|

The Holy Grail is

commonly held to be a dish, plate, stone, or cup that is part of an important theme of Arthurian literature. A grail, wondrous but not explicitly "holy," first appears in Perceval le Gallois, an unfinished romance by Chrétien de Troyes: it is a processional salver used to serve at a feast. Chrétien's story attracted many continuators, translators and interpreters in the later 12th and early 13th centuries, including Wolfram von Eschenbach, who makes the grail a great precious stone that fell from the sky. The Grail legend became interwoven with legends of the Holy Chalice. The connection with Joseph of Arimathea and with vessels associated with the Last Supper and crucifixion of Jesus, dates from Robert de Boron's Joseph d'Arimathie (late 12th century) in which Joseph receives the Grail from an apparition of Jesus and sends it with his followers to Great Britain. Building upon this theme, later writers recounted how Joseph used the Grail to catch Christ's blood while interring him and how he founded a line of guardians to keep it safe in Britain. The legend may combine Christian lore with a Celtic myth of a cauldron endowed with special powers.

ORIGINS

The word graal, as it is earliest spelled, comes from Old French graal or greal, cognate with Old Provençal grazal and Old Catalan gresal, meaning "a cup or bowl of earth, wood, or metal" (or other various types of vessels in different Occitan

dialects). The most commonly accepted etymology derives it from Latin gradalis or gradale via an earlier form, cratalis, a derivative of crater or cratus which was, in turn, borrowed from Greek krater (a two-handed shallow cup). Alternate suggestions include a derivative of cratis, a name for a type of woven basket that came to refer to a dish, or a derivative of Latin gradus meaning "'by degree', 'by stages', applied to a dish brought to the table in different stages or services during a meal".

The Grail was considered a bowl or dish when first described by Chrétien de Troyes. Hélinand of Froidmont described a grail as a "wide and deep saucer" (scutella lata et aliquantulum profunda). Other authors had their own ideas: Robert de Boron portrayed it as the vessel of the Last Supper; and Peredur had no Grail per se, presenting the hero instead with a platter containing his kinsman's bloody, severed head. In Parzival, Wolfram von Eschenbach, citing the authority of a certain (probably fictional) Kyot the Provençal, claimed the Grail was a stone (called lapis exillis) that fell from Heaven, and had been the sanctuary of the neutral angels who took neither side during Lucifer's rebellion. The authors of the Vulgate Cycle used the Grail as a symbol of divine grace. Galahad, illegitimate son of Lancelot and Elaine, the world's greatest knight and the Grail Bearer at the castle of Corbenic, is destined to achieve the Grail, his spiritual purity making him a greater warrior than even his illustrious father. Galahad and the interpretation of the Grail involving him were picked up in the 15th century by Sir Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur, and remain popular today.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, after the cycle of Grail romances was well established, late medieval writers came up with a false etymology for sangréal, an alternative name for "Holy Grail." In Old French, san graal or san gréal means "Holy Grail" and sang réal means "royal blood"; later writers played on this pun. Since then, "Sang real" is sometimes employed to lend a medievalising air in referring to the Holy Grail. This connection with royal blood bore fruit in a modern bestseller linking many historical conspiracy theories.

LEGEND

Belief in the Grail and interest in its potential whereabouts has never ceased. Ownership has been attributed to various groups (including the Knights Templar, probably because they were at the peak of their influence around the time that Grail stories started circulating in the 12th and 13th centuries).

There are cups claimed to be the Grail in several churches, for instance the Saint Mary of Valencia Cathedral, which contains an artifact, the Holy Chalice, supposedly taken by Saint Peter to Rome in the 1st century, and then to Huesca in Spain by Saint Lawrence in the 3rd century. According to legend, the monastery of San Juan de la Peña, located at the south-west of Jaca, in the province of Huesca, Spain, protected the chalice of the Last Supper from the Islamic invaders of the Iberian Peninsula. Archaeologists say the artifact is a 1st century Middle Eastern stone vessel, possibly from Antioch, Syria (now Turkey); its history can be traced to the 11th century, and it now rests atop an ornate stem and base, made in the Medieval era of alabaster, gold, and gemstones. It was the official papal chalice for many popes, and has been used by many others, most recently by Pope Benedict XVI, on July 9, 2006. The emerald chalice at Genoa, which was obtained during the Crusades at Caesarea Maritima at great cost, has been less championed as the Holy Grail since an accident on the road, while it was being returned from Paris after the fall of Napoleon, revealed that the emerald was green glass.

In Wolfram von Eschenbach's telling, the Grail was kept safe at the castle of Munsalvaesche (mons salvationis), entrusted to Titurel, the first Grail King. Some, not least the Benedictine monks of Montserrat, have identified the castle with the real sanctuary of Montserrat in Catalonia, Spain. Other stories claim that the Grail is buried beneath Rosslyn Chapel or lies deep in the spring at Glastonbury Tor. Still other stories claim that a secret line of hereditary protectors keep the Grail, or that it was hidden by the Templars in Oak Island, Nova Scotia's famous "Money Pit", while local folklore in Accokeek, Maryland says that it was brought to the town by a closeted priest aboard Captain John Smith's ship.

MODERN INTERPRETATIONS

The story of the Grail and of the quest to find it became increasingly popular in the 19th century, referred to in literature such as Alfred Tennyson's Arthurian cycle the Idylls of the King. The combination of hushed reverence, chromatic harmonies and sexualized imagery in Richard Wagner's late opera Parsifal gave new significance to the grail theme, for the first time associating the grail – now periodically producing blood – directly with female fertility. The high seriousness of the subject was also epitomized in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's painting (illustrated), in which a woman modelled by Jane Morris holds the Grail with one hand, while adopting a gesture of blessing with the other. A major mural series depicting the Quest for the Holy Grail was done by the artist Edwin Austin Abbey during the first decade of the 20th century for the Boston Public Library. Other artists, including George Frederic Watts and William Dyce also portrayed grail subjects.

The Grail later appeared in movies; it debuted in a silent Parsifal. In The Light of Faith (1922), Lon Chaney attempted to steal it. The Silver Chalice, a novel about the Grail by Thomas B. Costain was made into a 1954 movie. Lancelot du Lac (1974) was made by Robert Bresson. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) (adapted in 2004 as the stage production Spamalot) was a comedic adaptation. John Boorman, in his film Excalibur, attempted to restore a more traditional heroic representation of an Arthurian tale, in which the Grail is revealed as a mystical means to revitalise Arthur and the barren land to which his depressive sickness is connected. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and The Fisher King are more recent adoptions.

The Grail has been used as a theme in fantasy, historical fiction and science fiction; a quest for the Grail appears in Bernard Cornwell's series of books The Grail Quest, set during The Hundred Years War. Michael Moorcock's fantasy novel The War Hound and the World's Pain depicts a supernatural Grail quest set in the era of the Thirty Years' War, and science fiction has taken the Quest into interstellar space, figuratively in Samuel R. Delany's 1968 novel Nova, and literally on the television shows Babylon 5 and Stargate SG-1 (as the "Sangraal"). Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon has the grail as one of four objects symbolizing the four Elements: the Grail itself (water), the sword Excalibur (fire), a dish (earth), and a spear or wand (air). The Grail features heavily in the novels of Peter David's Knight trilogy, which depict King Arthur reappearing in modern-day New York City, in particular the second and third novels, One Knight Only and Fall of Knight. The grail is central in many modern Arthurian works, including Charles Williams's novel War in Heaven and his two collections of poems about Taliessin, Taliessin Through Logres and Region of the Summer Stars, and in feminist author Rosalind Miles' Child of the Holy Grail. The Grail also features heavily in Umberto Eco's 2000 novel Baudolino.

The Grail has also been treated in works of non-fiction, which generally seek to interpret its meaning in novel ways. Such a tack was taken by psychologists Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz, who used analytical psychology to interpret the Grail as a series of symbols in their book The Grail Legend. This type of interpretation had previously been used, in less detail, by Carl Jung, and was later invoked by Joseph Campbell.

Other works attempt to connect the Grail to conspiracy theories and esoteric traditions. In The Sign and the Seal, Graham Hancock asserts that the Grail story is a coded description of the stone tablets stored in the Ark of the Covenant. For the authors of Holy Blood, Holy Grail, who assert that their research ultimately reveals that Jesus may not have died on the cross, but lived to wed Mary Magdalene and father children whose Merovingian lineage continues today, the Grail is a mere sideshow: they say it is a reference to

Mary Magdalene as the receptacle of Jesus' bloodline.

Such works have been the inspiration for a number of popular modern fiction novels. The best known is Dan Brown's bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code, which, like Holy Blood, Holy Grail, is based on the idea that the real Grail is not a cup but the womb and later the earthly remains of Mary Magdalene (again cast as Jesus' wife), plus a set of ancient documents claimed to tell the true story of Jesus, his teachings and descendants. In Brown's novel, it is hinted that Jesus was merely a mortal man with strong ideals, and that the Grail was long buried beneath Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland, but that in recent decades its guardians had it relocated to a secret chamber embedded in the floor beneath the Inverted Pyramid near the Louvre Museum. The latter location, like Rosslyn Chapel, has never been mentioned in traditional Grail lore.

They

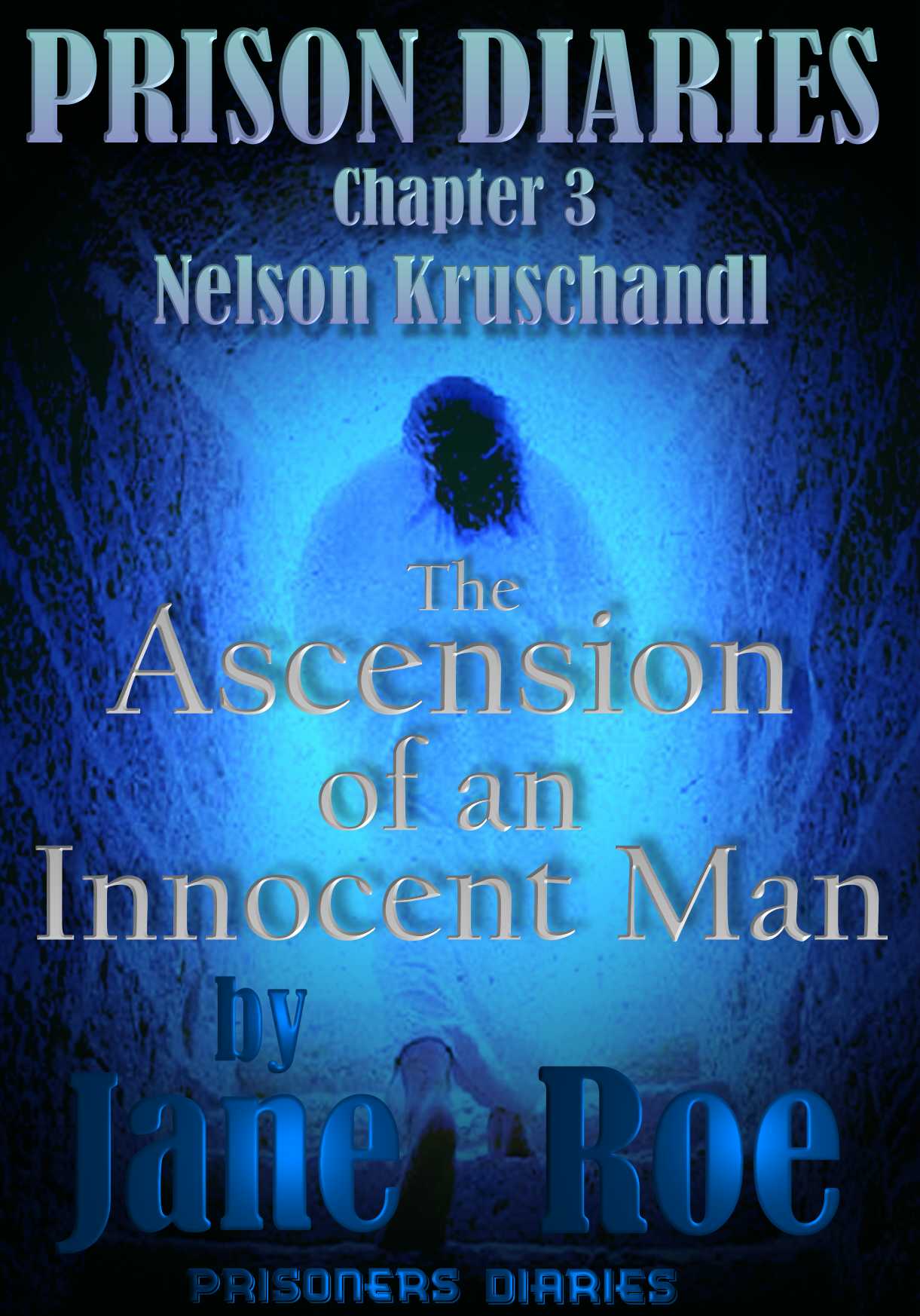

crucified him. The local police produced evidence at his trial that was guaranteed

to convict him, then made sure the local

press

published details of his conviction

so that nobody would believe

his revelations about corruption in local government. The so-called forensic

evidence turned out to be junk science, a natural feature that was

understood in the USA to be just that - had not found its way into UK

guidance. Presented in court as controversial, what the Crown's expert meant

was that US studies did not accord with UK studies at the time. Two months

after the trial the UK studies recognised the US studies. The victim of this

injustice would not learn that until three years into his sentence. The CCRC

did not tell him about the cases they had referred to the Court of Appeal -

and in his case, they turned a blind eye. This is a true story based on

official documents. Not to be published until after the subject's appeals in

Europe are heard.

His barrister didn't show the jury the accused' diaries, he should have, because the girl's mother reminded the accused to send Valentines cards every year - which she, err, seems to have forgotten to mention to the court.

She also forgot to tell the prosecution about the existence of her own diaries. These diaries reveal that the accused was not alone with the girl as she had claimed. Why do you suppose her mother might hide this information?

The accused was instructed not to venture why the girl should make up her story by his barrister, but of course he has a good idea. Sadly, that cannot be revealed just yet for legal reasons. He did say he could forgive a 15 year old for some kind of unthinking hormone driven revenge for not doing what she had wanted, but not a mature woman - who would have known better. The accused had refused to get together with the girls mother. The girl wanted the accused to get together with her mother. It's an or-else situation and the accused was threatened - which information the defence lawyers failed to introduce - despite instructions to the contrary.

Local newspapers breached a Court Order prohibiting publication, and published mid-trial, which to us seem the most damaging time to publish, to virtually guarantee conviction. Nearly all the local papers published at the same time - in orchestrated fashion - obviously from a shared source; presumably the reporter attending. Is that responsible reporting?

Once they had convicted the victim of this injustice, the Crown tried to prevent him publishing his story. Why would they do that? Fortunately, Judge Cedric Joseph (this was his last case) was persuaded by barrister Michael Harrison, that that would breach the chaps human rights. The Judge agreed, subject to not naming the girl or her mother.

We think that the Crown's reluctance is to do with the way they obtained their conviction. It was based on medical testimony, which itself was based on out of date guidance from the Royal College of Paediatric and Child Health from 1997. New guidance was issued in 2008, just one month after the trial. Why did the Crown not wait the extra month before going to trial? Well, we know the answer to that, the new guidance confirmed that certain internal marks are naturally occurring. The prosecution told the jury (or, rather, allowed their pet witness to say it for them - which amounts to the same thing) that they were supportive of the allegations - which was a deception on the part of the Crown.

The Crown had kept the defence waiting for more than 18 months and delayed matters by refusing to hand back vital computer information that they'd confiscated - claiming they might find pornographic images. Of course the Crown were just making this up and instead of letting the jury know that

all of the accused' computers were image free, they refused to confirm the results of their investigations!

Normally, a report on confiscated machines is supplied to the defence. Don't you think the jury should have known that this

man's computers were clean?

You'll have to wait for the subject's appeals in the ECHR to conclude before this book is published. Maybe then we'll see an official version in 2016/2017? European appeals take 4 years on average, from the date of lodge. But first you have to exhaust any domestic remedy. He has finally, as of February 2013.

This man served nearly four years for a crime he did not commit. If you would like to know more about this developing story, please Contact Us.

LINKS

and REFERENCE

GNU

free documentation license

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resurrection_of_Jesus

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Grail

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus_Christ

Wikipedia

Holy_Grail

Wikipedia

Resurrection_of_Jesus

Wikipedia

Jesus_Christ

|