|

MEGAPTERA

NOVAEANGLIAE

Length: 13–17 meters

Weight: 25–40 tons.

Worldwide population: 10.000–15.000 individuals

Life expectancy: Ca. 95 years

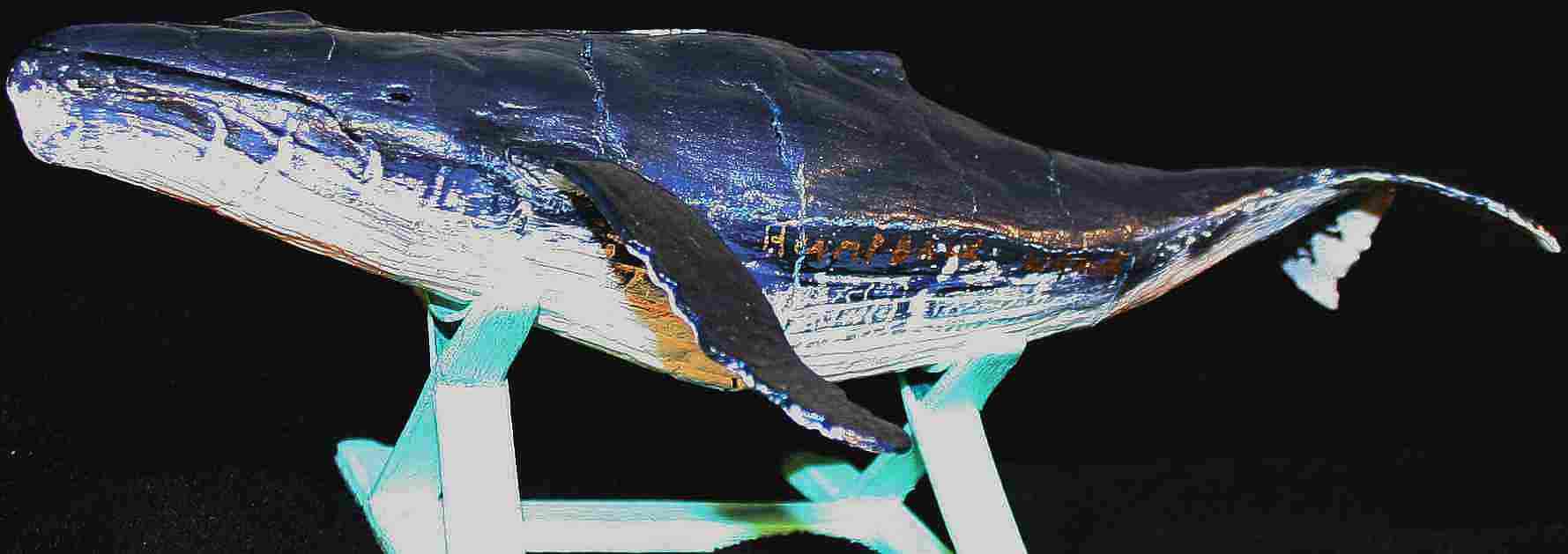

The

Humpback Whale famous for broaching

The

hump back whale in Icelandic waters is 12,5-13 m long.

The females weigh 30-48 tons and the males 25-35.

Its life expectancy is about 95 years.

The flippers are very long, usually black, or black and

white on top with a white underside, and their front edge is

knobby. The back is

black and the underside is light coloured.

The colour pattern on the neck and the breast are

variable. The

baleens are dark grey. The

white and black patterns on the underside of the flukes are used

as fingerprints to recognize the individuals.

The humpback whale occurs in all of the world’s oceans.

In the North Atlantic, the whales’ habitat reaches

between Northwest Africa and the West Indies to the ice edge in

the northern seas. Mating

takes place during the migration in March-May, the gestation

period is 11 months and pregnancy occurs every two years.

The calf is 4½-5 m long at birth and is suckled for 5

months.

The mainstay of the food is krill, but also small fishes, such

as capelin and herring. Humpbacks

are often found in shoals of 2-20 animals and are rather slow

swimmers. Their

curiosity often draws them to passing vessels and sometimes they

leap high out of the water.

Each dive takes 15-20 minutes and sometimes a few animals

round scattered schools of small fishes up by releasing air from

below them and then ascend gaping to fill their mouths.

They communicate or “sing” much during the mating

period and are observed closed to shore than other large

species.

Humpbacks were a rare species off the Icelandic coast after the

overexploitation of the Norwegians and have been totally

protected since 1955. Their

main summer habitats were off the east- and southeast coast, but

they were caught all around the country.

Parts of the stocks remain in the northern seas during

winter as well. Pregnant

cows swim south to give birth and then return in summer.

American harpoons have been found in humpbacks off the

North Norwegian coast.

Humpbacks are among the most spotted species during whale

watching tours all around the country.

