|

WHALING - DOLPHINS | SHARKS | WHALES

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Whaling is the hunting of whales for food, oil, or both. The hunting of whales by Eskimos and Native Americans began around 100 a.d. in North America. In Europe the systematic hunting of whales began during the Middle Ages and greatly expanded in the seventeenth century. Whaling was driven by the desire to procure whale oil and sperm oil. Whale oil comes from baleen whales and is an edible product that was used in the making of margarine and cooking oil. Sperm oil, which comes from sperm whales, was used for illuminating lamps, as an industrial lubricant, and as a component of soaps, cosmetics, and perfumes.

During the nineteenth century, the U.S. whaling fleet dominated the world industry. Most of the seven hundred U.S. ships sailed out of New Bedford and Nantucket, Massachusetts. However, the industry went into a steep decline with the discovery and exploitation of petroleum during the late nineteenth century. Though new uses for sperm oil were developed, the U.S. fleet gradually disappeared.

In the early twentieth century, concerns were raised about the dwindling whale population. An international movement to regulate the hunting of whales met resistance from Scandinavian countries and Japan, but in 1931 the League of Nations Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was convened. The convention proved unsuccessful because several important whaling states refused to participate.

Annual international whaling conferences led to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling in 1946, which established the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The IWC was charged with the conservation of whale stocks. It limited the annual Antarctic kill and created closed areas and hunting seasons throughout the world. Despite these initiatives and others over the years, the whale population edged closer to extinction, and the IWC agreed in 1982 to prohibit commercial whaling beginning in 1986. Commercial whaling has continued, however, often under the fiction of capturing specimens for scientific research.

In 1990 a scientific study was begun to determine if the whaling moratorium should be lifted. Though the study indicated that whale populations were growing, in 1993 the United States refused to agree to a resumption of commercial whaling, and the IWC agreed. The United States warned that if a country (primarily Japan, Norway, or Iceland) ignored the IWC conservation program and resumed commercial whaling without IWC approval, that country's actions would be reviewed, and sanctions would be considered where appropriate.

EARLY WHALING

Whaling for subsistence dates to prehistoric times. The early people of Korea were hunting whales as far back as 5000 B.C., and those of Norway began whaling at least 4,000 years ago. Various peoples of the NW North American coast and the Arctic have a long tradition of whaling. Whaling, done from canoes or skin boats, often when migrating pods of whales passed nearby, was a very dangerous undertaking. Over time, many, such as the Qwidicca-atx (Makah) people of the Olympic peninsula, developed set spiritual and hunting practices that became the core of their culture.

Crew of oceanographic research vessel "Princesse Alice," of Albert Grimaldi (later Prince Albert I of Monaco) pose during flensing

Early Commercial Whaling

The hunting of whales is thought to have been pursued by the Basques from land as early as the 10th cent. and in Newfoundland waters by the 14th cent. It is not until the middle of the 16th cent., however, that the appearance of Basques in those waters is established by record. Whaling on a large scale was first organized at Spitsbergen at the beginning of the 17th cent., largely by the Dutch who, with the Basques, apparently developed methods of flensing and boiling. The Dutch were at first in competition with the English Muscovy Company of London, but before its collapse in 1625 they had gained ascendancy; in 1623 they established the port of Smeerenberg. Large profits continued only until c.1640, when the scarcity of whales forced the Dutch farther out into the northern waters in search of them.

By the middle of the 17th cent. whaling from the land was established in America. Its centers, at first on Long Island and Cape Cod, shifted to Nantucket and then New Bedford, Mass., the greatest whaling port in the world until the decline (c.1850) of the industry. With the capture (1712) of a sperm whale by a Nantucket fisherman, the superior qualities of sperm oil were discovered, and American whalers began fishing farther south in search of the sperm whale, which superseded right whales in value.

