|

Digital

proportional radio control equipment is the life blood of modeling, without

which what would we use to control our model cars, boats and aircraft. Radio control (often abbreviated to R/C or simply RC) is the use of radio signals to remotely control a device. Radio control is used for control of model vehicles from a hand-held radio transmitter. Industrial, military, and scientific research organizations make use of radio-controlled vehicles

and commercial sets as well.

RADIO CONTROLLED HISTORY

The first general use of radio control systems in models started in the early 1950s with single-channel self-built equipment; commercial equipment came later. The advent of transistors greatly reduced the battery requirements, since the current requirements at low voltage were greatly reduced and the high voltage battery was eliminated. In both tube and early transistor sets the model's control surfaces were usually operated by an electromagnetic escapement controlling the stored energy in a

rubber-band loop, allowing simple on/off rudder control (right, left, and neutral) and sometimes other functions such as motor speed.

Crystal-controlled superheterodyne receivers with better selectivity and stability made control equipment more capable and at lower cost. Multi-channel developments were of particular use to aircraft, which really needed a minimum of three control dimensions (yaw, pitch and motor speed), as opposed to boats, which required only two or one.

As the electronics revolution took off, single-signal channel circuit design became redundant, and instead radios provided proportionally coded signal streams which a servomechanism could interpret, using pulse-position modulation (PPM).

More recently, high-end hobby systems using Pulse-code modulation (PCM) features have come on the market that provide a computerized digital bit-stream signal to the receiving device, instead of the earlier PPM encoding type. However, even with this coding, loss of transmission during flight has become more common, in part because of the ever more wireless society. Some more modern FM-signal receivers that still use "PPM" encoding instead can, thanks to the use of more advanced computer chips in them, be made to lock onto and use the individual signal characteristics of a particular PPM-type RC transmitter's emissions alone, without needing a special "code" transmitted along with the control information as PCM encoding has always required.

In the early 21st century, 2.4 gigahertz spread spectrum RC control systems have become increasingly utilized in control of model vehicles and aircraft. Now, these 2.4 GHz systems are being made by most radio manufacturers. These radio systems range from a couple thousand

dollars, all the way down to under US$30 for some. Some manufacturers even offer conversion kits for older digital 72 MHz receivers and radios. As the emerging multitude of 2.4 GHz band spread spectrum RC systems usually use a "frequency-agile" mode of operations, like FHSS that do not stay on one set frequency any longer while in use, the older "exclusive use" provisions at model flying sites needed for VHF-band RC control

system's frequency control, for VHF-band RC systems that only used one set frequency unless serviced to change it, are not as mandatory as before.

THE

ESSENTIALS RC electronics have three essential elements. The transmitter is the controller. Transmitters have control sticks, triggers, switches, and dials at the user's finger tips. The receiver is mounted in the model. It receives and processes the signal from the transmitter, translating it into signals that are sent to the servos. The number of servos in a model determines the number of channels the radio must provide.

Typically the transmitter multiplexes all the channels into a single pulse-position modulation radio signal. The receiver demodulates and

de-multiplexes the signal and translates it to the special kind of pulse-width modulation used by standard RC servos.

In recent years, electronic speed controllers (ESCs) have been developed to replace the old variable resistors, which were extremely inefficient. They are entirely electronic, so they do not require any moving parts or servos.

In the 1980s, a Japanese electronics company, Futaba, copied wheeled steering for RC cars. It was originally developed by Orbit for a transmitter specially designed for Associated cars. It has been widely accepted along with a trigger control for throttle. Often configured for right hand users, the transmitter looks like a pistol with a wheel attached on its right side. Pulling the trigger would accelerate the car forward, while pushing it would either stop the car or cause it to go into reverse. Some models are available in left-handed versions.

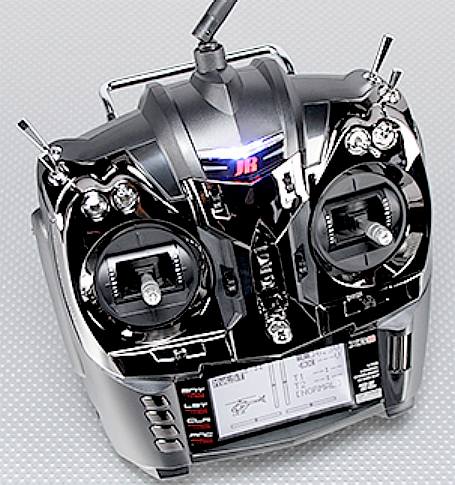

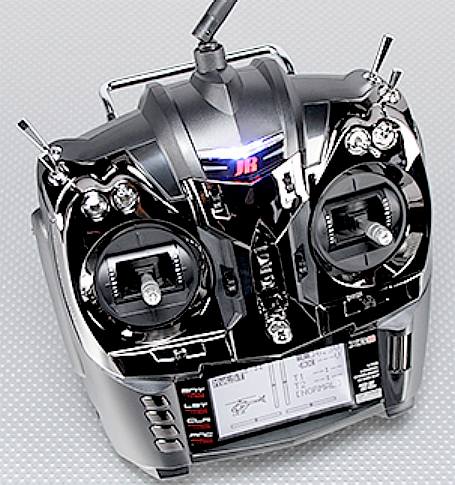

RIGHT:

Etronix have released an updated version of their highly popular Pulse RC radio systems.