A

Humpback Whale with fish attached

The humpback whale

(Megaptera novaeangliae) is a species of baleen whale. One of the larger rorqual species, adults range in length from 12–16 metres (39–52 ft) and weigh approximately 36,000 kilograms (79,000 lb). The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with unusually long pectoral fins and a knobbly head. It is an acrobatic animal, often breaching and slapping the water. Males produce a complex song, which lasts for 10 to 20 minutes and is repeated for hours at a time. The purpose of the song is not yet clear, although it appears to have a role in mating.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 25,000 kilometres (16,000 mi) each year. Humpbacks feed only in summer, in polar waters, and migrate to tropical or sub-tropical waters to breed and give birth in the winter. During the winter, humpbacks fast and live off their fat reserves. The species' diet consists mostly of krill and small fish. Humpbacks have a diverse repertoire of feeding methods, including the bubble net feeding technique.

Like other large whales, the humpback was and is a target for the whaling industry. Due to over-hunting, its population fell by an estimated 90% before a whaling moratorium was introduced in 1966. Stocks have since partially recovered; however, entanglement in

fishing gear, collisions with ships, and noise pollution also remain concerns. There are at least 80,000 humpback whales worldwide. Once hunted to the brink of extinction, humpbacks are now sought by whale-watchers, particularly off parts of

Australia, New

Zealand, South

America, Canada, and the United States.

|

|

|

|

|

|

B.

physalus (fin

whale)

|

|

|

|

B.

edeni (pygmy

Bryde's whale)

|

|

|

|

B.

borealis

(Sei

whale)

|

|

|

B.

brydei

(Bryde's

whale)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B.

musculus (blue

whale)

|

|

|

Megaptera

novaeangliae

(humpback whale)

|

|

|

Eschrichtius

robustus (gray

whale)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A phylogenetic tree of animals related to the humpback whale

Taxonomy

Humpback whales are rorquals (family

Balaenopteridae), a family that includes the blue whale, the fin whale, the Bryde's whale, the sei whale and the minke whale. The rorquals are believed to have diverged from the other families of the suborder Mysticeti as long ago as the middle

Miocene. However, it is not known when the members of these families diverged from each other.

Though clearly related to the giant whales of the genus

Balaenoptera, the humpback has been the sole member of its genus since Gray's work in 1846. More recently though, DNA sequencing analysis has indicated the Humpback is more closely related to certain

rorquals, particularly the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), and possibly to the gray whale

(Eschrichtius robustus), than it is to rorquals such as the minke

whales. If further research confirms these relationships, it will be necessary to reclassify the

rorquals.

The humpback whale was first identified as "baleine de la Nouvelle

Angleterre" by Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Regnum Animale of 1756. In 1781, Georg Heinrich Borowski described the species, converting Brisson's name to its Latin equivalent, Balaena

novaeangliae. In 1804, Lacépède shifted the humpback from the Balaenidae family, renaming it Balaenoptera

jubartes. In 1846, John Edward Gray created the genus Megaptera, classifying the humpback as Megaptera

longipinna, but in 1932, Remington Kellogg reverted the species names to use Borowski's

novaeangliae. The common name is derived from the curving of their back when diving. The generic name Megaptera from the Greek mega-/μεγα- "giant" and

ptera/πτερα

"wing", refers to their large front flippers. The specific name means "New Englander" and was probably given by Brisson due the regular sightings of humpbacks off the coast of New

England.

The

head of a young humpback whale

Description

A humpback whale can easily be identified by its stocky body with an obvious hump and black dorsal coloring. The head and lower jaw are covered with knobs called tubercles, which are actually hair follicles, and are characteristic of the species. The fluked tail, which it lifts above the surface in some dive sequences, has wavy trailing

edges. The four global populations, all under study, are: North Pacific, Atlantic, and Southern Ocean humpbacks, which have distinct populations which complete a migratory round-trip each year and the

Indian Ocean population, which does not migrate, prevented by that ocean's northern coastline.

The long black and white tail fin, which can be up to a third of body length, and the pectoral fins have unique patterns, which make individual whales

identifiable. Several hypotheses attempt to explain the humpback's pectoral fins, which are proportionally the longest fins of any cetacean. The two most enduring mention the higher maneuverability afforded by long fins, and the usefulness of the increased surface area for temperature control when migrating between warm and cold climates. Humpbacks also have

'rete mirabile', a heat exchanging system, which works similarly in humpbacks, sharks and other

fish.

A tail from a different individual - the tail of each humpback whale is visibly unique.Humpbacks have 270 to 400 darkly coloured baleen plates on each side of the mouth. The plates measure from a mere 18 inches (46 cm) in the front to approximately 3 feet (0.91 m) long in the back, behind the hinge. Ventral grooves run from the lower jaw to the umbilicus about halfway along the underside of the whale. These grooves are less numerous (usually 16–20) and consequently more prominent than in other

rorquals.

The stubby dorsal fin is visible soon after the blow when the whale surfaces, but disappears by the time the flukes emerge. Humpbacks have a 3 metres (9.8 ft) heart-shaped to bushy blow, or exhalation of water through the blowholes. Because Humpback Whales breathe voluntarily, it is possible that the whales shut off only half of the brain when

sleeping. Early whalers also noted blows from humpback adults to be 10–20 feet (3.0–6.1 m) high.

Newborn calves are roughly the length of their mother's head. At birth, calves measure 20 feet (6.1 m) at 2 short tons (1.8 t) The mother, by comparison, is about 50 feet (15 m). They nurse for approximately six months, then mix nursing and independent feeding for possibly six months more. Humpback milk is 50% fat and pink in color. Some calves have been observed alone after arrival in

Alaskan

waters.