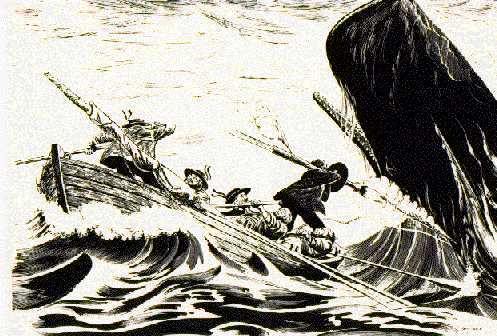

The American fisheries were set back by the American Revolution, but in 1791 the first Americans rounded Cape Horn to hunt in the S Pacific. Another, but temporary, setback occurred in the War of 1812, but the outcome spelled the complete defeat of British whaling, and from 1820 until shortly before the Civil War, Americans sailed the Pacific from south to north, on voyages often lasting as long as three or four years, in search of whales. Melville's Moby-Dick gives an account of a voyage in this period. The advent of the Civil War, together with a decrease in the demand for sperm oil and in the number of whales, brought the decline of the industry.

Modern Whaling

The invention (c.1856), by the Norwegian Sven Foyn, of a harpoon containing an explosive head may be said to have inaugurated modern whaling. Besides insuring the whale's immediate death this type of harpoon was subsequently modified to shoot compressed air into the whale so that it will not sink before it can be secured. The development of the factory ship, equipped to take on board and completely process whales caught by smaller chaser boats, increased safety and enhanced the ability to catch the larger blue whale. It also allowed for the use of all parts of the whale; formerly only the blubber and head could be procured, and the job of flensing from the side of the ship was a hazardous one.

In 1904 operations commenced from a whaling station on South Georgia, an island in the S Atlantic, and the modern industry found in Antarctic waters the last rich whaling fields on the globe. The number of expeditions from the Antarctic islands, however, was restricted by Great Britain, which had secured sovereignty over these areas. In 1925 the first floating factory was sent to the Antarctic regions; that innovation led to the greatest expansion in the history of whaling. In 1930 the modern whaling industry reached its zenith, with 6 shore stations, 41 floating factories, and 232 whale catchers in the Antarctic regions, of which 3 stations, 27 factory ships, and 147 catchers were Norwegian and 2 stations, 27 floating factories, and 68 catchers were British. During World War II most of the world's whaling fleet was lost, but afterward Norway, Britain, and Japan (which had started Antarctic expeditions in 1935) soon reestablished their prewar positions, and in addition the Soviet Union, the Netherlands, and South Africa appeared in the Antarctic regions for the first time.

Whaling in Alaska

Attempts at Regulation and Protection

In 1932–33, partly in response to the collapse of the whale-oil market, the first attempts were made to regulate and restrict the catch by international agreement. After World War II the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was formed in Washington, D.C., by 17 nations, including all those operating in the Antarctic regions. The commission, which regulates most of the world's whaling activity, began in the 1960s to limit the number and species of whales that could be hunted. In the subsequent years, environmental activist groups, notably Greenpeace, became extremely involved in the attempt to stop whaling, and in 1982 the IWC voted a moratorium on commercial whaling, to take effect after the 1984–85 season. Exceptions to the moratorium generally have been made for native peoples, such as the Makah, who traditionally had hunted whales and used their meat as a major part of their diet. These regulations are not adhered to by all nations, including some members of the commission (which now has 61 member nations), and whales continue to be hunted by Norway and, for research purposes, by Japan and Iceland. (The killing of whales for research, while permitted under IWC regulations, is opposed by many as unnecessary, and opponents of whaling believe it has been abused and should be abolished.) In 2003 the IWC voted to expand its main functions to include whale conservation. The Indian Ocean and the ocean waters off Mexico, a number of South Pacific island nations and territories, and Antarctica have been designated whale sanctuaries. The protective efforts have allowed some species to return to numbers that will probably assure their survival, but others, especially the right whales, remain severely depleted in numbers and endangered.

Historically, poor conservation management by many nations led to far more whales being killed than could be sustained and to near extinction of several species. Modern whaling methods involve firing a harpoon near the head of the animal. An explosive charge inside the harpoon then explodes beneath the whale's skin, killing it.

