|

Sir

Richard Branson isn’t just a guy with a beard and a

penchant for sweaters, balloons and boat racing.

He’s also the man behind one of the most successful

brands in the world: Virgin. But then you probably knew

that already.

Richard

Branson is synonymous with Virgin – and this isn’t

an accident: “If you get your face and your name

out there enough, people will start to recognise you.

Many people know the Virgin brand better than the names

of the individual companies within the group. A young

girl once came up to me and told me I could be famous

because I looked just like Richard Branson. Branding is

everything.”

Of

course, there’s more to Richard Branson than Virgin,

although for most people this would probably be enough.

But then, Richard Branson is not most people. He’s a

man who likes a challenge, whether it’s in business or

pleasure. On top of being knighted for ‘services to

entrepreneurship’, he has been involved in a number of

world-record breaking attempts.

“My

first success was in 1986 with my boat “Virgin

Atlantic Challenger II”. I wanted to rekindle the

spirit of the Blue Riband by crossing the Atlantic Ocean

in the fastest ever recorded time.” A year

later, he crossed the same ocean, this time in a hot air

balloon. The "Virgin Atlantic Flyer" was not

only the first hot-air balloon to cross the Atlantic but

was also the largest balloon ever at 2.3 million cubic

feet.

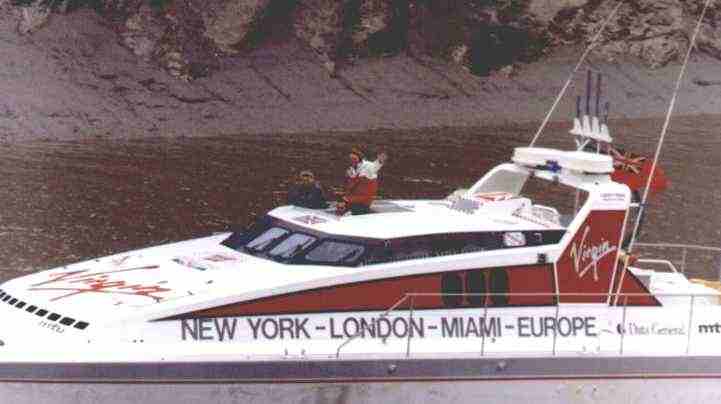

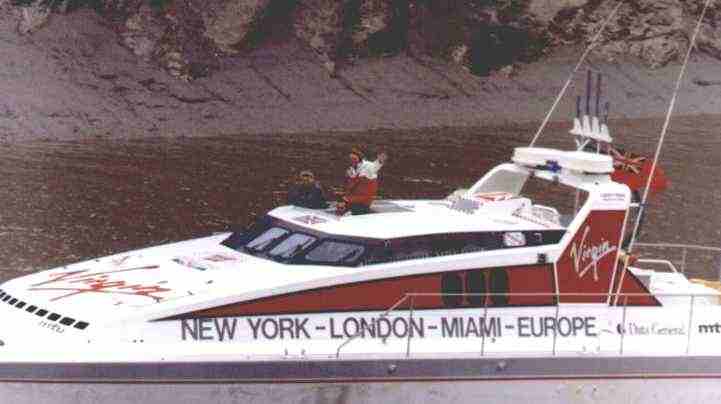

Virgin

Atlantic Challenger II being re-fuelled 10 miles off

Halifax in 1986

The

Blue Riband was established by shipping magnates in 1838

as an informal competition. Richard Branson broke

the record, but the Hales' trustees refused to award him

the trophy because his boat did not have a commercial

maritime purpose and he had stopped to refuel.

The

SS United States' record was not broken until 1990, when

the 74m (243ft) catamaran Hoverspeed Great Britain

completed the crossing with an average speed of 36.65

knots. In 1987 Mr Branson abandoned the sea and

took to the air. His Virgin Atlantic Flyer hot air

balloon was the first to cross the Atlantic that year,

and in 1991, he broke the Pacific record by crossing

from Japan to Arctic Canada.

Richard

Branson's first attempt to cross the Atlantic in 1985

followed the launch of his Virgin Atlantic

airline. The voyage was a failure, his boat

sinking off Land's End, but his second attempt the

following year brought him recognition and publicity.