Young

humpback whale with blowholes clearly visible

Females reach sexual maturity at the age of five, achieving full adult size a little later. Males reach sexual maturity at approximately 7 years of age. The humpback whale lifespan ranges from 45–100

years.

Fully grown, the males average 15–16 metres (49–52 ft). Females are slightly larger at 16–17 metres (52–56 ft), and 40,000 kilograms (44 short tons); the largest recorded specimen was 19 metres (62 ft) long and had pectoral fins measuring 6 metres (20 ft)

each.

Females have a hemispherical lobe about 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in diameter in their genital region. This visually distinguishes males and females. The male's penis usually remains hidden in the genital slit. Male whales have distinctive scars on heads and bodies, some resulting from battles over

females.

Identifying individuals

The varying patterns on the tail flukes are sufficient to identify individuals. Unique visual identification is not currently possible in most cetacean species (other exceptions include orcas and right whales), making the humpback a popular study

species. A study using data from 1973 to 1998 on whales in the North Atlantic gave researchers detailed information on gestation times, growth rates, and calving periods, as well as allowing more accurate population predictions by simulating the mark-release-recapture technique (Katona and Beard 1982). A photographic catalogue of all known North Atlantic whales was developed over this period and is currently maintained by College of the

Atlantic. Similar photographic identification projects have begun in the North Pacific by SPLASH (Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance and Status of Humpbacks), and around the world.

Reproduction

Females typically breed every two or three years. The gestation period is 11.5 months, yet some individuals have been known to breed in two consecutive years. The peak months for birth are January, February, July, and August. There is usually a 1-2 year period between humpback births. Humpback whales can live up to 48 years.

Recent research on humpback mitochondrial DNA reveals that groups that live in proximity to each other may represent distinct breeding

pools.

A humpback in the waters of the Abrolhos Archipelago

A humpback whale

broaching backwards

Social structure

Whale surfacing behaviour

Humpbacks frequently breach, throwing two thirds or more of their bodies out of the water and splashing down on their backs.

The humpback social structure is loose-knit. Typically, individuals live alone or in small, transient groups that disband after a few hours. These whales are not excessively social in most cases. Groups may stay together a little longer in summer to forage and feed cooperatively. Longer-term relationships between pairs or small groups, lasting months or even years, have rarely been observed. It is possible that some females retain bonds created via cooperative feeding for a lifetime. The humpback's range overlaps considerably with other whale and dolphin species — for instance, the minke whale. However, humpbacks rarely interact socially with them, though humpback calves in

Hawaiian waters sometimes play with bottlenose

dolphin

calves.

Courtship

Courtship rituals take place during the winter months, following migration toward the equator from summer feeding grounds closer to the poles. Competition is usually fierce, and unrelated males dubbed escorts by researcher Louis Herman frequently trail females as well as mother-calf dyads. Groups of two to twenty males gather around a single female and exhibit a variety of behaviors over several hours to establish dominance of what is known as a competitive group. Group size ebbs and flows as unsuccessful males retreat and others arrive to try their luck. Behaviors include breaching, spyhopping, lob-tailing, tail-slapping, fin-slapping, peduncle throws, charging and parrying. Less common "super pods" may number more than 40 males, all vying for the same female. (M. Ferrari et al.)

Whale song is assumed to have an important role in mate selection; however, scientists remain unsure whether song is used between males to establish identity and dominance, between a male and a female as a mating call, or

both.

A humpback whale tail displaying wavy rear edges

Whale song

Spectrogram of Humpback Whale vocalizations. Detail is shown for the first 24 seconds of the 37-second recording "Singing Humpbacks". The ethereal whale "songs" and echolocation "clicks" are visible as horizontal striations and vertical sweeps respectively. Spectrogram generated with Fatpigdog's PC based Real Time FFT Spectrum Analyzer. Singing Humpbacks

Both male and female humpback whales vocalize, however only males produce the long, loud, complex "songs" for which the species is famous. Each song consists of several sounds in a low register that vary in amplitude and frequency, and typically lasts from 10 to 20

minutes. Humpbacks may sing continuously for more than 24 hours. Cetaceans have no vocal cords, so whales generate their song by forcing air through their massive nasal cavities.

Whales within a large area sing the same song. All North Atlantic humpbacks sing the same song, and those of the North Pacific sing a different song. Each population's song changes slowly over a period of years without

repeating.

Scientists are unsure of the purpose of whale song. Only males sing, suggesting that one purpose is to attract females. However, many of the whales observed to approach a singer are other males, and results in conflict. Singing may therefore be a challenge to other

males. Some scientists have hypothesized that the song may serve an echolocative

function. During the feeding season, humpbacks make altogether different vocalizations for herding fish into their bubble

nets.

All these behaviors also occur absent potential mates. This indicates that they are probably a more general communication tool. Scientists hypothesize that singing may keep migrating populations connected. (Ferrari, Nicklin, Darling, et al.) Some observers report that singing begins when competition for a female

ends.

Humpback whales have also been found to make a range of other social sounds to communicate such as "grunts", "groans", "thwops", "snorts" and

"barks".

