|

G20

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

OUR CHILDREN - We owe it to future generations to do what we can to try and reverse the damage we have inflicted on our oceans with our careless attitude to dumping waste. World leaders should assume the mantle of responsibility on a no-fault basis and work together to for the common cause. We should aim to leave the planet in a better state than our generation inherited it.

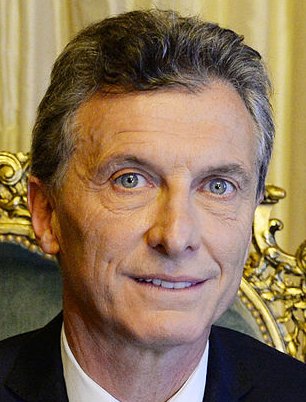

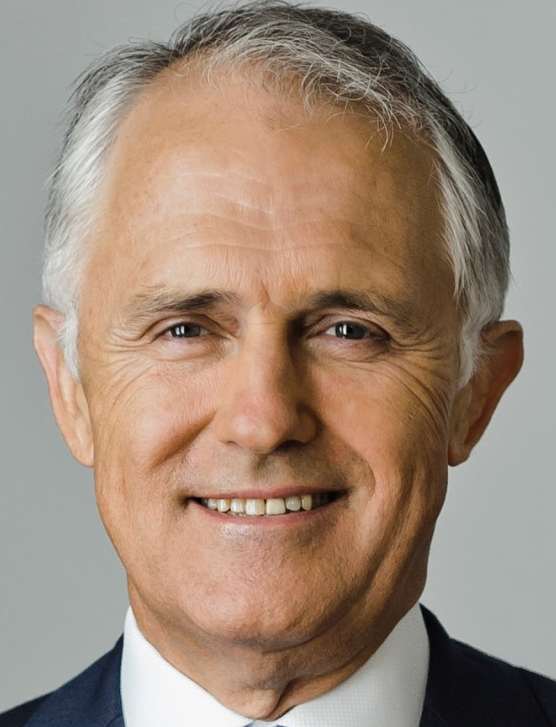

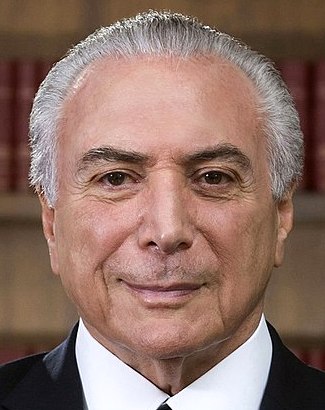

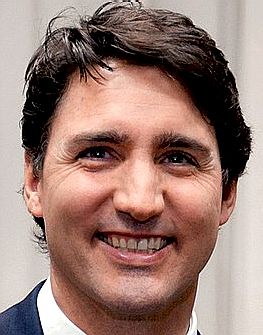

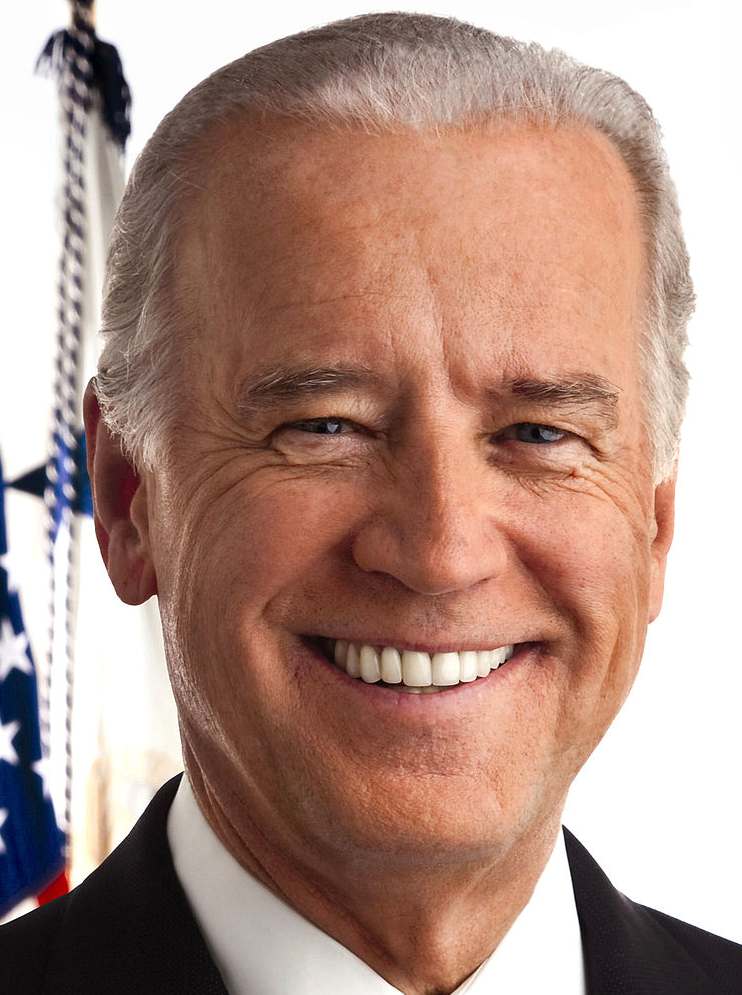

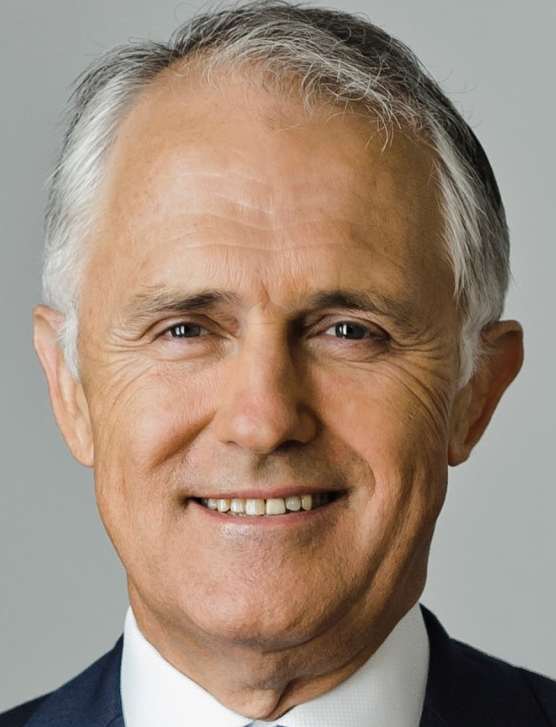

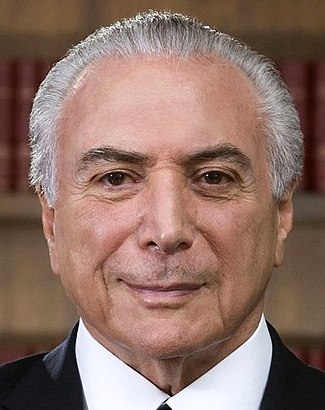

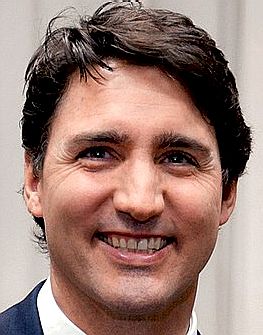

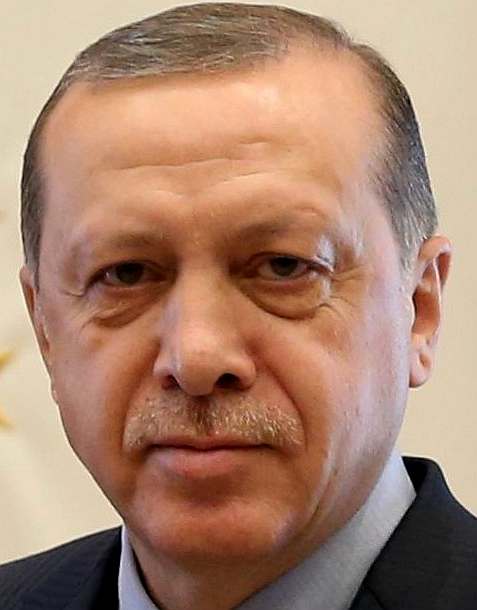

THE G20 HEADS OF STATE (2020) A - Z

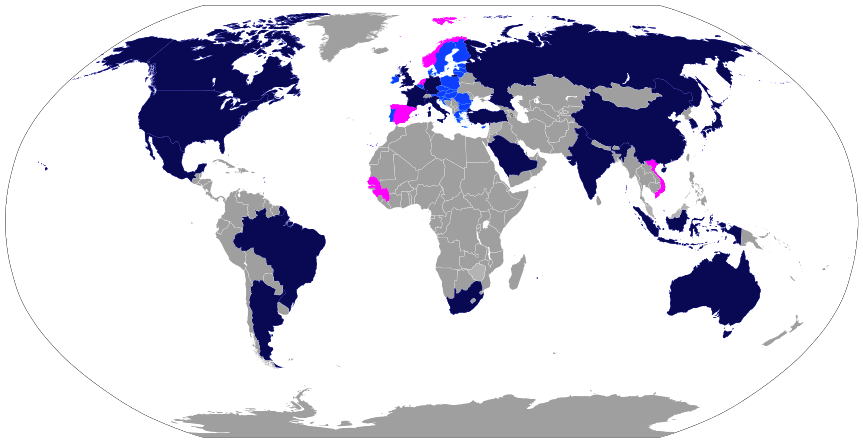

The G20 (or G-20 or Group of Twenty) is an international forum for governments and central bank governors that is more inclusive and representational of world output, from:

Argentina - Australia - Brazil - Canada - China European Union - France - Germany - India - Indonesia Italy - Japan - Mexico - Russia - Saudi Arabia South Africa - South Korea - Turkey - United Kingdom - United States

Founded in 1999, the G20 aims to discuss policy pertaining to the promotion of international financial stability. It seeks to address issues that go beyond the responsibilities of any one organization such as ocean devastation.

FOOD SECURITY

The following table is suggestive of an appropriate contribution towards ocean cleaning research and anti-plastic cooperation (or a plastic understanding) between the heads of state and economic advisers in connection with ensuring the future of the blue economy, with an especial slant toward future food security. This will pay for an Ocean Action Plan called SeaNet.

SEANET - OCEAN ACTION PLAN (FOOD SECURITY EXAMPLE)

The World needs an Ocean Action Plan to coordinate the efforts of member nations that in turn will benefit each other as the oceans transport waste from one shoreline to the shores of a neighbor country.

To help develop an international strategy responsible heads of state need to generate sufficient funds for an organization to allow them to effectively make headway. This is estimated to be in the region of $10 million dollars to develop a SeaVax prototype as an example of what is possible and by way of freeware to and for potential operators in any contributing country.

Follow on expenses, or pledges of ongoing support should be included to cover the cost of helping contributing nations to set up fleets of ocean cleaning boats - and running them in a network or pattern such as SeaNet, to stand a better chance of regenerating our oceans.

TIMESCALE

If world leaders can agree to contribute within 12 months from July 2018, it would take around three years from that Agreement to get things moving and produce a SeaVax prototype - assuming cooperation from all members of such an Alliance.

From a point in time where a SeaVax (type) prototype was deemed sufficiently proven to go into production, it would take five AmphiMax portable boatyards to produce 8 SeaVax units a year each (@ six week assembly time) that could launch 40 SeaVax ships collectively. If this formula were used as a guide, it would take 3 years to complete a proposed fleet of 120 SeaVax (type) vessels for the Indian Ocean, without clogging up that nation’s shipyards.

A similar plan would proceed in tandem for the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, meaning that within 3 years a global fleet of 360 ocean dustcarts could be operational.