But

he was denied the Blue Riband by the trustees of the

award because he had broken two rules of the competition

- he had stopped to refuel and his vessel did not have a

commercial maritime purpose. The SS United States'

record was not broken until 1990, when the 74m catamaran

Hoverspeed Great Britain completed the crossing with an

average speed of 36.65 knots.

Length

over all - 72 feet Hull - Aluminum

26

June 1986: Branson on course for Blue Riband

Entrepreneur

Richard Branson set off on his second attempt on the

26th June 1986 to claim the transatlantic crossing

record for Britain. Mr Branson and his team left

New York at dawn on their 72 ft powerboat Virgin

Challenger II for the 3,000 mile (4,828 km)

voyage. If they reach Bishop's Rock, off the Isles

of Scilly, by 2100 BST on 29 June they will recapture

the Blue Riband for the UK - held by liner SS United

States since 1952 for a crossing in three days and 10

hours.

The

millionaire businessmen tried to break the record last

year, but his boat sank just 138 miles (222 km) from the

British coast. Mr Branson told the BBC he was

confident they would succeed this year. "The

boat's ready, the crew are ready and the weather

forecast is reasonable - hopefully we'll be there for

Sunday lunch," he said.

A

spokesman at the Virgin Challenger London headquarters

said the team had almost reached Nova Scotia for the

first of three refuelling stops at 2100 BST and was two

hours ahead of schedule. After taking on more

fuel, the £1.5m boat will head across the ocean on the

"great circle" route - the quickest course

across the Atlantic.

BBC

Tomorrow's World presenter Peter Macann is on the

Challenger and said conditions had been perfect for the

first stage of the voyage. "The only point of

excitement was when I was driving and a whale surfaced

about 50 m (164 ft) from the boat - I just managed to

swerve to avoid it," he said.

29

June 1986: Branson beats Atlantic speed record

Millionaire

Richard Branson today smashed the world record for the

fastest crossing of the Atlantic. His 72-ft powerboat,

the Virgin Atlantic Challenger, reached the Bishop Rock

off the Isles of Scilly just after 1930BST. Mr

Branson completed the voyage more than two hours faster

than the previous record-holder, the SS United States,

which has held the title since 1952. The

Challenger's successful crossing came in spite of

problems with the fuel system.

Her

voyage was closely monitored from an operation room in

London, where tension mounted as the £1.5m powerboat

headed for the finishing line at more than 50 knots. Mr

Branson's voice was relayed over the radio, keeping the

team up-to-date on his progress.

It

took the Challenger one hour from the finishing line to

reach the island of St Mary's, where crowds were waiting

in their hundreds in spite of the pouring rain.

After three days at sea, Branson, the head of a

multi-million-pound airline and record empire, arrived

triumphant - before being pushed into the Atlantic by

his crew for a joke.

In

London the champagne flowed, but it is still not certain

whether the team will be able to claim the Blue Riband,

the trophy awarded to the American boat in 1952.

The prize currently resides in a New York maritime

museum, and the final decision on the Challenger's claim

appears to lie with the museum and trustees of the

trophy.

| |

|

|

Virgin

Atlantic Challenger II - Richard Branson waving

THE

AGA KHAN - TACKLES VIRGIN CHALLENGER RECORD

Destriero

is the ultimate big boy's toy, with 54,000bhp and sexy

Italian styling. Next month it will attempt to snatch

the Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic voyage.

Corporate sponsors' names decorate its deck; but who

owns it?

It's

all Richard Branson's fault. The record for the

fastest sea crossing of the Atlantic, the Blue Riband,

had been held for more than 30 years by the SS United

States, the last of the great high-speed liners. The

liner itself lay mothballed in the harbour at Norfolk,

Virginia; its owners had gone out of business; and the

Hales Trophy which it won was gathering dust in the

American Merchant Maritime Museum. Despite one

American team's attempts on the record in the

Seventies, interest in the fastest transatlantic ship

had dwindled. Nobody cared because everybody flew.