A group of 15 whales bubble net fishing near Juneau, Alaska

Ecology

Feeding

Humpbacks feed primarily in summer and live off fat reserves during

winter. They feed only rarely and opportunistically in their wintering waters. The humpback is an energetic hunter, taking krill and small schooling fish such as Atlantic herring, Atlantic

salmon, capelin, and American sand lance as well as Atlantic mackerel, pollock, and haddock in the North

Atlantic. Krill and copepods have been recorded as prey species in Australian and Antarctic

waters. Humpbacks hunt by direct attack or by stunning prey by hitting the water with pectoral fins or flukes.

The humpback has the most diverse feeding repertoire of all baleen

whales. Its most inventive technique is known as bubble net feeding: a group of whales swims in a shrinking circle blowing bubbles below a school of prey. The shrinking ring of bubbles encircles the school and confines it in an ever-smaller cylinder. This ring can begin at up to 30 metres (98 ft) in diameter and involve the cooperation of a dozen animals. Using a crittercam attached to a whale's back it was discovered that some whales blow the bubbles, some dive deeper to drive fish toward the surface, and others herd prey into the net by

vocalizing. The whales then suddenly swim upward through the 'net', mouths agape, swallowing thousands of fish in one gulp. Plated grooves in the whale's mouth allow the creature to easily drain all the water that was initially taken in.

Predation

Given scarring records, killer whales are thought to prey upon juvenile humpbacks, though this has never been witnessed. The result of these attacks is generally nothing more serious than some scarring of the skin, but it is likely that young calves are sometimes

killed.

Range and habitat

Humpbacks inhabit all major oceans, in a wide band running from the Antarctic ice edge to 77° N latitude, though not in the eastern Mediterranean or the Baltic Sea.

Humpbacks are migratory, spending summers in cooler, high-latitude waters and mating and calving in tropical and subtropical

waters. An exception to this rule is a population in the Arabian Sea, which remains in these tropical waters

year-round. Annual migrations of up to 25,000 kilometres (16,000 mi) are typical, making it one of the mammal's best-traveled species.

A large population spreads across the Hawaiian islands every winter, ranging from the island of Hawaii in the south to Kure Atoll in the

north. A 2007 study identified seven individuals wintering off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica as having traveled from the

Antarctic — around 8,300 kilometres (5,200 mi). Identified by their unique tail patterns, these animals made the longest documented mammalian

migration.

In Australia, two main migratory populations have been identified, off the west and east coast respectively. These two populations are distinct, with only a few females in each generation crossing between the two

groups.

Entangled

in rope, a humpback struggles

Whaling in Japan

Humpback whales were hunted as early as the 18th century, but distinguished by whalers as early as the first decades of the 17th century.

By the 19th century, many nations (the United States in particular), were hunting the animal heavily in the Atlantic Ocean, and to a lesser extent in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It was, however, the late 19th century introduction of the explosive harpoon that allowed whalers to accelerate their take. This, along with hunting in the Antarctic Ocean beginning in 1904, sharply reduced whale populations.

It is estimated that during the 20th century, at least 200,000 humpbacks were taken, reducing the global population by over 90%, with North Atlantic populations estimated to have dropped to as low as 700

individuals. In 1946, the International Whaling Commission was founded to oversee the whaling industry. They imposed rules and regulations for hunting whales and set open and closed hunting seasons. To prevent extinction, the International Whaling Commission banned commercial humpback whaling in 1966. By that time the population had been reduced to around

5,000. That ban is still in force.

Prior to commercial whaling, populations could have reached 125,000. North Pacific kills alone are estimated at

28,000. The full toll is much higher. It is now known that the Soviet Union was deliberately under-recording its catches; the

Soviet catch was reported at 2,820 whereas the true number is now believed to be over

48,000.

As of 2004, hunting of humpback whales was restricted to a few animals each year off the Caribbean island Bequia in the nation of St. Vincent and the

Grenadines. The take is not believed to threaten the local population.

Japan had planned to kill 50 humpbacks in the 2007/08 season under its JARPA II research program, starting in November 2007. The announcement sparked global

protests. After a visit to Tokyo by the chairman of the IWC, asking the Japanese for their co-operation in sorting out the differences between pro- and anti-whaling nations on the Commission, the Japanese whaling fleet agreed that no humpback whales would be caught for the two years it would take for the IWC to reach a formal

agreement.

In 2010 the International Whaling Commission authorized Greenland’s native population to hunt a few humpback whales for the next three

years.

A humpback whale

broaching sideways

Conservation

There are at least 80,000 humpback whales worldwide, with 18,000-20,000 in the North

Pacific, about 12,000 in the North Atlantic, and over 50,000 in the Southern

Hemisphere, down from a pre-whaling population of 125,000.

This species is considered "least concern" from a conservation standpoint, as of 2008. This is an improvement from vulnerable in the prior assessment. Most monitored stocks of humpback whales have rebounded well since the end of commercial

whaling, such as the North Atlantic where stocks are now believed to be approaching pre-hunting levels. However, the species is considered endangered in some countries, including the United

States. The United States initiated a status review of the species on August 12, 2009, and is seeking public comment on potential changes to the species listing under the U.S. Endangered Species

Act. Areas where population data is limited and the species may be at higher risk include the Arabian Sea, the western North Pacific Ocean, the west coast of Africa and parts of

Oceania.

Today, individuals are vulnerable to collisions with ships, entanglement in fishing gear, and noise

pollution. Like other cetaceans, humpbacks can be injured by excessive noise. In the 19th century, two humpback whales were found dead near sites of repeated oceanic sub-bottom blasting, with traumatic injuries and fractures in the

ears.

Once hunted to the brink of extinction, the humpback has made a dramatic comeback in the North Pacific. A 2008 study estimates that the humpback population that hit a low of 1,500 whales before hunting was banned worldwide, has made a comeback to a population of between 18,000 and

20,000.

Humpback Whale Skeleton on Display at The Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Saxitoxin, a paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) from contaminated mackerel has been implicated in humpback whale

deaths.

The United

Kingdom, among other countries, designated the humpback as a priority species under the national Biodiversity Action Plan.

The sanctuary provided by U.S. National Parks such as Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve and Cape Hatteras National Seashore, among others, have also become major factors in sustaining

populations.

Although much was learned about humpbacks from whaling, migratory patterns and social interactions were not well understood until two studies by R. Chittleborough and W. H. Dawbin in the

1960s. Roger Payne and Scott McVay made further studies of the species in

1971. Their analysis of whale song led to worldwide media interest and convinced the public mind that whales were highly intelligent, aiding the anti-whaling advocates.

In August 2008, the IUCN changed humpback's status from Vulnerable to Least Concern, although two subpopulations remain

endangered.

The United States is considering listing separate humpback populations, so that smaller groups, such as North Pacific humpbacks, which are estimated to number 18,000-20,000 animals, might be

de-listed. This is made difficult by humpback's extraordinary migrations, which can extend the 5,157 miles (8,299 km) from Antarctica to Costa

Rica.

Whale watching

Humpback whales are generally curious about objects in their environment. Some individuals, referred to as "friendlies", approach whale-watching boats closely, often staying under or near the boat for many minutes. Because humpbacks are often easily approachable, curious, easily identifiable as individuals, and display many behaviors, they have become the mainstay of whale-watching tourism in many locations around the world. Hawaii has used the concept of "eco tourism" to use the species without killing them. This whale watching business attracts 1 million visitors a year, which results in a profit of

$80

million.

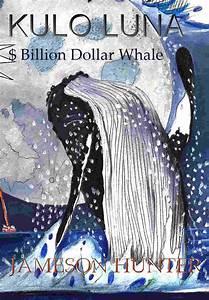

Kulo

Luna is a modern Moby Dick with an environmental twist

The

film production company Blueplanet Netdirect are developing

a

script from this book by Jameson Hunter

There are many commercial whale-watching operations on both the humpback's summer and winter

ranges:

North Atlantic North Pacific Southern Hemisphere

Summer

New England, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, the northern St. Lawrence River, the Snaefellsnes peninsula in the west of Iceland California,

Alaska, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia Antarctica, Bahía Solano and Nuquí in

Colombia

Winter

Samaná Province of the Dominican Republic, the Bay of Biscay France, Hawaii, Baja, the Bahía de Banderas off Puerto Vallarta Sydney, Byron Bay north of Sydney, Hervey Bay north of Brisbane, North and East of Cape Town,

New Zealand, the Tongan islands,

As with other cetacean species, however, a mother whale is generally extremely protective of her infant, and places herself between any boat and her calf before moving quickly away from the vessel. Skilled tour operators avoid stressing the

mother.

The

Aleutian Islands - Humpback feeding ground

Famous

humpbacks

Migaloo

A presumably albino humpback whale that travels up and down the east coast of Australia has become famous in the local media, on account of its extremely rare all-white appearance. Migaloo is the only known all-white humpback whale in the

world. First sighted in 1991 and believed to be 3–5 years old at that time, Migaloo is a word for "white

fella" from one of the languages of the Aboriginals, the Indigenous Australians. Speculation about Migaloo's sex was resolved in October 2004 when researchers from Southern Cross University collected sloughed skin samples from Migaloo as he migrated past Lennox Head, and subsequent genetic analysis of the samples proved he is a male. Because of the intense interest, environmentalists feared that he was becoming distressed by the number of boats following him each day. In response, the Queensland and New South Wales governments introduce legislation each year to create a 500 m (1600 ft) exclusion zone around the whale. Recent close up pictures have shown Migaloo to have skin cancer and/or skin cysts as a result of his lack of protection from the

sun.

In 2006, a white calf was spotted with a normal humpback mother in Byron Bay, New South

Wales.

A

dead beached humpback whale, California

Humphrey the Whale

One of the most notable humpback whales is Humphrey the Whale, twice-rescued by The Marine Mammal Center and other concerned groups in

California. In 1985, Humphrey swam into San Francisco Bay and then up the Sacramento River towards Rio

Vista. Five years later, Humphrey returned and became stuck on a mudflat in San Francisco Bay immediately north of Sierra Point below the view of onlookers from the upper floors of the Dakin Building. He was pulled off the mudflat with a large cargo net and the help of the Coast Guard. Both times he was successfully guided back to the Pacific Ocean using a "sound net" in which people in a flotilla of boats made unpleasant noises behind the whale by banging on steel pipes, a Japanese fishing technique known as "oikami." At the same time, the attractive sounds of humpback whales preparing to feed were broadcast from a boat headed towards the open

ocean. Since leaving the San Francisco Bay in 1990 Humphrey has been seen only once, at the Farallon Islands in 1991.

HUMPBACK

FICTION - KULO LUNA

Like

Moby

Dick, Kulo Luna is a fictional animal in the book of the

same name. In Herman

Melvilles's book, the antagonist is a giant sperm whale of

the same name. In Jameson

Hunter's book, the antagonist is a Japanese whaling cartel.

In the days of Moby Dick, whaling was neither immoral nor

illegal. Times have changed. Having nearly wiped them out, the

vast majority of humans are

actively protecting whales.

Whereas

Moby Dick is set in the 1850s, Kulo Luna is set slightly in the

future. The human protagonist captains a robot

solar powered boat named SolarNavigator, seen at the foot of

this page. The boat is the subject of a real autonomous

research project for 2013. The story is not that far moved from

reality in that the Japanese still hunt whales and there are

many organisations trying to prevent them from killing these

fabulous animals.

LINKS:

Which

way now?

Environmentalists

hope to save the whales - again

-

Humpback

whale songs

-

Conservation

Japan

backs Iceland's whaling decision Seattle Post

Intelligencer - 18 Oct 2006

TOKYO -- Major pro-whaling nation Japan on

Wednesday welcomed Iceland's decision to resume

commercial whaling, saying Iceland's catch

won't "endanger the whale ...

Iceland

whaling decision condemned Stuff.co.nz

Greenpeace

'disappointed' by Iceland's whaling plans ABC

Online

Moves

begin on Iceland's whaling BBC News

Monsters

and Critics.com - Radio

New Zealand

Greens

dismayed at Iceland whaling decision

Scoop.co.nz (press release), New Zealand - 17

Oct 2006

News that Iceland is to begin commercial whaling

after a 20-year hiatus is being greeted with dismay by

Green Party Conservation Spokesperson Metiria Turei. ...

Iceland

to Resume Commercial Whaling

Los Angeles Times, CA - 17 Oct 2006

REYKJAVIK, Iceland -- Iceland said Tuesday

it would resume commercial whaling after a nearly

two-decade moratorium, defying a worldwide ban on

hunting the ...

Green

warrior to come to Iceland IcelandReview, Iceland -

20-10-06

... According to RÚV, the US government is also

opposed to Iceland resuming commercial whaling

and has the power to block all imports from Iceland

to USA. ...

Today's

Scoop Just Politics News Summary 17

Oct 2006

Scoop.co.nz (press release), New Zealand - commercial whaling administered by the

International Whaling Commission. See... Greens

dismayed at Iceland whaling decision

Update:

Finnair strike expected to continue next week

International Herald Tribune, France -

hours ago

... "We have received several e-mails from

people saying they have decided not to visit Iceland

as long as Iceland is conducting whaling,"

said Thorunn ...

Tharp She Gets Shot! The Return of Whaling in Iceland

19 Oct 2006

Plenty Magazine, NY -

which Iceland’s whales have been protected from hunters came to an end on Tuesday, when the country’s

lawmakers voted to resume commercial whaling in the ...

Whaling

is affecting tourism IcelandReview, Iceland -

19 Oct 2006

... of Swiss travel agency Baldinger Reisen AG sent a written statement to icelandreview.com yesterday,

expressing his concerns about Iceland resuming whaling.

...

Iceland,

Whales, Politics

FiNS Magazine, Singapore - 18 Oct 2006

... For a good overview on the Iceland

decision and the issues associated with commercial whaling

in general, see this recent article in the Guardian. ...

Iceland

to resume commercial whaling after almost 2

decades

USA Today 17-10-06

Critics say the "scientific" whaling

practiced by Japan and Iceland is a sham. Norway

ignores the moratorium altogether and openly conducts

commercial whaling.

Iceland's

Whaling Comeback

- Preparations for the Resumption of ...

The

Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) is the leading

international charity dedicated solely to the worldwide conservation and

welfare of all ... www.wdcs.org/dan/publishing.nsf/

allweb/B2460680BC28D8F480256D4A0040D97B

BBC

NEWS | Science/Nature | Moves begin on Iceland's whaling

Iceland's

ambassador to Britain is summoned to explain his country's return to

commercial whaling. news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/6064028.stm

A

1/100th scale sculpture of a humpback whale made of white bread,

which,

unfortunately cracks a lot when drying out.

BBC

NEWS | Science/Nature | Iceland bids to resume whaling

Iceland

reveals its plans to catch whales again for the first time since 1989,

despite the international whaling moratorium. news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/2910655.stm

Iceland

Whaling v/s Whale watching. Whaling v/s Whale

watching.