It would then take an estimated five years to make an impact on fish stocks - as in stabilization - and within 10 years we might reasonably anticipate a percentage recovery of roughly 0.5% a year, meaning that it would take 96 years for our ocean fish stocks to recover to 1970 levels, by 2114. This assumes parallel action to tackle climate change and international bans on single use plastic, or better recycling rates on land.

ONE WORLD ONE OCEAN - In the role of guardians of your geographical regions, there is also a responsibility to develop the blue economy for the international circular economies that a sustainable society requires if we are not to burn planet earth out.

REDUCING OCEAN RECOVERY TIME (EXAMPLE)

The only way to improve on the 2114 figure would be to operate more SeaVax vessels:

SeaVax x 720 = 48 years

SeaVax x 1440 = 24 years

This is on the assumption that filtration time does not reach total waste absorption, which is likely at some point even at 360 SeaVax vessels.

ECONOMICS

The blue economy is said to be valued at $24 trillion in total* (USD). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the world production of fish in 2005 consisted of 93.2 million tonnes captured by commercial fishing in wild fisheries. The number of individual fish caught in the wild has been estimated at up to 2.7 trillion per year.

Of this the net value = 93.2m x 6668* ($/ave/tonne) = $621,457,600,000

Divide this up by the area of our oceans (344.8m km2): $ 1,802,371,230 per million square kilometers. Hence:

It is as yet not possible to suggest a rate of ocean recovery with any accuracy, as insufficient data exists. But, if we were to aim for just 1/10th of one percent for ocean recovery per annum, this would give us a return of $621,457,600 million ($.6.2m) in dollar value in terms of fish recovery per year.

In ten years that equates to: $6,214,576,000 ($6.2b) and so on.

On top of that we add the value of the recovered plastic, and on top of that the fact that toxin levels should drop dramatically in terms of bio-accumulation, making fish safe to eat once more.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 2018

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

WORLD LEADERS - Sometimes find it hard to agree on ways forward. This may be because they are not experts in the subject, or cannot see the economic benefits of technology. They do though fund academic research and typically agree on the value of learning institutions. If there is an economic value to cooperation, they might commission, fund, or otherwise support an organization that is working for them to achieve a common goal - or report back if it transpires that a result may not be possible. Either way world leaders benefit from the knowledge gained, provided the exercise is affordable.

Red tape is the enemy of advance where academics are too busy becoming experts at making applications for grant funding that might otherwise be spent in the field. Any application process that is overly complicated tends to dissuade entrepreneurs from investing their time and energy that might otherwise be spent on real progress in other endeavours, such as starting a regular business, that will yield an income while achieving nothing innovative at all.

Sustainable Ocean Economy, Innovation and Growth: A G20 Initiative for the 7th Largest Economy in the World

Kristian Teleki (Prince of Wales’ Charities International Sustainability Unit (ISU)) Mia Pantzar (Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP)) Michael K. Orbach (Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions) Daniela Russi (Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP)) John Virdin (Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions) Anna-Kathrina Hornidge (Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT)) Andrew Farmer (Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP)) Martin Visbeck (GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel) Patrick ten Brink (Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP)) Benjamin Boteler (Ecologic Institute) R. Andreas Kraemer (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)) Miguel Herédia (Fundação Ocean Azul – Oceano Azul Foundation) Ina Krüger (Ecologic Institute) Grit Martinez (Ecologic Institute) Linwood Pendleton (Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions) Tiago Pitta e Cunha (Fundação Ocean Azul – Oceano Azul Foundation) Julien Rochette (Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI)) Cyrus Rustomjee (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)) Torsten Thiele (Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS Potsdam)) Scott Vaughan (International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD))

G20

should initiate a global Ocean governance process and call for Ocean

Economy dialogues, strategies and regional cooperation to ensure

that investment and growth in ocean use become sustainable and reach

their full potential. The ocean is the largest and a most critical ecosystem on Earth, with many interactions between the ocean Sustainable Development Goal (SDG14) and other SDGs. It is one of the most biologically diverse and highly productive system on the planet, and potentially the largest provider of food, materials, energy, and ecosystem services. However, past and current maritime sectors’ uses of the ocean continue to be unsustainable. Increasing demand for resources, technological advances, overfishing, climate change, pollution, biodiversity and habitat loss, along with inadequate stewardship and law enforcement, are contributing to the ocean’s decline.

As a standing agenda item for the G20, and with associated good governance, a sustainable Ocean Economy can improve the health and productivity of ocean ecosystems, and reverse the current cycle of decline. Better governance, appreciation of the economic value of the ocean and ‘Blue Economy’ strategies can reduce conflicts among uses, ensure financial sustainability, ecosystem integrity and prosperity, and promote long-term national growth and employment in maritime industries.

CHALLENGE

Germany’s G20 Presidency could have helped to strengthen the growing ocean economy by calling for national Ocean or Blue Economy Development Frameworks, coordination among coastal and ocean states, and for integrated and ecosystem-based management ensuring the ocean economy is sustainable.

The G20 countries have a special responsibility towards the ocean. They are all coastal states with 45% of the world’s coastline among them, and jurisdictional responsibility over 21% of exclusive economic zones (Shugart-Schmidt et alii 2015). Argentina and India are committed to addressing the ocean economy in their upcoming G20 Presidencies. Complementing the G20, Italy’s current G7 Presidency has a broad ocean agenda, with a focus on cooperation in regional seas, building on the Presidencies of Germany (2015) and Japan (2016). Canada may consider the ocean in its G7 Presidency in 2018.

The ocean covers 71% of the Earth’s surface and provides both renewable and non-renewable resources that sustain hundreds of millions of livelihoods in coastal areas and on islands, and in inland areas. 80% of life on Earth is in the ocean, 50% of the available oxygen is from the ocean, which is also the largest carbon sink, absorbing about a quarter of the carbon dioxide emitted, thus reducing global warming. It also absorbs 90% of the additional heat caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

The ocean’s productivity is greatly reduced and likely to deteriorate further because of overfishing and destruction of ecosystems by bottom trawling, sea-bed mining and offshore industries (e.g. oil and gas extraction), pollution from maritime industries and land-based activities, urban development of coasts, acidification caused by CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, and warming of the ocean. The rapid acidification destroys critical ecosystems, such as coral reefs, and the ocean’s ability to provide the fish and seafood as a source of protein in 20 to 30 years. Current trends cannot be allowed to persist, or there will be 1kg of plastic waste in the ocean for every 3 kg of fish by 2025. More plasticin the ocean with many of the chemicals they contain poses a great risk of contaminating the food system. Marine litter, which is mostly plastic was an issue in the G7 presidencies of Germany (2015) and Japan (2016).