But

Branson wanted everybody to fly on his new airline,

Virgin Atlantic. So in 1985 he set out to take the

Blue Riband in the Virgin Atlantic Challenger

powerboat and to generate publicity for the airline.

He failed in the first objective (the boat sank 138

miles off Land's End) but succeeded magnificently in

the second, with the result that a queue of contenders

for the Blue Riband began to form. Branson tried again

(this time successfully), and was followed by the

American millionaire Tom Gentry, who also had two

attempts; Hoverspeed's Sea Cat made the crossing,

Italy's Azimut Atlantic Challenger failed to do so,

and earlier this month the French boat, Jet Ruban

Bleu, turned up in New York for its second attempt.

And as the contenders multiplied, so did the prizes:

there are now four different trophies for the fastest

Atlantic crossing.

The

most powerful challenge for the Blue Riband since its

revival will come from the Italian vessel Destriero,

which next month aims to take all four trophies by

breaking the record in both directions across the

Atlantic. The power does not come merely from its

54,000bhp engines. Behind Destriero's challenge are

the Aga Khan, Fiat's Giovanni Agnelli and the

presidents of Italy's state-owned industrial holding

company, IRI, and its Olympic committee. The all-white

boat is decorated with the logos of Fiat, the petro-chemical

giant Agip, Ciga Hotels and the Meridiana airline

(both controlled by the Aga Khan), and the

nationalised shipyard, Fincantieri, which built

Destriero. Together with other sponsors they have

invested $12 million in the challenge -- and that

excludes the cost of the vessel.

For

the last month Destriero has been undergoing trials at

its home port of Porto Cervo on Sardinia's Costa

Smeralda, the holiday resort developed by the Aga

Khan. Moored initially near the clubhouse of the Yacht

Club Costa Smeralda (president: the Aga Khan), under

whose flag it has entered the Atlantic challenge, the

67-metre, 400-ton vessel dominated the small bay.

Early-season holiday-makers gathered on the quayside

to look at it, buzzed around on jet-skis and in

dinghies, bought spin-off merchandise with the

Destriero badge (polo shirt L40, wind-cheater L75) or

simply gazed across the bay at the high-tech

apparition. "Look at that yacht," said an

astonished young girl as she caught her first sight of

it. "That's not a yacht, it's a ship,"

replied one of her friends scornfully.

They

were both right. Cesare Fiorio, the 52-year-old former

sporting director of the Ferrari Grand Prix team who

has masterminded the Destriero challenge, takes pains

to distinguish it from the other challengers of the

Branson generation: "It's not a powerboat, it's a

sea-going ship". But the brass plaque issued by

Det Norske Veritas, which classifies vessels for

insurance purposes, describes it as a "Gas

Turbine Yacht". Destriero calls itself "a

steed or war horse" (the English translation of

the name), but anybody who thought it was an aeroplane

wouldn't be far from the truth: it has three General

Electric aero engines, while an FA-18 Hornet jet

fighter gets by with only two.

One

could just hear the rising whine of the turbines up on

the bridge, set high in a superstructure styled by

Pininfarina, Ferrari's designer, as Destriero was

towed out of the marine by a tug. But the loudest

noise was the hum of the computers. A total of 16

screens display information from the two on-board

computer systems. One of them controls the engines and

the three water-jets; the other is for navigation, and

is so sophisticated that it not only guides the vessel

along a predetermined transatlantic route but also

warns of obstacles like ships and buoys (the former at

a distance of 96 miles) and even suggests ways of

avoiding a collision.

On

a short trip along the Sardinian coastline, the

closest we got to a collision was with the tug, which

radioed Destriero to slow down until it had got out of

the way. Thereafter, all was peace and quiet: on an

almost completely flat sea, Destriero accelerated to

59 knots -- just short of its maximum speed but still

almost 70mph -- with about as much drama as an

Intercity train leaving Euston. Down below, fuel was

being sucked out of the 740-ton tank and into the

turbines at the rate of 8000 litres per hour; but up

on the bridge most of the 14-man crew in their

corporate sport outfits just wandered from one

suede-look chair to another, and the rest of us

watched the sea slide past and wondered why

cross-channel ferries make such a fuss about doing 22

knots.