International cooperation on whaling regulation started in 1931 and a number of bi- and multi-lateral agreements now exist in this area, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) of 1946 being the most important. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was founded by the ICRW for the purpose of giving management advice to the member nations on the basis of the work of the Scientific Committee.

The members of the IWC voted in 1982 to enter into a moratorium on all commercial whaling beginning in the 1985-86 season. Since 1992, the IWC Scientific Committee has requested of the IWC that it be allowed to give quota proposals for some whale stocks, but this has so far been refused by the IWC. Norway legitimately continues to hunt Minke Whales commercially, as it lodged an objection to the moratorium.

The history of whaling

Humans have hunted whales since time immemorial. The oldest records of whale hunts are rock carvings found in South Korea that date back to 6000 BC. Since that time, whalers have grown ever more technically sophisticated. Historical whaling can be divided into six main stages, some of them overlapping:

Modern Whaling

Although whale oil has little commercial value today, whale meat has come to be considered a delicacy, particularly in Japan and Norway (though up to the 1980's, whale meat was considered to be inferior to beef in Norway.) The primary species hunted today is the Minke Whale, the smallest of the baleen whales. Recent scientific surveys estimate a population of 180,000 in the central and North East Atlantic and 700,000 around Antarctica. International Whaling Commission

Modern whaling is regulated by the International Whaling Commission, set up in 1946 by the United Nations International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. On July 23, 1982 the IWC members voted to impose an open-ended moratorium on commercial whaling. Article V(3) gives states a 90-day period to object to decisions taken by the commission. Norway did object to the decision and further regards it as ultra vires (i.e. null and void), since the decision was not based on advice from the Scientific Committee and is, they say, in contradiction with the purposes set forth in the preamble of ICRW. Norway was thus able to continue a commercial hunt if it wished, and has done so since 1993.

In 2003, the IWC began a multi-year survey in Antarctic waters to update current population estimates. Norway has been conducting multi-year surveys each year since 1995 as required by their membership in the IWC. However several governments influential in the IWC, in particular those of Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have hardened their opposition to whaling in recent years and may continue to attempt to block proposals from pro-whaling nations for a commercial catch regardless of the results of these surveys.

In addition to Norway's commercial whaling, IWC regulations allow for two further types of whaling: whaling for the purposes of scientific research, and subsistence whaling in aboriginal communities. These are described further below.

The IWC only has jurisdiction over the large cetaceans such as, the blue whale, bowhead, humpback, gray and sperm whale. Only countries that are members of IWC are bound by the rules of IWC.

Research whaling

Article VIII of the International Convention on the Regulation of Whaling states

Japanese and Icelandic whaling is carried out under the auspices of this Article.

Aboriginal subsistence whaling

Alongside commercial whaling and whaling for research, a third type of whaling is recognised by the IWC. This third type of whaling, called aboriginal subsistence whaling, is allowed under the terms of the whaling moratorium if an aboriginial group has a tradition and culture of whaling. The IWC says that such whaling must

The countries which practice aboriginal subsistence whaling are Denmark (Greenlandic Inuit), Russia (Siberian groups), St. Vincent and the Grenadines (one man) and the United States (Alaskan Inuit). Canadian Inuit also carry out whaling, though Canada is not a member of the IWC. Both animal rights groups and some pro-whaling nations (such as Japan) say that not all whaling carried out in the name of subsistence, is actually for that purpose.

Japan says that recognising these aboriginal claims but not the claims of Japanese groups with an ancient history of whaling is inconsistent and indeed "racist". For full details see the Aboriginal whaling article.

Whaling nations

Faroe Islands

Around one thousand Long-finned Pilot Whales are killed in the annual whale "grind" by Faroese fisherman each year. The current practice continues a tradition going back to the tenth century. However anti-whaling campaigners campaign particularly vociferously against Faroese whaling - saying that the method of killing is cruel. For a full discussion see Whaling in the Faroe Islands.

Iceland

Iceland has a long tradition of subsistence whaling. Indeed whaling of one form or another has been conducted from the island since it became populated more than eleven hundred years ago. The early reliance of whales is reflected in the Icelandic language - hvalreki is the word for both "beached whale" and "jackpot".

Iceland allowed Norwegian whalers to set up thirteen whaling stations around the island in 1883. By 1915, 17,000 whales had been taken from Icelandic waters, eradicating Northern Right Whales and Gray Whales in the area. The Icelandic Government banned whaling in its waters to allow time for population recovery. The law was repealed in 1928.

By 1935 Icelanders had set up their own commercial whaling operation for the first time. They hunted mostly Sei, Fin and Minke Whales. In the early years of this operation Blue, Sperm and Humpback Whales were also hunted, but this was soon prohibited due to decimated numbers. Between 1935 and 1985 Icelandic whalers killed around 20,000 animals in total. Unlike Norway, Iceland did not protest against the IWC moratorium and was therefore limited to whaling conducted under the name of scientific research. Between 1986 and 1989 around 60 animals per year were taken. However under strong pressure from the international community, not convinced that the kills were truly for scientific purposes (particularly because the meat was sold to Japan) Iceland ceased whaling altogether in 1989. Following the 1991 refusal of the IWC to accept its Scientific Committees recommendation to allow limited whaling, Iceland left the IWC.

With significant support from its people, Iceland rejoined the IWC in 2002. This allowed it to restart a program of whaling in the summer of 2003. Iceland presented a feasibility study to the 2003 IWC meeting to take 100 Minke Whales, 100 Fin Whales and 50 Sei Whales in each of 2003 and 2004. The primary aim of the study was to deepen the understanding of fish-whale interactions - the strongest advocates for a resumed hunt are fisherman concerned that whales are taking too many fish. The hunt was supported by three-quarters of the Icelandic population. Amid concern from the IWC Scientific Committee about the value of the research and its relevance to IWC objectives no decision on the proposal was reached. However under the terms of the convention the Icelandic government issued permits for a scientific catch. In 2003 Iceland took 36 Minke Whales from a quota of 38. In 2004 it took 25 whales (the full quota). In 2005, the government issued a permit for a third successive year - allowing whalers to take up to 39 whales.

A dish of whale meat in JapanJapan

Harpooning of whales by hand began in Japan in the 12th century, but it was not until the 1670s, when a new method of catching whales using nets was developed, that whaling really began to spread throughout Japan. In the 1890s Japan followed international trends, first switching to modern harpoon whaling techniques, and eventually to factory ships for mass whaling. In the postwar 1940s and 1950s, whale meat became a primary source of food and protein in Japan following the famines that came with World War II. In many whaling nations, the discovery of petroleum products that could replace the industrially important parts of whales, such as the oil, resulted in a decline in the importance and levels of whaling. This was not the case in Japan, however, where whale meat was an important source of food, and where the whaling industry was a source of pride in a country that is dependent on food importation to feed its populace.

When the commercial whaling moratorium was introduced by the IWC in 1982, Japan lodged an official objection, but withdrew this objection in 1987 after the United States threatened it with sanctions. Thus Japan became bound by the moratorium, unlike Norway, Russia and (more disputed) Iceland. Therefore, in 1987, Japan stopped commercial whaling activities in Antarctic waters, but in the same year began a controversial scientific whaling program (JARPA - Japanese Research Program in Antarctica).

The Japanese government mainly justifies this type of whaling on the grounds that analysis of stomach contents provides insight into the dietary habits of whales, and that analysis of actual tissue is the only way to ascertain the age of a whale as well as the degree of interbreeding in the population which provides vital insight into whale population distribution.

Japan's scientific whaling program has remained controversial, with conservation groups and anti-whaling countries such as the US and Australia maintaining that the number of animals killed is much greater than demanded by scientific purposes, and that the real reason for the scientific kills is to provide whale meat for Japanese restaurants and supermarkets. The Japanese government points out that IWC regulations require that whale meat be utilised upon the completion of research. The Japanese government insists that it be allowed to continue research into whale populations and breeding habits in order to refute claims that commercial whaling threatens the sustainability of the populations.

In 1994, Australia attempted to stop some of the Japanese whaling program by enforcing a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the Australian Antarctic Territory. However, antarctic territories are not generally recognized internationally. In particular, the Antarctic Treaty, to which Australia is a signatory, specifically states that all claims to antarctic territories remain unresolved while the treaty is in force. (The treaty was originally devised to prevent conflict between the USSR and USA during the cold war.) Legal advice obtained by the Australian government indicated that attempts to stop Japanese whaling in the Australian Antarctic Territory by resorting to international courts may, in fact, have led to Australia losing its claim to that territory.

In 2002, Japanese whalers took 5 Sperm, 39 Sei, 50 Bryde's and 150 Minke Whales in the northern catch area and 440 Minke Whales in the southern catchment area. The catch was carried out under the IWC's special licence for whaling research.

Total numbers for the 2004-2005 whaling season were 441 minke whales ( SH area pelagic ) 100 minke whales ( NP area pelagic ) and 60 minke whales in coastal regions of Japan. 3 sperm whales and 51 Bryde´s whales were also taken ( pelagic ) during this period bringing the total number of whales in the 2004/05 season to 780 ( Source IWC official figures )

In 2005, the JARPA scientific research program was replaced by the JARPA-II program, which increases the quota of Minke whales to 900, and more controversially, adds Fin whales to the program, with a quota of 10 animals in 2005. This move has sparked a great deal of controversy among anti-whaling nations, in particular because fin whales are listed as endangered under the Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species. From 2007, Japan plans to start taking up to 50 humpback whales and 50 fin whales annually.

Refer to International Whaling Commission for more details on controversy surrounding the Japanese whaling program.

Norway

Norway has registered an objection to the International Whaling Commission moratorium, and is thus not bound by it. In 1993 Norway, as the only country in the world, resumed a commercial catch, following a period of five years where a small catch was made under a scientific permit. The catch is made solely from the North-east Atlantic Minke Whale population, which is estimated to consist of about 110,000 animals. Norwegian minke whale catches have fluctuated between 503 animals in 1997 to 639 in 2005.

(Sources: Most sources quote the High North Alliance, a pro-whaling lobby operated by Norwegian whalers. Quotas are set by the Norwegian government).

Prior to the moratorium, Norway caught around 2,000 Minkes per year. The North Atlantic hunt is divided into five areas and usually lasts from early May to late August. Norway exports a limited amount of whale meat to the Faroes and Iceland. It has been attempting to export to Japan for several years, though this has been hampered by legal protests and concerns in the Japanese domestic market about the effects of pollution on Atlantic whales.

In May 2004 the Norwegian Parliament passed a resolution to considerably increase the number of Minkes hunted each year - up to 1,800 animals per year by 2006. The move would have to be agreed to the fisheries ministry that sets the quota. The fisheries ministry also proposed a satellite tracking programme to monitor numbers of other species as possible prelude to resuming hunting of them. Commenting on this proposal Rune Frovik of the High North Alliance said "The proposal appears to apply in principle to virtually any species except Bowheads and Blue Whales, though in practice the government appears to be most interested in assessing stocks of Fins, Humpbacks, pilot whales and several dolphins."

References: BBC report on Norwegian Parliament proposals

The arguments for and against whaling

Conservation status

The sharpest point of debate over whaling today concerns the conservation status of hunted species. Today there is widespread agreement around the world that it is morally wrong to exterminate a species of animal for food. The past mismanagement of whale stocks has depeleted the overall whale population to a significant extent and four species of whale are still endangered. As the graph to the right indicates, the conservation status of whales are strongly correlated with the past hunt. Thus it is unlikely, for instance, that the Blue Whale will be hunted again for the foreseeable future because its population levels have remained stagnant since the hunting ban on them in the 1960s.

Other species on the other hand, in particular the Minke Whale, have never been considered endangered and still other species have shown signs of recovery. It is these species of whales that whalers wish to hunt commercially, believing that with modern techniques a hunt of these species could be sustained without damage to the ecosystem.

It is widely held belief in pro whaling countries that conservation is a mere excuse used by anti whaling side whose stance largely originate from cultural rather than scientifice reasoning. Recent move by anti whaling groups to diversify their anti whaling argument has been taken as confirmation of this suspicion.

Still those opposed to whaling argue that a return to full-scale commercial whaling will lead to economic concerns overriding those of conservation, there is a continuing battle between each side as to how to describe the current state of each species. For instance, conservationists are pleased that the Sei Whale continues to be listed as endangered but Japan says that the species has swelled in number from 9,000 in 1978 to about 28,000 in 2002 and so its catch of 50 Sei Whales per year is safe, and that the classification of endangered should be reconsidered for the north Pacific population.

A complete list of whale conservation statuses as listed by the IUCN is given below. Note that, in the case of the Blue and Gray Whales, the IUCN distinguishes the statuses of various populations. These populations, whilst not regarded as separate species, are considered sufficiently genetically different to warrant conserving each.

Anti-whaling side argue that there are further considerations outside of the mere number of specimens required for the species to survive involve the whale's position as pinnacle in the food chain. What effect they have on the ocean's system is not fully known. As little as 10 years ago was it first discovered how whales sleep (vertically). In a BBC documentary 'Blue Planet', a small glimpse was seen of the whale's impact as a source of food. The corpse of a whale feeds large numbers of fish, in the thousands, from groups of sharks to small bottom feeders, lasting from several months to a year. Pro-whaling side consider this argument to be spurious as whale corpse is large simply because they consume proportionately large resource hence whale corpse providing no extra input into food chain. And there is no indication that whale corpse is somewhat "essential" in comparison to corpse of any other sea creature.

Additionally the IUCN notes that the Atlantic population of Gray Whales was made extinct early around the turn of the eighteenth century.

Organic growth; Method of killing

Farming whales in captivity has never been attempted and would almost certainly be logistically impossible. Thus unlike the farming of many animals, whale meat is grown entirely organically. However whales are killed using explosive harpoons, which puncture the skin of the whale and then explode inside the body. Anti-whaling campaigners say this method of killing is cruel, particularly if carried out by inexperienced gunners because the whale can take several minutes or even hours to die. In March 2004, Whalewatch, an umbrella group of 140 conservation and animal welfare groups from 55 countries published a report, Troubled Waters, whose main conclusion was that whales cannot be guaranteed to be killed humanely and that all whaling should be stopped. They quoted figures that said 20% of Norwegian and 60% of Japanese-killed whales failed to die as soon as they had been harpooned. John Opdahl of the Norwegian embassy in London responded by saying that Norwegian authorities worked with the IWC to develop the most humane killing methods. He said that the average time taken for a whale to die having been shot was the same as or less than those animals killed by big game hunters on safari. Whalers also say that this free roaming lifestyle followed by a quick death is less cruel than the long-term suffering of battery farmed animals also used to provide food.

Whaling harpoon canon

The pro-whaling High North Alliance points to apparent inconsistencies in the policies of some anti-whaling nations. For instance, the United Kingdom allows the commercial shooting of deer without these shoots adhering to the standards of British slaughterhouses, but says that whalers must meet these standards as a pre-condition before they would support whaling. A High North article on the issue Moreover, hunting or fox hunting where fox are mauled by dogs are legal in many anti whaling countires. This inconsistency is used to argue that whale are equivelant of cow in India and cruelty argument is mere expression of cultural bigotry, similar to Western attitude toward eating of dog meat in several East Asian countries.

The economic argument

Anti whaling side argue that the whales that are killed are those that are most curious about boats and thus the easiest to approach and kill. However these individuals are also the most valuable to the whale-watching industry in coastal areas, as these "friendly" whales easiest means of providing an experience to their customers. The argument over whether whales are worth more dead than alive is complex and unresolved. The whale-watching industry, and those opposed to whaling on moral grounds, claim that once all benefits to local economies such as hotels, restaurants and other tourist amenities are factored in, and the fact that a whale can only be killed once but watched many times, the economic balance weighs firmly down on the side of not hunting whales. This economic argument is a particular bone of contention in Iceland, which has amongst the most-developed whale-watching operations in the world and where hunting of Minke Whales began again in August 2003. The argument is less applicable to the Antarctic waters, where Japan wishes to hunt as Minke Whales are more abundant there and there are far fewer whale-watching cruises. Many developing countries such as Brazil, Argentina and South Africa argue that whalewatching, a growing billion-dollar industry, provides more revenue and more equitable distribution of profits than the possible resumption of commercial whaling by pelagic fleets from faraway developed countries. These countries are defending their right to the non-lethal use of whale resources and refuse to bow to the pressures of the whaling industry to allow the resumption of commercial whaling in their regions. Aside from Indonesia, no country in the Southern Hemisphere is currently whaling or intends to, and proposals to permanently forbid whaling South of the Equator are defended by the abovementioned developing countries plus Peru, Uruguay, Australia, and New Zealand, which strongly object to the continuation of Japanese whaling in the Antarctic.

Pro whaling side consider that the entire debate is fictitious on the ground that the debate covertly imply that hunt is done on unsustainable basis. This is obviously not the argument of whalers. If whale is hunted on sustainable basis, the entire context of debate proposed by anti whaling side that whale watching industry and whaling industry is in competition is invalid. Therefore, the pro whaling side consider that the context of the debate itself is slanted toward anti-whaling argument. Whales are the largest animals in the world, a single whale kill provides more meat than with any other animal. Whaling and its associated activities continue to provide employment and economic stimulant for fishery, logistic, restaurant and other related industries in developed countries. Whale watching industry also has significant economic benefit and pro whaling side has no objection to the whale watching industry..

Intelligence

The issue of the extent of cetacean intelligence is also debated mainly by anti whaling side because some advocate believe that whale's intelligence is somewhat equal or close to human. No scientist ever claim that whale is equally intellgient to human though number of research show that whale are capable of certain behaviour which are often associated with human. Obviously, no non human mammals has ever displayed intelligence equal to full capability of ordinary human.

Most of the research on cetacean intelligence has consisted of behavioral inference tests carried out on dolphins. For example, Bottlenose Dolphins are able to recognize their images in a mirror; however, in other research, they scored lower than ferrets in a test of learning set formation. Generally, both dolphin and pig intelligence is rated as higher than that of dogs. On the other hand, it is nearly impossible to duplicate these types of tests for whales.

Anti-whaling campaigners and nations say that, still, cetaceans are amongst the most intelligent of all non-humans and thus it is morally wrong to kill them for food. However, those in favour of whaling point out that pigs are also amongst the most intelligent of mammals and say that it thus inconsistent to claim that pigs can be used for food, and whales not, other considerations notwithstanding. There is no scientific study which categorically state that whale are more intelligent than pig. Thus, in the view of pro-whalers, if the eating of other somewhat "intelligent" land animal is non issue, eating of whales should not be rejected on the ground of intelligence. This leave legally enforced vegetarianism as the only logically consistent option, which is not adovocated by anti whaling side.

Fishing

Whalers say that whaling is an essential condition for the successful operation of commercial fisheries, and thus plentiful availability of food from the sea that consumers have become accustomed to. This argument is made particularly forcefully in Atlantic fisheries, for example the cod-capelin system in the Barents Sea. A Minke Whale eats 10 kg fish meat per kg, which puts a heavy predation pressure on commercial species directly or indirectly. Thus whalers say that an annual cull of whales is needed in order that fish be available for humans. Anti-whaling campaigners say that the pro-whaling argument is inconsistent: If the catch of whales is small enough not to impact overall whale numbers, it is also too small to affect fish numbers. Thus to make more fish available, they say, more whales will have to be killed to put populations at risk. The whalers argue that the purpose of culling is to keep populations in check, not to put populations at risk.