These 2.4ghz radio systems use the latest Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) technology that eliminates signal interference from other users making them the ideal choice for car, boat and aircraft model enthusiasts.

With very attractive pricing they are extremely popular with modellers running on a budget.

|

Features:

Mode 2 (Throttle on left hand stick)

2.4ghz (No Crystals)

6-Channel

Servo Reversing

Throttle Position Neutral Failsafe

Delta Wing Mode Mixing

Charging Jack

|

Specification:

Frequency: 2.4ghz ISM Frequency Range

Modulation: GFSK

Spread Spectrum Mode: FHSS

Number of Frequency Channels: 20

Output Power: <=20dbm

Working Current: <=150mA

Working Voltage: 1.2v x 4 (AA/Nimh) |

MASS

PRODUCTION

There are thousands of RC vehicles available. Most are toys suitable for children. What separates toy grade RC from hobby grade RC is the modular characteristic of the standard RC equipment. RC toys generally have simplified circuits, often with the receiver and servos incorporated into one circuit. It's almost impossible to take that particular toy circuit and transplant it into other RCs.

Hobby grade radio

control systems have modular designs. Many cars, boats, and

aircraft can accept equipment from different manufacturers, so it is possible to take RC equipment from a car and install it into a boat, for example.

However, moving the receiver component between aircraft and surface vehicles is illegal in most countries as radio frequency laws allocate separate bands for air and surface models. This is done for safety reasons.

Most manufacturers now offer "frequency modules" (known as crystals) that simply plug into the back of their transmitters, allowing one to change frequencies, and even bands, at will. Some of these modules are capable of "synthesizing" many different channels within their assigned band.