The

technology of Destriero is not new - its aluminium

hull, gas turbines and integrated navigation system

are already familiar marine features -- but it is

being tested beyond the known limits because, as

Fiorio says, "nobody has ever done 65 knots in a

67-metre vessel before". He is confident that

"although sea navigation has not developed to the

same extent as cars and aeroplane in the last 50

years, Destriero's philosophy will be adopted for

high-speed, 45-knot ships in the near future".

The Fincantieri shipyard has, Fiorio says, already

designed a ferry for the Sardinian crossing which

would be capable of that speed while carrying 400

passengers and 150 cars. He is equally confident that,

barring misfortune or very bad weather, Destriero will

break the records, both on the crossing from Gibraltar

to New York and the more familiar, shorter voyage back

to the Scilly Isles. "The first 10 to 15 hours

will be critical: with a full fuel load, the vessel

floats much lower in the water, and in bad weather the

waves break right across it".

But

whether Destriero will take all the available prizes

is a matter for lawyers rather than mariners. The

Virgin Atlantic, Daily Mail and Columbus Atlantic

trophies (for, respectively, the fastest crossing, the

fastest crossing without refuelling, and the fastest

return crossing, again without refuelling) pose no

problem. Nor does the Blue Riband, which was never a

formal competition and therefore has no rules and no

trophy. The difficulty lies with the Hales Trophy,

first presented in 1935 by Harold Keats Hales, MP for

Hanley. The premier award for the transatlantic

crossing and now commonly regarded as the symbol of

the Blue Riband, it is currently held by the

Hoverspeed Great Britain Sea Cat with a time of 79

hours and 54 minutes; it was not given to the Branson

generation of powerboats (although Tom Gentry's

fastest-ever crossing took 17 hours less than the Sea

Cat) on the grounds that specially-built vessels which

had to be refuelled en route were not in keeping with

the spirit of the trophy, which was originally

intended for high-speed liners.

"For

Destriero" says Fiorio, "the problem is the

requirement that the Hales Trophy can only be awarded

to a ship which ultimately has a commercial use: it

must be operated by a sea transportation company to

carry passengers or freight. The trustees asked us to

make a declaration that Destriero would have a

commercial use; if we didn't, we would not get the

trophy".

In

early May, Fiorio had still not decided what to do.

"It's not up to us what happens to the vessel

afterwards, it's up to the owners. And we don't know

what they want to do with it". So who are the

owners of the Destriero, valued by some people at $50

million? Fiorio wasn't saying: "We don't know, we

just run the ship", he replied with a smile and

shrug that made it clear that anybody who did want to

know would have to find out for themselves.

Surreptitious

questioning elsewhere led to a tip that the ship was

controlled by an Irish company called Bravo Romeo.

(The name is the call sign for the letters 'B' and 'R'

which presumably stand for Blue Riband.) A company

search revealed that 99 per cent of its shares are

held by a Swiss-based company, and the two American

designers of Destriero are among its directors.

Connections with a familiar name began to crop up. The

remaining 1 per cent of the shares are held by a

senior official in the secretariat of the Aga Khan;

the third director, a lawyer, is also a director of a

British company associated with the Aga Khan.; the

Notes to the Financial Statements record that in the

year ended November 1989, the company owed $1,282,715

on a loan account to...the Aga Khan.

Finding

out what the owners of Destriero propose to do with it

after the attempt on the Blue Riband shouldn't be too

difficult for Fiorio. He probably only has to pop into

the yacht club and ask its president.

Richard

Branson's Open Letter (and picture!) to Qantas CEO

Geoff Dixon

Sir

Richard Branson is a genius at scoring public

relations coups.

His

open letter to Geoff Dixon creates a spectacular

'win-win' for Branson (and perhaps a lose-lose for

Dixon!).

Whatever

now happens, the certain result is that Branson will

earn substantial more publicity for himself and his

airline, in the 'underdog' role that he portrays so

well.

|

Flamboyant

Sir Richard Branson founded Virgin Atlantic

Airways in 1984. In 2000, he started a

new airline in Australia - Virgin Blue.