Professor Daniel Pauly and Director of the Fisheries Centre at the University of British Columbia weighed into the debate in July 2004 when he presented a paper to the 2004 meeting of the IWC in Sorrento. Pauly's primary research is investigating the reasons for the decline in fish stocks in the Atlantic, under the auspices of the Sea Around Us Project. However this report was commissioned by the Humane Society International, one of anti-whaling lobbies. The report says that although cetaceans and pinnipeds are estimated to eat 600m tonnes of food per year, compared with just 150m tonnes eaten by humans (*), the type much of the food that cetaceans eat (in particular deep sea squid and krill) is not eaten by human. Moreover, the reports says, the locations where whales and humans catch fish only overlap to a small degree. In an interview with the BBC Pauly said "The bottom line is that humans and marine mammals can co-exist. There's no need to wage war on them in order to have fish to catch. And there's certainly no cause to blame them for the collapse of the fisheries. It's really cynical and irresponsible for Japan to claim that the developing countries would benefit from a cull of marine mammals. It's the rich countries that are sucking the fish out of the poor countries' own seas." In the report Pauly also considers more indirect effects of whale eating on the availability of fish for fisheries. He continues to conclude that whales are not a significant reason for diminish fish stocks.

However, the dietary behaviour of whales differ among species as well as season, location and availability of prey. For example, Sperm Whales's prey species are in general dominated by mesopelagetic squid. However, in Iceland, they are reported to consume mainly fish (Sigurjónsson, et al 1998). Minke Whales are known to eat wide range of species including krill, capeline, herring, sand lance, mackerel, but gadoids, cod, saithe and haddock (Haug et al, 1996). Minke Whales are estimated to consume 633,000 tons of Atlantic herring per year in part of Northeast Atlantic (Folkow et al, 1997). Net loss of five tonnes of cod and herring fishery per an extra minke whale are estimated to result in Barents Seas. (Schweder, et al, 2000)

(*) These are Pauly's figures. Researchers at the Institute for Cetacean Research gave figures of 90m tonnes for humans and 249-436m tonnes for cetaceans. Reference [3]

References

External links and further reading

Bibliography

See J. T. Travis, A History of the Whale Fisheries (1921); C. Ashley, The Yankee Whaler (1926, 2d ed. 1942); A. Church, Whale Ships and Whaling (1938); F. R. Dulles, Lowered Boats: A Chronicle of American Whaling (1933); E. Stackpole, The Sea-Hunters: The New England Whaleman...1635–1835 (1953); F. Crisp, The Adventure of Whaling (1954); A. Whipple, Yankee Whalers in the South Seas (1954); E. Ash, Whaler's Eye (1962); L. H. Matthews et al., The Whale (1968); G. L. Small, The Blue Whale (1971); J. N. Tennessen and A. Johnsen, The History of Modern Whaling (tr. 1982); D. Day, The Whale War (1987). See also IWC, The Journal of Cetacean Research and Management (1999–).

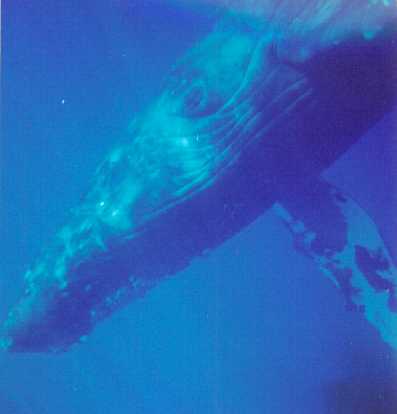

HUMPBACK WHALE

The Elizabeth Swann, autonomous solar and wind powered boat

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This

website is copyright © 1991- 2020 Electrick Publications. All rights

reserved. The bird logo

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||