The Admiralty took no action regarding the report from Topaz. Pitcairn was next visited by two British men of war (Captains’ Staines and Pipon in Briton and Tagus) in 1814. Staines reported to the Admiralty that, after he and Pipon had studied the circumstances on the island, to take John Adams back to England to stand trial for the mutiny would be “an act of great cruelty and inhumanity.”

The Log of the Bounty is in the British National Maritime Museum, and the Bounty’s chronometer (K2) is in the Royal Observatory, also in Greenwich, England.

PITCAIRN ISLAND

Pitcairn Island became and is a part of the British Empire. In 1831, the people were very briefly moved to Tahiti. The experience was a failure, and the people quickly returned to Pitcairn. In 1856, the population had become overcrowded, and all of the people were moved to Norfolk Island. Very soon thereafter many moved back to Pitcairn. Since then the fortunes of the Pitcairn people have ebbed and flowed, depending upon each other, the weather, the passing of ships, the sale of postal stamps, and the sale of island made products. The descendents of the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian wives still live on Pitcairn Island, with remnants of the original ship, in addition to their descendents on Norfolk Island, and all around the world. January 23 is celebrated each year on Pitcairn Island as ‘Bounty Day.’

LINKS TO OTHER BOUNTY SITES

Today's Bounty Other REFERENCES TO HMS BOUNTY or MUTINEERS

GENERAL HISTORY LINKS

MARITIME HISTORY

HMS BOUNTY | MEL GIBSON | MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

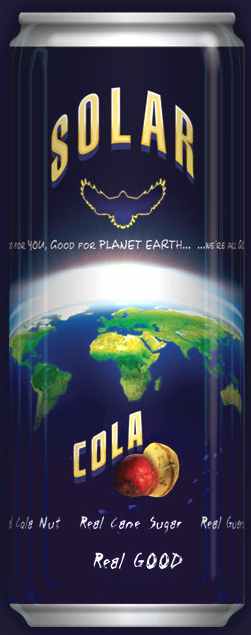

....... The World in Your Hands

330ml alu Earth Can

|

|

This

website is Copyright © 1999 & 2007

Solar Cola Ltd. The bird logo |

| AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEBIRD | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS |