|

DRESSAGE

|

||

|

Dressage (a French term meaning "training") is a path and destination of competitive horse training, with competitions held at all levels from amateur to Olympic. Its fundamental purpose is to develop, through standardized progressive training methods, a horse's natural athletic ability and willingness to perform, thereby maximizing its potential as a riding horse. At the peak of a dressage horse's gymnastic development, it can smoothly respond to a skilled rider's minimal aids by performing the requested movement while remaining relaxed and appearing effortless. For this reason, dressage is occasionally referred to as "Horse Ballet." Although the discipline has its roots in classical Greek horsemanship, dressage was first recognized as an important equestrian pursuit during the Renaissance in Western Europe. The great European riding masters of that period developed a sequential training system that has changed little since then and is still considered the basis of modern dressage.

Dressage

Early European aristocrats displayed their horses' training in equestrian pageants, but in modern dressage competition, successful training at the various levels is demonstrated through the performance of "tests," or prescribed series of movements within a standard arena. Judges evaluate each movement on the basis of an objective standard appropriate to the level of the test and assign each movement a score from zero to ten - zero being "not executed" and 10 being "excellent." A score of 9 (or "very good") is considered a particularly high mark.

The arena

There are two sizes of arenas: small and standard. The small arena is 20 m by 40 m, and is used for the lower levels of dressage and three-day eventing dressage. The standard arena is 20 m by 60 m, and is used for upper-level tests in both dressage and eventing. Since the combination of CEF and USDF tests in 2003, the small size arena is no longer utilized in rated shows in North America.

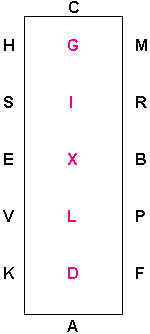

Dressage arenas have a lettering system around their outside in the order (clockwise) A-K-E-H-C-M-B-F (small arena) and A-K-V-E-S-H-C-M-R-B-P-F (standard arena). It is currently unknown who began the lettering system or why the arrangement was chosen. At the start of the test, the horse enters at A. There is always a judge sitting at C (although for upper-level competition, there are up to five judges at different places around the arena). There are also invisible letters along the centerline, D-X-G (small arena) and D-L-X-I-G (standard arena), X always being in the center of the dressage arena.

The dressage arena also has a centerline (from A to C, going through X in the middle), as well as two quarter-lines (halfway between the centerline and long sides of each arena). Olympic level

The dressage tests performed at the Olympic Games, which were accepted as sport in 1912, are those of the highest level-Grand Prix. This level of test demands the most skill and concentration from both horse and rider.

Gaits and movements performed at this level include collected and extended walk, trot, and canter; trot and canter half-pass (a movement where the horse travels on a diagonal line keeping its body almost parallel with the arena wall while making both forward and sideways steps in each stride); passage (a slow-motion trot); piaffe (an approach to "trot in place"); one and two tempi changes (where the horse changes from one lead to the other in the canter, when all four legs are in the air); canter "zigzags"; and pirouettes (a 360-degree circle that is almost in place).

Tests ridden at the Olympic Games are scored by a panel of five international judges. Each movement in each test receives a numeric score and the resulting final score is then converted into a percentage, which is carried out to three decimal points. The higher the percentage, the higher the score.

Olympic team medals are won by the teams with the highest, second highest, and third highest total percentage from their best three rides in the Grand Prix test.

Once the team medals are determined, horses and riders compete for individual medals. The team competition serves as the first individual qualifier, in that the top 25 horse/rider combinations from the Grand Prix test move on to the next round. The second individual qualifier is the Grand Prix Special test, which consists of Grand Prix movements arranged in a different pattern. For those 25 riders, the scores from the Grand Prix and the Grand Prix Special are then combined and the resulting top 15 horse/rider combinations move on to the individual medal competition-the crowd-pleasing Grand Prix Freestyle.

For their freestyles, riders and horses perform specially choreographed patterns to music. At this level, the freestyle tests may contain all the Grand Prix movements, as well as double canter pirouettes, pirouettes in piaffe, and half-pass in passage. For the freestyle, judges award technical marks for the various movements, as well as artistic marks. In the case of a tie, the ride with the higher artistic marks wins. [1]

Apart from competition, there is a tradition of Classical Dressage, in which purists pursue the tradition of dressage as an art form, for its own joy and beauty. Dressage is also a part of the Portuguese and Spanish bullfighting exhibitions. The traditions of the Old Masters who originated Dressage are kept alive by the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Austria and the Cadre Noir in Saumur, France.

Breeds commonly used for competitive dressage are normally in the warmblood category, as these breeds have the vigorous, extended movement and strength necessary for the sport. However, Dressage is an egalitarian sport in which all breeds are given an opportunity to compete successfully. Iberian horses such as the Andalusian, Lusitano and Lipizzaner are particularly popular among practitioners of classical dressage. These breeds excel in the collected movements of classical dressage.

Arena 60x20 letter arrangement

The Training Scale

The dressage training scale is arranged in a pyramid fashion, with “rhythm and regularity” at the bottom of the pyramid and “collection” at the top. The training scale is used as a guide for the training of the dressage horse (or any horse, for that matter). Despite its appearance, the training scale is not meant to be a rigid format. Instead, each level is built on as the horse progresses in his training: so a Grand Prix horse would work on the refinement of the bottom levels of the pyramid, instead of focusing on only the highest level: “collection.” The levels are also interconnected. For example, a crooked horse is unable to develop impulsion, and a horse that is not relaxed will be less likely to travel with a rhythmic gait.

Rhythm and Regularity (Takt)

Both rhythm and regularity should be the same on straight and bending lines, through lateral work, and through transitions. Rhythm refers to the sequence of the footfalls, which should only include the pure walk, pure trot, and pure canter. The regularity, or purity, of the gait includes the evenness and levelness of the stride.

Relaxation (Losgelassenheit)

The second level of the pyramid is relaxation (looseness). Signs of looseness in the horse may be seen by an even stride that is swinging through the back and causing the tail to swing like a pendulum, looseness at the poll, a soft chewing of the bit, and a relaxed blowing through the nose. The horse will make smooth transitions, be easy to position from side to side, and will willingly reach down into the contact as the reins are lengthened.

Contact (Anlehnung)

Contact—the third level of the pyramid—is the result of the horse’s pushing power, and should never be achieved by the pulling of the rider’s hands. The rider drives the horse into soft hands that allow the horse to come up into the bridle, and should always follow the natural motion of the animal’s head. The horse should have equal contact in both reins.

Impulsion (Schwung)

The pushing power (thrust) of the horse is called “impulsion,” and is the fourth level of the training pyramid. Impulsion is created by storing the energy of engagement (the forward reaching of the hind legs under the body). It is a result of:

• Correct driving aids of the rider • Relaxation of the horse • Throughness (durchlässigkeit): the flow of energy through the horse from front to back and back to front. The musculature of the horse is connected, supple, elastic, and unblocked, and the rider’s aids go freely through the horse.

Impulsion only occurs in the trot and canter—not the walk—because it is associated with the moment of suspension found in these two gaits.

Straightness (Geraderichtung)

A horse is straight when his hind legs follow the path of his front legs, on both straight lines and on bending lines, and his body is parallel to the line of travel. Straightness causes the horse to channel his impulsion directly toward his center of balance, and allows the rider’s hand aids to have a connection to the hind end.

Collection (Versammlung)

At the apex of the training scale, collection may be used occasionally to supplement less vigorous work, but is only focused on (through the collected gaits and more difficult movements, such as flying changes) in more advanced horses. Collection requires greater muscular strength, so must be developed slowly.

When a horse collects, he naturally takes more of his weight onto his hindquarters. The joints of the hind limbs have greater flexion, allowing the horse to lower his hindquarters, bring his hind legs further under his body, and lighten the forehand. A collected horse is able to move more freely. When collected, the stride length should shorten, and increase in energy and activity. Airs above the ground

These are a series of higher-level dressage maneuvers where the horse leaps above the ground. These include the capriole, courbette, croupade, and levade. None are typically seen in modern competitive dressage, but are performed by horses of various riding academies, including the Spanish Riding School in Vienna and the Cadre Noir in Saumur.

In the capriole, the horse jumps from a raised position of the forehand straight up into the air, kicks out with the hind legs, and lands more or less on all four legs at the same time. It requires an enormously powerful horse to perform correctly.

In the courbette, the horse raises his forehand off the ground, tucks up his forelegs evenly, and then jumps forward, never allowing the forelegs to touch down, in a series of "hops". Extremely strong and talented horses can perform five or more leaps forward before having to touch down with the forelegs. It is more usual to see a series of three or four leaps.

In the levade, the horse rises on his haunches to an angle of approximately 35 degrees from the ground, with both forelegs tucked up evenly, and balances in that position. At the beginning of the movement, the hind feet come under the horse's center of gravity with the hocks coming lower to the ground, so that the horse appears to sink down in back and rise in front. The position is held for a number of seconds, and then the horse quietly puts the forelegs back on the ground and proceeds at the walk, or stands at the halt. The purpose of the levade was to raise the rider out of reach of an enemy's sword. It is also a transition movement between work on the ground and the airs above the ground, and it requires enormous strength of the horse — not many horses are capable of a good quality levade.

The croupade is similar to the capriole, but the horse does not kick out at the height of elevation, but keeps his hind legs tucked tightly under.

The ballotade is similar to the croupade, but the horse's hind hooves are positioned so one can see its shoes if watching from behind. It appears as if the horse is ready to kick. The back of the horse is almost parallel to the ground. This is a transition movement to the more difficult capriole.

In the mezair, the horse rears up and strikes out with its forelegs. It is similar to a series of levades with a forward motion (not in place), with the horse gradually bringing its legs further under himself in each successive movement and lightly touching the ground with his front legs before pushing up again.

Superb dressage turn-out, with braided mane, banged and pulled tail, trimmed legs and polished hooves. Rider wears a shadbelly and top hat, white gloves, tall boots, and spurs

Tack and dressage

Dressage horses are shown in minimal tack. They are not permitted to wear boots (including hoof boots) or wraps (including tail bandages) in competition, nor are they allowed to wear martingales or training devices. Due to the formality of dressage, tack is usually black, although dark brown is seen from time to time.

An English-style saddle is the preferred piece of tack for riding dressage. It is designed with a long and straight saddle flap, mirroring the leg of the dressage rider, which is long with a slight bend in the knee. The dressage saddle usually has a deeper seat than a jumping saddle, to help hold the rider in a deep seat. However, many dressage masters shun the deep seat, believing that a rider should not need the saddle to help them stay in place. The saddle is usually placed over a square, white saddle pad. A dressage saddle is required in FEI classes.

At the lower levels of dressage, a bridle should use a plain cavesson, drop noseband, or flash noseband. As of 2006, drop nosebands are relatively uncommon, with the flash more common. At the higher levels, the flash and drop are not used, and a plain cavesson or a crank noseband is permitted.

The dressage horse is only permitted to use a mild snaffle bit, and the rules regarding bitting vary from organization to organization. The loose-ring snaffle with a mild single- or double-joint is most commonly seen. Upper level dressage horses are ridden in a double bridle, using both a mild bradoon and a stronger curb bit.

Turn-out of the dressage horse

Dressage horses are turned out to a very high standard, as competitive dressage is descended from royal presentations in Europe. It is traditional for horses to have their mane braided. In eventing, the mane is always braided on the right. In competitive dressage, however, it is occasionally braided on the left, should it naturally fall there. Braids vary in size depending on the conformation of the horse, but Europeans tend to put in fewer, larger braids, while horses in the United States usually have more braids per horse (possibly from the influence of hunter-style riding in the country). Braids are occasionally accented in white tape, which also helps them stay in throughout the day. The forelock may be left unbraided; this style is most commonly seen on stallions.

Horses are not permitted to have bangles, ribbons, or other decorations in their mane or tail. Tail extensions are permitted in the United States.

The tail is usually not braided (although it is permitted), because it may cause the horse to carry the tail stiffly. Because the tail is an extension of the animal's back, a supple tail is desirable as it shows the horse is supple through his back. The tail should be "banged," or cut straight across (usually above the fetlocks but below the hocks when held at the point where the horse naturally carries it). The dock is pulled or trimmed to shape it and give the horse a cleaner appearance.

The bridle path is clipped or pulled, usually only 1-2 inches. The animal may or may not be trimmed. American stables almost always trim the muzzle, face, ears, and legs, while European stables do not have such a strict tradition, and may leave different parts untrimmed.

Hoof polish is usually applied before the horse enters the arena. The horse should be incredibly clean, with a bathed coat and sparkling white markings. Foam should not be cleaned off the horse's mouth before he enters the arena.

Quarter marks are sometimes seen, especially in the dressage phase of eventing, however they are not currently in style for competitive dressage. The rider's clothing

Dressage riders, like their horses, are dressed for formality. In competition, they wear white breeches, that are usually full-seat to help them "stick" in the saddle, with a belt, and a white shirt and stock tie with a gold pin. Gloves are usually white, although less-experienced riders or those at the lower levels often opt for black, as their hand movement will not be as noticeable. The coat worn is usually solid black, although solid navy is also occasionally seen. For upper-level classes, the rider should use a shadbelly, rather than a plain dressage coat.

Riders usually wear tall dress boots, although field boots may be worn at the lower levels. Spurs are required to be worn at the upper-levels. Double Bridles are also required at the FEI levels.

If the dressage rider has long hair, it is typically worn in a hair net. Lower-level riders may use a hunt cap, or helmet with a safety harness. Upper-level riders are required to wear a more formal top hat, matching their coat.

LINKS

A - Z SPORTS INDEX

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|

||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2020. The bird logo and name Solar Navigator are trademarks. All rights reserved. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity. |