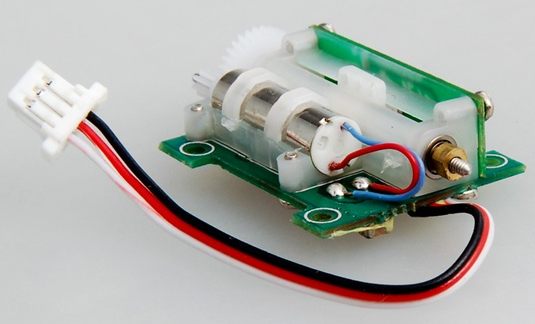

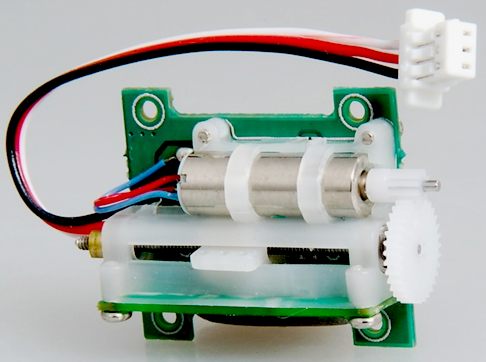

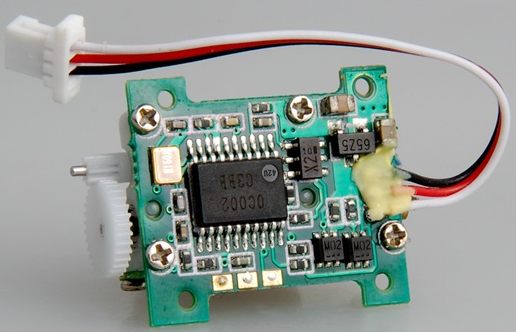

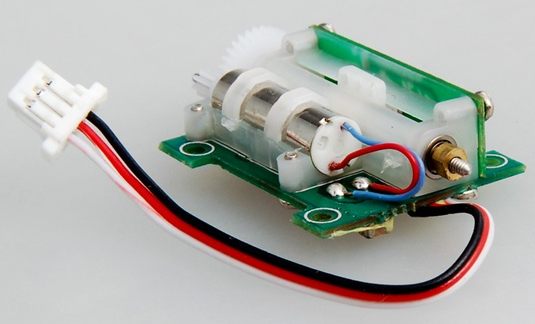

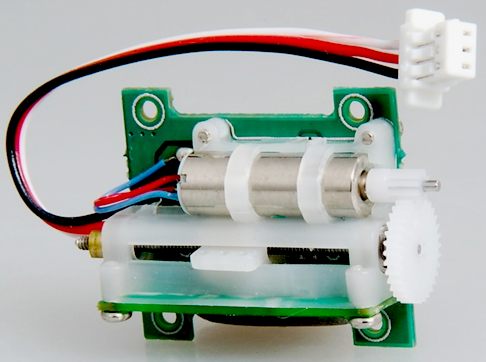

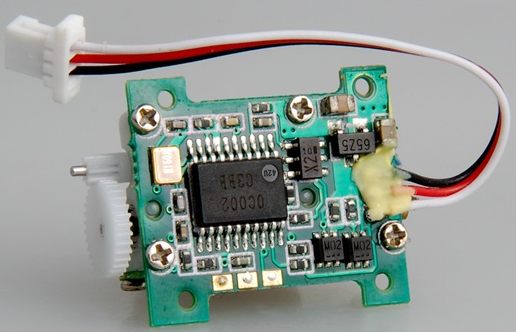

Linear

helicopter servo, showing the microchip controller and ball bearings in which

the screw threaded shaft runs.

HOBBY MODELS

Hobby grade models can be fine tuned, unlike most toy grade models. For example, cars often allow toe-in, camber and caster angle adjustments, just like their real-life counterparts. All modern

"computer" radios allow each function to be adjusted over several parameters for ease in setup and adjustment of the model. Many of these transmitters are capable of "mixing" several functions at once, which is required for some models.

Many of the most popular hobby grade radios were first developed, and mass-produced in Southern California by Orbit, Bonner, Kraft, Babcock, Deans, Larson, RS, S&O, and Milcott. Later,

Japanese companies like

Futaba, Sanwa and

JR (Macgregor)

took over the market. LEGACY

FOCUS & RANGER SETS

The

Focus and Ranger radio control sets used by the SolarNavigator team from

1998 until 2005,

were supplied by Amerang at Lancing in Sussex - and they are still going

strong.

LEFT:

Futaba

radio control sets - unmodified - a superb package at the time that when

combined gave 7 true digital proportional channels. RIGHT: Customised version

for controlling up to seven proportional functions with only one pair of hands.

The cases were cut to give a flat mating surface and then welded together again.

Then the aerials were mounted to the left with the power meters on the right. We

have seen two sets clipped to a board before and thought about that, but this

way everything is so much more compact.

The

Hitec speed controller below is no longer in production, however, the pair we have been using

since 1996 has seen service in four of our development models and may

yet see us through to the end. As with our radio sets, these were supplied by

Amerang

Limited, Lancing in Sussex (see contact details below).

In July 2013, Ripmax bought

the wholesale toy distributor Amerang from the Modelzone Group, which was under administration, saving the jobs of all 18 remaining employees of Amerang.

Hitec

Sp-6/10A controller and a lithium battery pack

|

The

SP-610 speed control is good for slow, scale boat, low power

applications using motors up to the 550 class. It is a full MOSFET,

two-way speed control and comes in a sturdy aluminum case. It is

ideal for a solar powered model boat, because solar boats operate

quite well with lower power.

|

|

FEATURES:

|

|

*Fused

for Polarity Protection

*Integral

Case Heat Sink

|

|

SPECIFICATIONS:

|

|

Operating

Voltage

|

6.0

- 8.4 Volts / 5-7 Cells

|

|

Continuous

Amperage

|

6

- 10 Amps

|

|

|

English

|

|

|

Size

L x W x H

|

|

|

|

Weight

|

|

|

Amerang Limited

Unit 2 The Quadrant

60 Marlborough Road

Lancing Business Park

Lancing, West Sussex,

BN15 8UW, United Kingdom

Telephone: +44 (0) 1903 765496 / 752866

http://www.amerang.co.uk/

Ripmax Ltd.

241 Green Street,

Enfield, EN3 7SJ

England, United Kingdom

Telephone: +44(0)20 8282 7500

Fax: +44(0)20 8282 7501

Contact Email: mail@ripmax.com

Futaba Services Email: service@ripmax.com

http://www.ripmax.com

Telephone: +44 (0) 1903 765496 / 752866 or 07000 AMERANG

Fax: +44 (0) 1903 765178 / 753643

OUR

ELECTRONICS DESIGNER CONTROL

ELECTRONICS SOLAR

WINGS

The

SolarNavigator

is a robotic

electric trimaran with an extremely efficient hull.

You

can follow the build and testing of this revolutionary 2m model boat with the

modified Futaba Focus and Focua Ranger radio control sets by clicking on the

picture above.

The

design of the Solar Navigator boat

has been licensed for use in

the

John Storm series of books by

Jameson Hunter

|