At

the time of Virgin Blue's conception, there

was a fair measure of skepticism within

Australia as to whether it would be possible

for what would have become a third Australian

airline to survive. Several earlier

attempts by other would be competitors to the

two established airlines (Qantas and Ansett)

had all ended in ignominious failure. Of

course, Qantas did all it could to discourage

and disparage its new competitor.

Nonetheless,

Virgin Blue proceeded, and then, more or less

fortuitously perhaps, Ansett (owned by Air New

Zealand) went bankrupt, and Virgin Blue

suddenly found a market that was reasonably

full of air service change to a market where

40% of all flights had suddenly ceased.

Partly because of that, and partly because it

is a good airline anyway, Virgin Blue

now appears to be flourishing.

Flash

forward to 2003. Virgin Atlantic have

often stated their desire to be able to

operate flights to Australia, and their

interest has again surfaced to the point where

they're aggressively planning to start such

flights (if they can get permission from the

Australian government!).

Qantas

has again been understandably disparaging

about this - for sure, Qantas would very much

prefer not to see another major competitor on

its 'Kangaroo Route' (ie London-Sydney).

And

so, with this as background, please enjoy the

following open letter from Sir Richard to

Geoff Dixon, CEO of Qantas.

Sir

Richard Branson

24 July 2003

OPEN

LETTER TO GEOFF DIXON FROM RICHARD BRANSON

Dear

Geoff,

I

was amused to read Qantas’s completely

dismissive comments about Virgin Atlantic’s

chances of getting permission to fly to Australia. It would be prudent for you

to remind yourself of your and James

Strong’s equally dismissive comments about

Virgin Blue’s chances of entering the

Australian market only three years ago.

Here

goes! This is the gist of what you said:

-

“Virgin

Blue is a lot of media hype.”

-

“This

market is not big enough to sustain Virgin

Blue.”

-

“Virgin

Blue doesn’t have deep enough pockets to

cope.”

-

“Qantas

will employ any option to see off this

interloper.”

-

“They’ll

be unlikely to survive a year.”

-

“Claims

by Richard Branson that domestic fares are

high are a misnomer!” (my exclamation

mark)

Here

is what James Strong, your former C.E.O, said

about Virgin Blue and myself:

“If

you listen to most of the pretenders there

is a distinct air that they are making it up

as they go along. In terms of real plans and

real commitment you could fire a shot gun up

the main street and not hit anybody.”

Yet

three years later you are telling your staff

that this same airline, “that was making it

up as it went along” and that now has 30% of

the market could, “Drive Qantas out of

business!” We also find it flattering, if a

little silly, that three years on you now have

spies hiding behind pot plants in the Virgin

terminal trying to work out why we are so

successful.

Even

if some of your comments don’t suggest it,

your actions indicate you are taking us

seriously. But let’s not take ourselves too

seriously. I would like to propose a friendly

challenge!

If

Virgin Atlantic fails to fly to Australia

(within 18 months, say) I’d be prepared to

suffer the indignity of donning one of your

stewardesses brand new designer outfits and

will work your flight from London to Australia

serving your customers throughout.

However,

if Virgin Atlantic does fly to Australia you

would do so instead. On our inaugural flight

from London to Australia you would wear one of

our beautiful red Virgin Stewardesses uniforms

and serve our inaugural guests all the way to

Australia. Oh and in case you were

wondering, we’re not hung up on flying

through Hong

Kong. You might end up doing your

days work experience through Singapore,

Thailand or Malaysia instead.

This

is the challenge. If you believe in what

Qantas said to the press there can’t be any

risk for you. We expect your response within

one week. Our inaugural flights are great fun

and I look forward to welcoming you on board

personally. Oh and by the way my preferred

drink is ………..!

Kind

regards,

Richard.

p.s.

I enclose a picture to give you an idea of

what you might look like.

Dixon

wasn't impressed with Branson's offer.

"We

are running an airline not a circus,"

Dixon said through a Qantas spokeswoman.

|

Global

warming has unexpected consequences for competing groups

of scientists

each

wanting to take credit for themselves

for the

find of the century.

This

short story is being developed for release as a

full length novel (e-book)

for

2015 with storyboards

for a film in 2016

of ASAP thereafter.

|