The ocean is a great potential driver of economic growth, jobs, and innovation, and expected to provide economic opportunities in the future. The (lower bound) of the value of key ocean assets has been estimated at US$24 trillion and the value of derived services at US$2.5 trillion per year (Hoegh-Guldberg et alii 2015: Lillebø et alii 2017) or US$1.5 trillion without non-market benefits (OECD 2016). This is equivalent to 3-5% of global GDP or possibly the size of France or California.

The value of ocean is reduced by environmental pressures from overfishing, climate change, pollution, loss of habitats and biological diversity, and urban development of coasts, which are symptoms of weak ocean governance (GOC 2014, 2016). Despite progresss with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), there are gaps and outdated approaches in ocean-related policy and law, and severe shortcomings in implementation and law enforcement, resulting in many unregulated, partly Illegal activities, and inadequate or non-existent stewardship of many parts of the ocean. Bad governance increases investment risks and holds back growth of a sustainable ocean economy.

The challenge is now understood, but meaningful action is still pending. SDG14 is a universally agreed instruction to conserve the ocean, seas and marine resources, and use it sustainably – with a focus on the access and benefits for small island states and small-scale fishers. The UN Ocean Conference in June 2017 will highlight the ocean’s importance for sustainable development and the relationship of a healthy ocean to all other SDGs. The UN climate negotiations are also considering the ocean’s role in the climate system, and the effects of global warming, ocean acidification, increased energy in the ocean, and accelerating sea-level rise on island and coastal communities, and their adaptation needs.

Germany’s G20 Presidency initiative on the ocean economy is sure to have support and follow-up.

PROPOSAL

The Ocean or Blue Economy – the human use of the ocean – is rapidly expanding. We are at the threshold of a new wave of industrialisation and exploitation of the ocean (McCauley at alii 2015). It holds the promise of more innovation, growth and jobs (UNEP et alii 2012; UNEP 2015; OECD 2016; Patil et alii 2016; Rustomjee 2016a+b; Bhatia 2017a+b). As the Ocean Economy expands, the world must ensure that maritime industries and the use of ocean space, resources and ecosystems are ecologically sustainable; economic activities must be in balance with the long-term carrying capacity of the ocean ecosystems (Visbeck et alii 2014, Silver et alii 2015). They also need to be sensitive to regional differences and conditions (e.g. Kildow 2016; Bhatia 2017a+b) and demands on resources.

In parallel, it is important to acknowledge that different measures to support conservation of ocean ecosystems and biological resources, for example the designation of marine protected areas (MPAs), can generate economic benefits both to individual sectors and to society overall through the delivery of wider ecosystem services and increased human wellbeing. The realisation of such synergies, however, depends on various factors, including that the MPAs and their regulatory measures are designed and managed in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, that sufficient resources are allocated for effective monitoring and enforcement, and that any benefits accrued are shared fairly (Russi et al 2016). Valuable as well-managed MPAs with effective enforcement may be, they are no substitute for effective governance of the whole ocean.

Our understanding of the links between economic development and maintained environmental sustainability in the marine environment is still developing, but action cannot wait. The state of the ocean is anything but satisfactory (UN 2016). Let our past experiences with whaling, fishing of species to (commercial) extinction, and the aggregate effects of marine pollution be warnings (G7 Science Academies 2015; Spalding 2016; Arnason et alii 2017). The current state of the ocean and projected future exploitation and use calls for G20 leadership to ensure the new Ocean Economy is “green”, that the integrity and productivity of ocean ecosystems is maintained, and, where possible, restored (Visbeck et alii 2014, Golden et alii 2017).

The responsibility of the G20 countries in the global community goes beyond their shares of coastlines and marine areas. The world is looking to them to provide robust coastal and ocean governance and leadership in the protection of the ocean, maintaining the integrity of its ecosystems, and the sustainable use of ocean resources. The ocean is clearly an important part of the world economy, and a potential driver of sustainable growth in the future. However, this growth is only possible with better and more complete ocean governance and blue economy strategies that break the past trends.

The consequences for the ocean of unsustainable patterns of (largely terrestrial) industrialisation, production and consumption are illustrated in Figure 1. It shows how the rise of gross world product (global GDP) is coupled with plastic waste dumped and washed into the ocean, the rise in dead zones in the ocean (where there is no oxygen to sustain the ecosystem), and with overfishing. There are just a few of the many interlocking challenges that need to be addressed to ensure ocean health, the integrity and productivity of ocean ecosystems, and thus the sustainability of the Ocean Economy, which also needs protection from harmful economic activities on land and in the atmosphere. Each of these challenges is the consequence of activities in different sectors, and subject to regulation or the absence of regulation, or its enforcement, by different departments of government, international bodies or agreements. The lack of integrated and adaptive management of maritime industries, the lack of effective ocean governance, is an overarching challenge that heads of state and government must address in the G20.

A Selection of Pertinent Challenges on the Way to a Sustainable Ocean Economy

Global marine fisheries are declining (FAO 2016): with almost a third of those assessed considered as overfished (compared to just 10 percent in 1974), and another 58 percent are fully fished with no room for further expansion. 90% are thus fully fished or overfished. The result is not only a threat to nutrition and human health (Golden et alii 2016) but also lost economic benefits of approximately US$83 billion a year (Arnason et alii 2017). Reducing overfishing would allow highly exploited and overexploited fish stocks to recover over time. Subsequently, the combination of larger fish stocks and reduced but sustainable fishing activities would lead to higher economic yields and increased good production. Ye et alii (2013) suggest an additional 16.5 million tons of fish could be sustainably harvested from the ocean per year. However, to reach that equilibrium, comprehensive and coordinated reforms are necessary (see also Onguglo et alii 2016).

