|

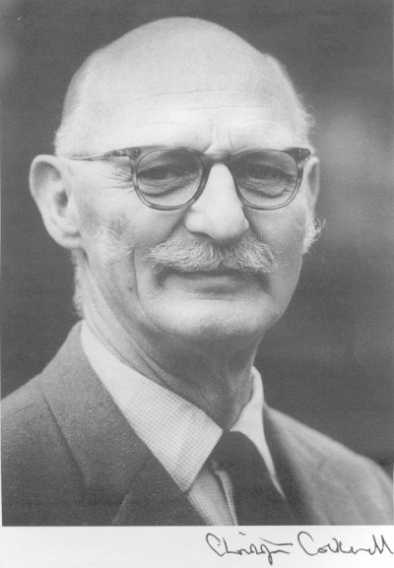

SIR CHRISTOPHER COCKERELL

|

|||

|

Sir Christopher Sydney Cockerell (June 4, 1910 – June 1, 1999) was a British engineer, inventor of the hovercraft. Cockerell was born in Cambridge, England, in a house called "Wayside" in Cavendish Avenue, where his father, Sir Sydney Cockerell, was curator of the Fitzwilliam Museum. He was educated at Gresham's School, Holt, Norfolk. He then studied engineering at Peterhouse, Cambridge. His father, sometime private secretary to Sir William Morris and from 1908 to 1937 Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

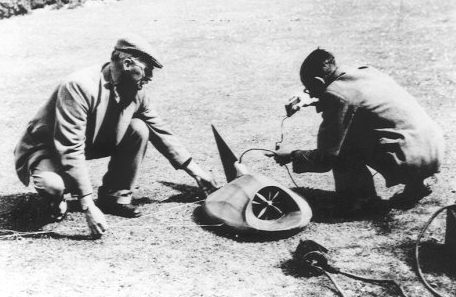

Sir Christopher Sydney Cockerell and his (Lyons coffee) tin can experiment

The Cockerells were a talented family. The sons of Sydney John Cockerell, a London coal merchant, and Alice neé Bennett, the daughter of a City Watchmaker, Sir Sydney’s elder brother, Theodore, was a biologist, his younger brother, Douglas, an eminent bookbinder; while Douglas’s son Sydney Maurice (‘Sandy’), two years Christopher’s senior and also a bookbinder, was a celebrated and innovative designer of marbled papers.

In his youth he was always tinkering and inventing, much to the dismay of his father, whose interests were literary, not mechanical.

He began his career working for the Marconi company in 1935 where he received three dozen patents, and got married soon afterwards. He worked on radar systems during the Second World War. His great invention, the hovercraft, first saw the light of day in 1953. The idea was not an immediate success, and he was forced to sell personal possessions in order to finance his research. By 1959, a prototype craft was crossing the English Channel between Dover and Calais. Cockerell was knighted in 1969 for his services to engineering.

INVENTION - A popular and fast way to get from Portsmouth to the Isle of Wight was by the Hoverspeed service. Hoverspeed eventually moved from hovercraft into high speed ferries, presumably because the operating costs of such technological marvels was too high. In order to be able to schedule commercial services, the hover craft concept of Christopher Cockerell had to be perfected. The patent declared a secret by the Ministry of Supply, hence preventing disclosure, Cockerell had to wait until 1957 when he heard of a similar invention being developed that overcame military objections, after which he managed to secure funding to develop his invention. The first prototype crossed the English Channel in 1959.

The theory behind one of the most successful inventions of the 20th century, the Hovercraft, was originally tested in 1955 using an empty cat food tin inside a coffee tin, an industrial air blower and a pair of kitchen scales.

Christopher Cockerell was initially testing out the idea that it was possible to produce a cushion of air between the bottom of the tins and the surface of the scales. Once he had established that this was possible he decided to experiment with more sophisticated models. Although his first tests were carried out on dry land his main aim was to prove that drag or friction between boats and water could be substantially reduced if the ‘craft’ floated on an air cushion. And so the ‘hovercraft’ came in to being. Indeed Cockerell came up with the word too, which was recently chosen to represent 1959 in the 100 words, which encapsulate the 20th century for the millennium edition of the Collins English Dictionary.

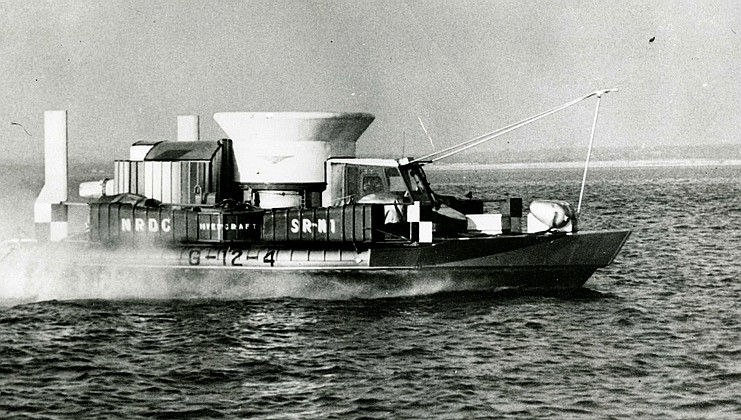

Crossing the English Channel on a cushion air for the first time

Despite an interest in the arts, Christopher read Engineering at Peterhouse, Cambridge. After Cambridge he worked for the Radio Research Company until 1935 and then for the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company from 1935 until 1951.

He had an enormous capacity for invention and his father, despite reservations (he once described his son as ‘no better than a garage hand’), put up the money for his early patents. (When Sir Sydney died in 1962, aged 94, some obituaries of this great museum director and manuscript collector, friend of Bernard Shaw and T.E. Lawrence, literary executor of Thomas hardy, called him simply ‘grandfather of the hovercraft’).

During the war years Cockerell worked with an elite team at Marconi to develop radar, a development which Churchill believed had a significant effect on the outcome of the Second World War, and Cockerell believed to be one of his greatest achievements. Whilst at Marconi Cockerell patented 36 of his ideas.

Cockerell left Marconi in 1950, and with a legacy left by his beloved wife Margaret’s father, he and Margaret were able to purchase a small boatyard in Norfolk. This never seemed to make money and Cockerell’s mind turned back to earlier ideas.

He decided to use larger models on water. Initial experiments convinced Cockerell that boats could be made to float on a cushion of air, thus reducing the effect of the water drag. After many trials he successfully designed a craft which proved his ideas were correct. He was not surprised. The modified punt he used had a special pump to blow high-pressure air down under and around the rim of the craft. A strong rubber curtain retained most of the air, hence creating lift.

Cockerell had set up a company, Ripplecraft, to develop his ideas further and in 1955 he eventually convinced the Ministry of Supply to back his project. He had a hard time trying to convince the military: the Admiralty said it was a plane not a boat; the RAF said it was a boat not a plane; and the Army were ‘plain not interested’. The irony is that it has been the Marines who have taken the hovercraft most seriously, with over 100 giant craft now in use in America and 250 in the Soviet Union, many used in recent conflicts.

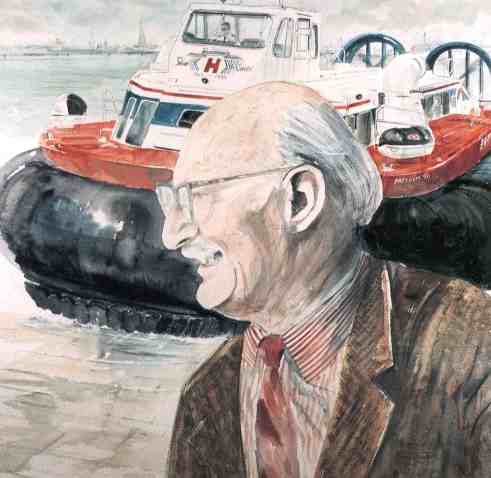

Sir Christopher Cockerell (left) and helper testing concept (middle) and hovercraft portrait (right)

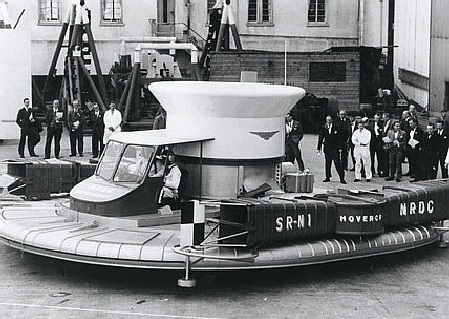

In these early days Cockerell’s idea was patented and immediately put on the secret list. Nothing happened and Cockerell became increasingly agitated. Eventually, in 1958, after declassification, the National Research Development Council (NRDC) funded the design and construction of SR.N1 – the world’s first man-carrying amphibious hovercraft.

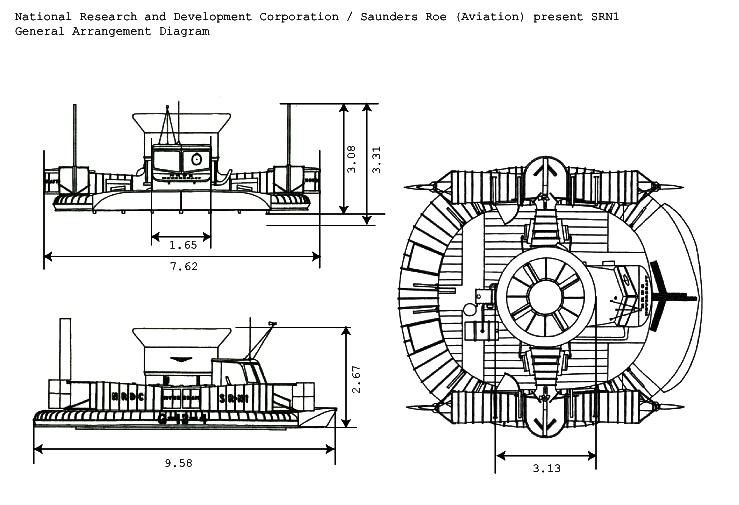

Saunders Roe, the flying boat firm at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, were given the contract, and the firm, under Cockerell’s guidance, worked avidly on the 20ft craft dubbed the ‘flying saucer’.

Ahead of schedule on 31st May 1959, the seven-ton craft flew, only eight months after the commencement of design work. But it was not until 11th June that she made her first public appearance in front of the world’s press. Such was the interest in this new form of transport that the press refused to leave until she was demonstrated in the water.

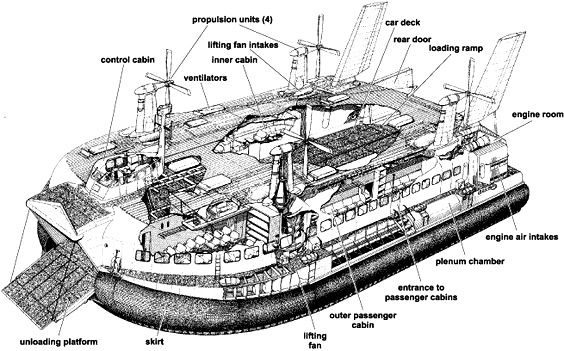

Within weeks, on 25th July she made a crossing of the English Channel, from Calais to Dover, with Cockerell aboard as human ballast, on the 50th anniversary of the first aeroplane crossing of the Channel. Cockerell’s dream had become a reality. Since then hovercraft carried over 80 million people and 12 million cars across the English Channel and were in continuous service for over 30 years before their retirement in October 2000.

Besides hovercraft he is attributed with the invention of wave power in the late 1970s, hovertrains and sidewall hovercraft (catamarans). Although Cockerell disagreed with the way the NRDC proceeded with hovercraft production, and in 1966 resigned from the board of Hovercraft Development, today hovercraft are enjoying a renaissance. Cheaper, quieter diesel engines, new construction materials and advanced skirt design mean that a hovercraft today is the same price as one 30 years ago. With developing countries having the greatest need for hovercraft, with shallows, coral reefs, mud flats, no ports and unprepared beaches, hovercraft are coming in to their own

On the last weekend in May 1999 the hovercraft industry launched Hovershow ’99 – the biggest show since 1966. Visitors were impressed by how the hovercraft has become a viable and versatile workboat and export sales in the year 1998-9 reached £20m. Recent sales have been to Canada for coastguards, to Lithuania as crew boats, to Hong Kong for fishery patrols, to Nigeria for oil crew boats, to Finland for coastguards to be used on ice and to Sri Lanka for military purposes. As Cockerell said, ‘Hovercraft will always be around – you can’t un-invent something!’

During the course of the weekend the 40th anniversary of the first flight of the hovercraft was celebrated, and Cockerell sent his best wishes but was too frail to attend. On the Monday a flypast was staged in his honour. He died the following day, with more patents to his name than he had years. The inventor of the hovercraft, died on the 40th anniversary of its launch at Hythe in Hampshire.

SAUNDERS ROE

The Saunders-Roe SR.N1 ("Saunders-Roe Nautical 1") was the first practical hovercraft. The concept has its origins in the work of British engineer and inventor Christopher Cockerell, who succeeded in convincing figures within the services and industry, including those within British manufacturer Saunders-Roe. Research was at one point supported by the

Ministry of

Defence; this was later provided by the National Research Development Corporation (NRDC), who had seen the potential posed by such a craft.

Testing had revealed several interesting tendencies of hovercraft, such as that there was an inevitable delay between the heading of the craft changing and the direction that it was travelling in would change to match. In addition, travelling overland posed more difficulty than traversing water due to the lack of motion attenuation generated by wave drag. Considerable skill on the part of the pilot was typically required to counter the effects of phenomenon such as cross winds and ground slopes.

MODEL TESTS - Saunders-Roe determined that, in addition to more theoretical work, a test programme involving a large-scale radio-controlled model would be necessary to provide sufficient data to make progress, and produced a proposal to this effect on 4 September 1958. In October 1958, the second stage of the contract was awarded, enabling advanced research into the development of the proposed air cushion and the corresponding principles, such as intake design, directional stability, and control; design studies were also performed for various sizes of hovercraft, ranging from 70-ton to 15,000-ton craft. It was at this point that the first pair of manned models were also proposed, of which Model A was selected to proceed with.

Airfix and Corgi models of the SR.N1

Né en Grande-Bretagne en 1910, Christopher Cockerell, l’homme qui allait donner des ailes aux bateaux en inventant l’aéroglisseur, manifesta très tôt ses dons d’innovateur. Par exemple le jour où il tenta de transformer la machine à coudre de sa mère en moteur à vapeur ! Ou lorsqu’il mit au point à l’école, un «bricolage» capable de recevoir la BBC. Ou, chez lui encore, quand son père dut revenir très vite sur la proposition qu’il lui avait faite pour le stimuler : 10 livres sterling par invention trouvée. Tout son patrimoine y serait passé ! Après avoir décroché son doctorat à Cambridge, il débute sa carrière chez Marconi.

L’armée

séduite la première

LINKS

INVENTORS A - Z

A CLEAN FUTURE - The Cross Channel Challenger (CCC) is a project currently on the drawing board looking for backing from 2020-21 over 75 weeks, to develop a coastal transport that is zero carbon. Vessels that are green could transform coastal tourism, making it socially acceptable in the face of a planet that will roast unless we do something about it.

This project has been costed to come in at around the £350k mark, hence the vessel does not include the latest lithium batteries or higher output solar cells, nor exotic materials in the build. It is a budget vessel to allow us to start the development ball rolling against a tide of nervous governmental departments looking for miracle solutions at bargain basement rates. The vessel is small for cross channel work, whereas as the length grows, so does the efficiency. Please bear this is mind; things can only get better.

The performance of this concept can be improved significantly by using the latest batteries and bigger wind turbines, allied to computer navigational software to define an efficient course.

|

|||

|

This website is copyright © 1991- 2019 Electrick Publications. All rights reserved. The bird logo and names Solar Navigator and Blueplanet Ecostar are trademarks ™. The Blueplanet vehicle configuration is registered ®. All other trademarks hereby acknowledged and please note that this project should not be confused with the Australian: 'World Solar Challenge'™which is a superb road vehicle endurance race from Darwin to Adelaide. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity working hard to promote world peace.

|