The

most commonly used argument in Iceland is that whaling must

be resumed before the whales start ... Yearly report on Iceland

whale watching industry: ... www.global500.org/news_83.html

Iceland

My

opinion: Iceland's reasons for scientific whaling are FUBAR

and if we can ... I wonder how many of you criticising Iceland's

whaling have actually read ... weblog.greenpeace.org/iceland/archives/001530.html

Stop

Icelandic whaling

Stop

Icelandic Whaling: Arctic Sunrise Expedition 2005, Stop Icelandic

Whaling: Arctic ... tourism in Iceland IF Iceland

discontinues whaling. One Icelandic ...

weblog.greenpeace.org/iceland/archives/2003_09.html

Greenpeace

'disappointed' by Iceland's whaling plans. 19/10/2006

Greenpeace

says it is very disappointed Iceland has decided to resume

commercial whaling Iceland has authorised an annual hunt of 30

minke and nine of the ...

www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200610/s1768443.htm

Earth

Island Institute

Iceland's

whaling proposal threatens its growing whale-watching industry.

In 2002, more than 62000 people went whale-watching in Iceland.

...

www.earthisland.org/takeaction/new_action.cfm?aaID=167

Japan

backs Iceland's whaling decision - Yahoo! News

Major

pro-whaling nation Japan on Wednesday welcomed Iceland's

decision to resume commercial whaling, saying Iceland's

catch won't "endanger the whale ...

news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20061019/

ap_on_re_eu/japan_iceland_whaling

Whales

on the Net - Iceland Whaling Protest Letter

I

am appalled to learn that Iceland has decided to resume commercial whaling

under the guise of scientific research, and plans to kill 38 minke whales

this ... www.whales.org.au/alert/iceletter.html

-

"Order

Cetacea (pp. 723-743)". In Wilson, Don E., and

Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds.

-

Mammal

Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference

(3rd ed.).

-

http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14300027.

-

Donovan,

G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. (2008). Megaptera

novaeangliae.

-

"Whale

Evolution" (PDF). McGraw-Hill Yearbook of

Science & Technology. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~gingeric/PDFfiles/PDG413_Whaleevol.pdf.

-

"Cetacean

mitochondrial DNA control region". Molecular

Biology and lution http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/10/5/960.

-

"Mitochondrial

Phylogenetics and Evolution of Mysticete Whales". Systematic

Biology 54 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1080/10635150590905939. 15805012.

-

Recovery

Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megapten Novaeangliae).

NOAA 1991.

http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/recovery/whale_humpback.pdf.

-

"Resting

behavior in a rehabilitating gray whale calf" (pdf).

Aquatic Mammals 27.3: 256–266.

-

"Whalenet

Data Search". Wheelock College.

http://www.coa.e/alliedwhaleresearch.htm.

-

"Whale

Watch: Endangered Designation In Danger". The

Wall Street Journal.

-

"American

Cetacean Society Fact Sheet".

-

Public

Broadcasting Station. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/humpback/song.html.

-

"Humpback

Whale Song or Sonar? A Reply to Au et al" (PDF).

-

IEEE

Journal of Oceanic Engineering 26 (3): 406–415.

doi:10.1109/48.946514.

-

http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~emiii/00946514.pdf.

-

"Stereotypical

sound patterns in humpback whale songs" (PDF). Aquatic

Mammals 29

-

www.whaletrust.com

-

Cecilia

Burke, ''A

whale's varied vocabulary', Australian Geographic, AG

Online.

-

Humpback

whale. eds. C.Michael Hogan and C.J.Cleveland,

Encyclopedia of Earth

-

Acklin,

Deb (2005-08-05). "Crittercam

Reveals Secrets of the Marine World". National

Geographic News.

-

"The

social and reproductive biology of humpback whales: an

ecological perspective"

-

"Southern

Hemisphere humpback water temperature longest mammalian

migration"

-

"Megaptera

novaeangliae Species Profile &Threats".

Australian Government: DOEWR

2007.

-

"Abundant

mitochondrial DNA variation in humpback whales" (PDF)

-

Prof.

Alexey V. Yablokov (1997). "On

the Soviet Whaling Falsification, 1947–1972".

-

scoop.co.nz:

Leave

Humpback Whales Alone Message To Japan 16 May 2007

-

Hogg,

Chris (2007-12-21). "Japan

changes track on whaling". BBC News.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/7156288.stm.

-

"WORLD

BRIEFING". The New York Times: p. 7. 26

June 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/26/science/earth/26briefs-WHALES.html.

-

"Humpbacks

Make a Splash in the N. Pacific". Wildwhales.org.

2008-05-23. http://wildwhales.org/2008/05/humpbacks-make-a-splash-in-the-north-pacific/.

-

"NOAA

SARS Humpback whales, North Atlantic".

Nmfs.noaa.gov. 2008-04-01. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/sars/ao2006_whhb-gme.pdf.

-

"Humpback

whale abundance south of 60°S from three circumpolar

surveys"

-

"Study:

Humpback whale population is rising".

-

"US

National Marine Fisheries Service humpback whale web

page". Nmfs.noaa.gov. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/cetaceans/humpbackwhale.htm.

-

"Humpback

Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)".Alaska

Department of Fish and Game. 2006. http://www.adfg.state.ak.us/special/esa/whale_humpback/humpback_whale.php.

-

"Initiation

of a Status Review for the Humpback Whale".

Edocket.access.gpo.gov. http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2009/E9-19336.htm.

-

"Humpback

Whales Make Dramatic Comeback". Fox News.

Associated Press.

-

Dierauf

L & Gulland F (2001). Marine Mammal Medicine. CRC

Press.

-

"Humpback

Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". National Parks

Conservation Association. http://www.npca.org/protecting-our-parks/wildlife_facts/humpbackwhale.html.

-

"Humpback

whale on road to recovery, reveals IUCN Red List".

IUCN. 2008-08-12. http://cms.iucn.org/index.cfm?uNewsID=1413.

-

"Exclusion

zone for special whale". BBC News. 2009-06-30.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/8126237.stm.

-

"Migaloo,

the White Humpback Whale". Pacific Whale

Foundation. 2004.

-

New

white whale spotted

.

Solarnavigator

is a whale friendly trimaran with an extremely efficient

active

hull that runs on clean renewable solar power - a boat in harmony

with nature.

RODENTS:

|

Beaver

Capybara

Chinchilla

Chipmunk

Dormice

Gerbil

Guinea

Pig

Hamster

Mice

Porcupine

Prairie

Dog

Rat

Squirrel

Vole

|

OTHER

ANIMALS:

POPULAR

MAMMALS:

BIRD

INDEX:

|

Albatros

Bishop,

Orange

Blue

Bird

Canary

Chaffinch

Chicken

Cockatoo

Corella, Long-Billed

Cormorant

Crane, African Crowned

Crane

Crow

Cuckoo

Dodo

Dove

Duck

Eagle

Egret, Cattle

Emu

Falcon

Finch

Fishers Lovebird

Flamingo

Grebe

Goose, Egyptian

Grouse

Guinea Fowl, Helmeted

Hammerkop

Hawk

Hornbill, Wreathed

Hornbill, Red-Billed

Hottentot, Teal

House

Martin

Ibis, Hadada

Ibis,

Sacred

Kite, Black

Kingfisher

|

Kiwi

Kookaburra

Lapwing Plover

Lilac-Breasted

Roller

Loon

Macaw

Mynah

Nightjar

Ostrich

Owl

Parrot,

Amazon

Parrot

Partridge

Peacock

Pelican

Penguin

Petrel

Pheasant

Pigeon

Quail

Robin

Roller, Blue-Bellied

Seagull

Sparrow

Spoonbill African

Starling

Stork

Swan

Swift

Toucan

Turkey

Vulture, Griffon

Wader

Weaver, Taveta Golden

Woodcock

Woodpecker

|

POPULAR

INSECTS:

|

Ants

Apid

Army

Ant

Bee

Beetles

Bulldog

Ant

Butterfly

Centipede

Cockroach

Crickets

Damsel

Fly

Death

Watch Beetle

Dragonfly

Dung

Beetle

Earwig

Fly

Grasshopper

Hornet

|

Ladybird

Leafcutter

Ant

Locust

Mantis,

Preying

Maybug

Millipede

Mosquito

Moth

Praying

Mantis

Scarab

Beetle

Stag

Beetle

Stick

Insect

Termite

Wasp

Water

Boatman

Wood

Ant

Woodlice

Woodworm |

|

Blueplanet

Productions 2014 - 2016

|

The

Adventures of John Storm: KULO

LUNA™ - The $Billion Dollar Whale © BUH

Ltd MMXIII |

|

|

Title: |

The

Billion Dollar Whale |

. |

|

Format: |

35mm

Anamorphic 3D* |

to

HD DVD Blu-Ray |

|

Ratio: |

20

to 1* |

. |

|

Runtime: |

110

minutes |

. |

|

Pre-production: |

39

weeks |

. |

|

Shooting: |

11

weeks |

. |

|

Post-production |

15

weeks |

. |

|

A.

Pre-production

unit costs

|

55,370.00 |

L.

Travel

/ hotel accommodation

|

335,000.00 |

|

B.

Above

the line costs -prod execs |

25,907,500.00 |

M.

Publicity

/ screenings |

176,400.00 |

|

C.

Crew

- Main unit |

693,803.00 |

N.

Legal,

accounting. ins (Int, film guarantors) |

477,010.00 |

|

D.

Crew

- 2nd & 3rd units |

278,680.00 |

O.

Contingency

@ 10% |

7,254,830.00 |

|

E.

Cast

+ options |

20,290,000.00 |

P.

Producer's

/ Director's dividends (%) |

TBA |

|

F.

Computer

graphics (CGI) |

17,500,000.00 |

Q.

Distribution

- Direct (costs) |

27,959,000.00 |

|

G.

Art

department |

986,300.00 |

R.

Profit

projected on sales (before corp. tax) |

536,370,000.00 |

|

H.

Equipment |

242,850.00 |

S.

Finance

/ Interest

(5 yrs) |

53,876,570.00 |

|

I.

Location

/ transport / catering |

809,502.00 |

T.

Total

target film cost (production & distribution) |

107,753,138.00 |

|

J.

Stock,

lab, video transfers |

312,195.00 |

U.

Studio

property / equipment (invest) |

TBA |

|

K.

Post

production |

190,510.00 |

. |

. |

|

|

|

. |

. |

|

|

|

Sales |

*698,000,000.00 |

|

|

|

Cost

of Sales |

161,629,710.00 |

|

|

|

Net

Profit* |

*Subj.

corp. taxes |

|

. |

|

. |

|

|