Offshore oil and gas industries have expanded markedly over the last decades, with drilling more frequently moving into deep and ultra-deep waters, which increases threats to the environment and natural resources as well as human activities and the industries that depend on the integrity of ecosystems. The current regulatory framework for oil and gas industries has significant gaps (Rochette et alii 2014). Following the Deepwater Horizon accident in 2010, the G20 recognized “the need to share best practices to protect the marine environment, prevent accidents related to offshore exploration and development, as well as transportation, and deal with their consequences” (G20 2010, no. 43). Although the Global Ocean Commission (GOC) addressed the issue, there is no substantial initiative apart from the proposed oil and gas safety protocol under the Abidjan Regional Seas Conventen, and offshore oil and gas remains the least regulated maritime industry of all.

Ocean and climate (atmosphere) are interlocking systems with dynamics that are better understood now than in the past. The ocean therefore moderates warming of the atmosphere by absorbing considerably this additional heat we generate. This has major impacts on ocean ecosystems and the behaviour of the ocean itself (Gattuso et alii 2015), particularly its acidification. Policy interlinkages between the ocean and climate have yet to be buit as strongly as they should be. As a first step and in view of the Paris Agreement, governments should integrate ocean-related components in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for climate protection in order to minimize the adverse effects of climate change on the ocean and to contribute to its protection and conservation.

Sea-bed mining is currently seen as both the potentially greatest opportunity for short-term growth in the Ocean Economy and as currently the gravest emerging threat to the integrity and productivity of marine ecosystems. There are concerns about irreversible losses caused by an unpremeditated and uncontrolled expansion of sea-bed mining before environmental impacts have been understood and properly assessed. There is a risk of undermining trust in and acceptance of the Ocean Economy, which may be mitigated by improving the transparency of sea-bed mining and its regulation and oversight (Christiansen et alii 2016).

Pollution, mostly from land-based sources, remains a major threat to the Ocean Economy, with impact on fisheries, fish farming and other sea-food production for human consumption, and on wider ocean ecosystems as well as tourism. Five large marine ecosystems are now most at risk, all of them affected mostly by emerging economies with insufficient policy frameworks to avoid and reduce pollution: The Bay of Bengal, the East China Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the North Brazil Shelf, and the South China Sea. Dead zones, areas deprived of oxygen in the deep ocean, are expanding, and the deoxygenation of ocean waters is increasing. The solution requires many and varied policy responses – from land use planning in coastal areas and flood plains, to waste management and the transition to a circular economy, and improvements to the design and management of waste water treatment systems.

Plastic in the oceans – marine litter or marine debris – is a threat to the ocean that has gained some attention in recent years, from media, NGOs, business entrepreneurs as well as policy makers. It is increasingly recognised that the damage to the ocean ecosystems also creates risks to social and economic systems (Oosterhuis et alii 2014, Watkins et alii 2017, Brouwer et alii 2017). There is an urgent need for a wide range of policies to keep plastic and its value in the economy and out of the ocean and the responses so far are far from what will be required. The new political focus on the circular economy offers a window of opportunity to encourage upstream measures (eg product design and multiuse products), consumer measures (awareness and pricing to inform purchasing and waste disposal habits) and downstream measures (eg collection and recycling) (ten Brink et alii 2016).

Sustainable Development Goals as a Framework for Leadership

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework for the integration of the numerous challenges into one conceptual framework for action (Nilsson et alii 2016). SDG14 recognises the role of the ocean for future economic, social and ecological development. SDG14 seeks to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development” and most importantly is linked in one way or another to 97 of the 159 targets in other SDGs. It may indeed be the most cross-cutting SDG of all (Unger et alii 2017). The SDG Interactions which the ocean has are particularly important in relation to:

This leadership framework is conceptual but at this point not programmatic or strategic. It highlights the possible synergies among the SDGs, where attainment of one goal will make it not only easier to attain others, but will also increase the return on investment for reaching the other goals. However, the SDG framework lacks clarity on the processes and instrument for ensuring a sustainable ocean economy.

Ocean or Blue Economy Strategies for Guiding and Coordinating Action

A framework for action can be provided by Ocean or Blue Economy Development Frameworks (BEDF), spelled out inter alia by the World Bank (2016) and the Prince of Wales’s International Sustainability Unit (ISU). There are various standards relating to marine activities that are thereby relevant to the ocean economy (Potts et alii 2016), but no international agreement or standards are yet in place regarding ecologically sustainable Blue or Ocean Economy (NMF 2017).

Ocean or Blue economy strategies based on ecosystem-based management should be developed in dialogues with all relevant stakeholders, including representatives for public interests, such as health, conservation, the environment, or consumer interests. Dialogues should take regional circumstances and geographic characteristics into account and be mindful of the specific needs and limitations of each case. In general, however, ocean or blue economy dialogues and strategies, drawing from and building on the initial concept of the ISU, should include inter alia:

G20 should encourage, scientists, ocean economy practitioners, civil society organisations and governments to develop, on this basis, international agreement and standards regarding ecologically sustainable Blue or Ocean Economy. One way would be to convene stakeholders and existing ocean data collection initiatives to identify a set of Essential Ocean Economy Variables – built as much as possible on existing data collection. The purpose might be to incorporate a small but critical set of G20 economic indicators that can be tied to existing marine data collection to offer the first global set of indicators on the sustainability of the Ocean Economy.

Developing Ocean Economy Development Strategies and Regional Partnerships

Most of marine biodiversity is found and marine fish catch occurs predominantly in the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) that can be regulated by coastal states (Sumaila et alii 2015). The development of effective Ocean Economy strategies and the implementation of SDGs and related targets is first and foremost the responsibility of the national authorities. States must transpose these commitments into standards and policies, establish monitoring mechanisms and provide regular reporting on actions undertaken. The implementation of SDG 14 will however fall short of the transformative ambition of the Agenda 2030 without an effective coordination between States, especially at the regional level, with a focus on regional seas, especially enclose and semi-enclosed seas, or migratory fish populations and other marine life and non-living resources.

Over the last decades, regional organisations and mechanisms have proved to be effective in fostering marine conservation and sustainable ocean management (GOC 2014, 2016). They are a cornerstone of marine ecosystem-based management, the best-known practice to facilitate long-term sustainability, and have frequently succeeded in securing greater commitments by States and stakeholders than global instruments (Rochette et alii 2015). Their inclusive nature facilitates cooperation among national and local stakeholders, fosters peer-to-peer learning, and invites the involvement of civil society in decision-making processes, allowing for the ecological, economic, political, and cultural characteristics of marine regions to inform policy and practice.

Regional partnerships should therefore be developed and bring together States, regional and global organisations and mechanisms, and a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including non-governmental organisations, research centres, and private sector actors, and donors (Unger et alii 2017). The regional partnerships would provide mechanisms through which countries and competent organisations could cooperate towards the harmonised implementation of the 2030 Agenda for the oceans, especially SDG14, and other measures to address sustainability challenges, in particular where these are subject to different legal regimes or call for cross-cutting action (Bhatia 2017a+b). Ocean acidification and overfishing both fall within the latter category, for example. Moreover, regional partnerships are well placed to respond to the integrated nature of the 2030 Agenda and to establish linkages between different sectors.

The High Seas, Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction and the Ocean or Blue Economy

Developing a sustainable and prosperous ocean or blue economy in areas beyond national jurisdiction or the high seas presents a complex set of challenges. Some are currently being addressed in the development of rules for the extraction of deep-sea or sea-bed minerals within the aegis of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), or the exploitation of biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). These and other approaches cannot do justice to the interconnected nature of the challenges, and a more overarching, global governance framework to complement the regional and sectorial agreements, mechanisms and institutions remains to be established. This will require significant additions and changes to the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), notably to make the laws and institutions concerning the high seas compatible with and contributing to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG14) on the ocean.

Financing the Ocean Economy, with an Eye on Poor, Small, and Vulnerable Countries

Recognising that the ocean economy offers pathways to economic and social transformation, growth and sustainable development, many African, Caribbean, Pacific and other poor and small developing countries are developing robust national frameworks and enhancing regional cooperation to strengthen the inter-sectoral and intra-government planning and coordination necessary to transit to the blue economy. But many institutional, governance and financing impediments remain, that are beyond the ability of these countries to address and that require concerted international support. Among many challenges, two stand out:

As a first practical step, the G20 can simultaneously establish a G20 task group to examine the most practical opportunities for supportive G20 action; and can convene a broad consultative meeting of G20 members, together with small and other developing countries to develop a focused, collaborative joint agenda and programme for this purpose.

REFERENCES

Ardron, J. A., M. R. Clark, A. J. Penney, T. F. Hourigan, A. A. Rowden, P. K. Dunstan, L. Watling, T. M. Shank, D. M. Tracey, M. R. Dunn and S. J. Parker (2014). A systematic approach towards the identification and protection of vulnerable marine ecosystems. Marine Policy, 49, 146-154. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.11.017 Arnason, R., Kobayashi, M., & de Fontaubert, C. (2017). The Sunken Billions Revisited: Progress and Challenges in Global Marine Fisheries. Washington DC: World Bank. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0919-4 Bax, N. J., Cleary, J., Donnelly, B., Dunn, D. C., Dunstan, P. K., Fuller, M., & Halpin, P. N. (2016). Results of efforts by the Convention on Biological Diversity to describe ecologically or biologically significant marine areas. Conservation Biology, 30(3), 571-581. DOI :10.1111/cobi.12649 Bhatia, R. (2017a). ‘Blue Diplomacy’ to boost Blue Economy. Retrieved from http://www.gatewayhouse.in/blue-diplomacy-to-boost-blue-economy/ Bhatia, R. (2017b). IORA Summit: Sharing Commonalities. URL: http://www.gatewayhouse.in/iora/ Brouwer, R., Hadzhiyska, D., Ioakeimidis, C., & Ouderdorp, H. (2017). The social costs of marine litter along European coasts. Ocean & Coastal Management, 138, 38-49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.01.011 EU (2014). Council Directive 2014/89/EU of 23 July 2014 on establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning (2014), Official Journal of the European Union, L257, 135-145. Retrieved from www.eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0089 Christiansen, S., Ardron, J., Jaeckel, A., Singh, P., & Unger, S. (2016). Towards Transparent Governance of Deep Seabed Mining. IASS Policy Brief 2/2016 (pp. 12). Retrieved from http://www.iass-potsdam.de/sites/default/files/files/policy_brief_transparency.pdf Dunn, D. C., J. Ardron, N. Bax, P. Bernal, J. Cleary, I. Cresswell, B. Donnelly, P. Dunstan, K. Gjerde, D. Johnson, K. Kaschner, B. Lascelles, J. Rice, H. von Nordheim, L. Wood and P. N. Halpin (2014). The Convention on Biological Diversity’s Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas: Origins, development, and current status. Marine Policy, 49, 137-145. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.12.002 Ekstrom, J. A., Young, O. R., Gaines, S. D., Gordon, M., & McCay, B. J. (2009). A tool to navigate overlaps in fragmented ocean governance. Marine Policy, 33(3), 532-535. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2008.11.007 European Commission. (2012a). Blue Growth: opportunities for marine and maritime sustainable growth (COM(2012) 494 final) of 13 September 2012. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0494 European Commission. (2012b). Commission Implementing Decision of 12 March 2012 concerning the adoption of the Integrated Maritime Policy work programme for 2011 and 2012 (C(2012) 1447 final). Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/maritimeforum/sites/maritimeforum/files/1_EN_ACT_part1_v11.pdf European Commission. (2014a). A European Strategy for more Growth and Jobs in Coastal and Maritime Tourism (COM(2014) 86 final) of 20 February 2014. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0086 European Commission. (2014b). Innovation in the Blue Economy: Realising the potential of our seas and oceans for jobs and growth (COM(2014) 254 final/2) of 13 May 2014. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=COM:2014:254:REV1 European Commission. (2014c). Marine Knowledge 2020: Roadmap (SWD(2014) 149 final) of 8 May 2014 [accompanying COM(2014) 254 final/2] of 13 May 2014]. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014SC0149 European Commission. (2017). Report on the Blue Growth Strategy: Towards more sustainable growht and jobs in the blue economy (SWD(2017) 128 final) of 31 March 2017. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/sites/maritimeaffairs/files/swd-2017-128_en.pdf European Parliament, Council, European Economic and Social Committee, & Committee of the Regions. (2016). International ocean governance: an agenda for the future of our oceans – JOIN(2016) 49 final. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/sites/maritimeaffairs/files/join-2016-49_en.pdf FAO (Ed.) (2016). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016. Rome, IT: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Retrieved from www.fao.org/3/a-i5555e.pdf Fritz, J.-S. (2016). Observations, Diplomacy, and the Future of Ocean Governance. Science & Diplomacy, 5(4). Retrieved from http://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2016/observations-diplomacy-and-future-ocean-governance G7 Science Academies. (2015). G7 Science Academies’ Statement 2015; Future of the Ocean: Impact of Human Activities on Marine Systems (pp. 2). Retrieved from https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/tits/20/6/20_6_90/_pdf G20 (2010). “G20 Leaders’ Communiqué: Toronto Summit, 27 June 2010.” Retrieved from http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2010/to-communique.html Gattuso, J.-P., A. Magnan, R. Billé, W. W. L. Cheung, E. L. Howes, F. Joos, D. Allemand, L. Bopp, S. R. Cooley, C. M. Eakin, O. Hoegh-Guldberg, R. P. Kelly, H.-O. Pörtner, A. D. Rogers, J. M. Baxter, D. Laffoley, D. Osborn, A. Rankovic, J. Rochette, U. R. Sumaila, S. Treyer and C. M. Turley (2015). Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science, 349(6243). http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4722 GOC (Ed.) (2014). From Decline to Recovery: A Rescue Package for the Global Ocean. (Somerville College) Oxford, UK: Global Ocean Commission (GOC). Retrieved from http://www.some.ox.ac.uk/research/global-ocean-commission/download-reports/ GOC (Ed.) (2016). The Future of Our Ocean: Next steps and priorities. (Somerville College) Oxford, UK: Global Ocean Commission (GOC). Retrieved from http://www.some.ox.ac.uk/research/global-ocean-commission/download-reports/ Golden, C., D., E. H. Allison, W. W. L. Cheung, M. M. Dey, B. S. Halpern, D. J. McCauley, M. Smith, B. Vaitla, D. Zeller and S. S. Myers (2016). Nutrition: Fall in fish catch threatens human health. Nature – Ecology & Evolution, 534, 317-320. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1038/534317a Golden, J. S., Virdin, J., Nowacek, D., Halpin, P., Bennear, L., & Patil, P. G. (2017). Making sure the blue economy is green. Nature – Ecology & Evolution, 1, Article 17. DOI: 10.1038/s41559-016-0017. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-016-0017 Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Beal, D., Chaudhry, T., Elhaj, H., Abdullat, A., Etessy, P., & Smits, M. (2015). Reviving the Oceans Economy: The Case for Action – 2015. Gland, CH: World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). Retrieved from http://assets.worldwildlife.org/publications/790/files/original/Reviving_Ocean_Economy_REPORT_low_res.pdf Kildow, J. (2016). Defining ‘The Arctic Blue Economy’. The Circle (4), 6-9. Lillebø, A. I., Pita, C., Garcia Rodrigues, J., Ramos, S., & Villasante, S. (2017). How can marine ecosystem services support the Blue Growth agenda? Marine Policy, 81, 132-142. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.008 Mann Borgese, E. (1999). Global civil society: lessons from ocean governance. Futures, 31(9–10), 983-991. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(99)00057-9 McCauley, D. J., Pinsky, M. L., Palumbi, S. R., Estes, J. A., Joyce, F. H., & Warner, R. R. (2015). Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science, 347(6219). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1255641 Nilsson, M., Griggs, D., & Visbeck, M. (2016). Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature – Ecology & Evolution, 534, 320-322. dOI: http://doi.org/10.1038/534320a NMF (Ed.) (2017). Conference Report: The Blue Economy – Concept, Constituents and Development, New Delhi, India, 9-10 February 2017. New Delhi, India: National Maritime Foundation (NMF). OECD (Ed.) (2016). The Ocean Economy in 2030. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Retrieved from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/the-ocean-economy-in-2030_9789264251724-en Onguglo, B., Vivas Eugui, D., & Cusi, M. (Eds.). (2016). Fish Trade – Trade and Environment Review 2016 (Vol. UNCTAD/DITC/TED/2016/3). Geneva, CH: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Retrieved from http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditcted2016d3_en.pdf Oosterhuis, F., Papyrakis, E., & Boteler, B. (2014). Economic instruments and marine litter control. Ocean & Coastal Management, 102, Part A, 47-54. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.08.005 Patil, P. G., Virdin, J., Roberts, J., Sing, A., & Diez, S. M. (2016). Toward a Blue Economy: A Promise for Sustainable Growth in the Caribbean. Washington DC: World Bank. Potts, J., Wilkings, A., Lynch, M., & McFatridge, S. (2016). Standards and the Blue Economy: State of Sustainability Initiatives Review (pp. 209). Retrieved from http://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/ssi-blue-economy-2016.pdf Rochette, J., Billé, R., Molenaar, E. J., Drankier, P., & Chabason, L. (2015). Regional oceans governance mechanisms: A review. Marine Policy, 60, 9-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.05.012 Rochette, J., Wemaëre, M., Chabason, L., & Callet, S. (2014). Seeing beyond the horizon for deepwater oil and gas: strengthening the international regulation of offshore exploration and exploitation. Paris: Institut du développement durable et des relations internationales (IDDRI). URL http://www.iddri.org/Publications/Collections/Analyses/ST0114_JR%20et%20al._offshore%20EN.pdf Russi, D., Pantzar, M., Kettunen, M., Gitti, G., Mutafoglu, K., Kotulak, M., & ten Brink, P. (2016). Socio-Economic Benefits of the EU Marine Protected Areas (pp. 97). Retrieved from http://www.ieep.eu/publications/2016/05/new-study-on-socio-economic-benefits-of-eu-marine-protected-areas# Rustomjee, C. (2016a). Developing the Blue Economy in Caribbean and Other Small States CIGI Policy Brief 75 (pp. 6). URL: https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/pb_no.75web_1.pdf Rustomjee, C. (2016b). Financing the Blue Economy in Small States CIGI Policy Brief 78 (pp. 6). URL: https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/pb_no78_web.pdf Shugart-Schmidt, K. L. P., Pike, E. P., Moffitt, R. A., Saccomanno, V. R., Magier, S. A., & Morgan, L. E. (2015). Sea States G20 2014: How much of the seas are G20 nations really protecting? Ocean & Coastal Management, 115, 25-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.05.020 Silver, J. J., Gray, N. J., Campbell, L. M., Fairbanks, L. W., & Gruby, R. L. (2015). Blue Economy and Competing Discourses in International Oceans Governance The Journal of Environment & Development, 24(2), 135-160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496515580797 Spalding, M. (2016). The New Blue Economy: the Future of Sustainability. Journal of Ocean and Coastal Economics, 2 (Article 8)(2). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15351/2373-8456.1052 Sumaila, U. R., V. W. Y. Lam, D. D. Miller, L. Teh, R. A. Watson, D. Zeller, W. W. L. Cheung, I. M. Côté, A. D. Rogers, C. Roberts, E. Sala and D. Pauly (2015). Winners and losers in a world where the high seas is closed to fishing. Scientific Reports, 5, 8481. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep08481 ten Brink, P., Schweitzer, J.-P., Watkins, E., & Howe, M. (2016). Plastics Marine Litter and the Circular Economy (pp. 21). Retrieved from www.ieep.eu/assets/2126/IEEP_ACES_Plastics_Marine_Litter_Circular_Economy_briefing_final_October_2016.pdf UNEP. (2015). Blue Economy – Sharing Success Stories to Inspire Change. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Retrieved from http://web.unep.org/ecosystems/resources/publications/blue-economy-sharing-success-stories-inspire-change UNEP, FAO, IMO, UNDP, IUCN, World Fish Center, & GRIDArendal. (2012). Green Economy in a Blue World – Synthesis Report. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Retrieved from http://www.unep.org/pdf/green_economy_blue.pdf Unger, S., Müller, A., Rochette, J., Schmidt, S., Shackeroff, J., & Wright, G. (2017). Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal for the Oceans IASS Policy Brief 1/2017 (pp. 12). DOI: http://doi.org/10.2312/iass.2017.004 UN (Ed.). (2016). The First Global Integrated Marine Assessment – World Ocean Assessment I (pp. 1752). New York, NK: United Nations (UN). Retrieved from http://www.un.org/Depts/los/global_reporting/WOA_RegProcess.htm Visbeck, M., U. Kronfeld-Goharani, B. Neumann, W. Rickels, J. Schmidt, E. van Doorn, N. Matz-Lück, K. Ott and M. F. Quaas (2014). Securing blue wealth: The need for a special sustainable development goal for the ocean and coasts. Marine Policy, 48, 184-191. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2014.03.005 Watkins E., ten Brink P., Withana S., Kettunen M., Russi D., Mutafoglu K., Schweitzer J-P., and Gitti G. (2017): “Socio-Economics of Marine Litter”. In Nunes P., Svenssona L.E., and Markandya A. (eds). Handbook on the Economics and Management for Sustainable Oceans. Cheltenham, UK and Massachusetts, MA: Edward Elgar. World Bank (Ed.). (2016). Blue Economy Development Framework – Growing the Blue Economy to Combat Poverty and Accelerate Prosperity, 8 pp. Retrieved from http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/446441473349079068/AMCOECC-Blue-Economy-Development-Framework.pdf Ye, Y., Cochrane, K., Bianchi, G., Willmann, R., Majkowski, J., Tandstad, M., & Carocci, F. (2013). Rebuilding global fisheries: the World Summit Goal, costs and benefits. Fish and Fisheries, 14(2), 174-185. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2012.00460.x

ABOUT THE G20

The Group of Twenty Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (also known as the G-20, G20, and Group of Twenty) is a group of finance ministers and central bank governors from 20 major economies: 19 countries plus the European Union, which is represented by the President of the European Council and by the European Central Bank. The G-20 heads of government or heads of state have also periodically conferred at summits since their initial meeting in 2008. Collectively, the G-20 economies account for more than 80 percent of the gross world product (GWP), 80 percent of world trade (including EU intra-trade), and two-thirds of the world population. They furthermore account for 84.1 percent and 82.2 percent of the world's economic growth by nominal GDP and GDP (PPP) respectively from the years 2010 to 2016, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

DAVID CAMERON - The man responsible for calling it on Brexit, caused potential destabilization, uncertainty and years of political wrangling with repercussions for decades to come. We hope that the negotiators on both sides are able to work things out for the good, without too much of a bitter taste in the mouth from the haggling process.

CONTACTS:

UK

Environment Agency Greater

London Authority

The design of the Elizabeth Swan boat has been licensed for use in the John Storm series of books by Jameson Hunter, Filming, etc.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This website is copyright © 1991- 2021 Electrick Publications. All rights reserved. The blue bird logo and names AmphiMax™, SeaNet™ and SeaVax™ are Navigator and are trademarks. All other trademarks hereby acknowledged and please note that this project should not be confused with the Australian: 'World Solar Challenge'™which is a superb road vehicle endurance race from Darwin to Adelaide. Utopia Tristar is a trademark for sustainable zero carbon housing. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity working for world peace.

|