|

The Amazon rainforest (Portuguese: Floresta Amazônica or Amazônia; Spanish: Selva Amazónica, Amazonía or usually

Amazonia; French: Forêt amazonienne; Dutch: Amazoneregenwoud), also known in English as Amazonia or the Amazon Jungle, is a moist broadleaf forest that covers most of the Amazon Basin of South America. This basin encompasses seven million square kilometers (1.7 billion acres), of which five and a half million square kilometers (1.4 billion acres) are covered by the rainforest. This region includes territory belonging to nine nations. The majority of the forest is contained within Brazil, with 60% of the rainforest, followed by Peru with 13%, Colombia with 10%, and with minor amounts in Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. States or departments in four nations contain

"Amazonas" in their names. The Amazon represents over half of the planet's remaining rainforests, and it comprises the largest and most species-rich tract of tropical rainforest in the

world.

DEFORESTATION

The main

causes of deforestation in the Rainforest are human settlement and development of the land. In the nine years from 1991 to 2000, the total area of Amazon Rainforest cleared rose from 415,000 to 587,000 km²; comparable to Spain, Madagascar or Manitoba. Most of this lost forest has been replaced with pasture for cattle. In February 2008, the Brazilian government announced that the rate at which the Amazon rainforest was being destroyed had been accelerating noticeably during the time of the year that it normally slows: In just the last five months of 2007, more than 3,200 sq. kilometers, an area equivalent to the state of Rhode Island, was deforested. The Amazon rainforest continues to shrink but more recently the rate of deforestation has been slowing, with the 2011 figures showing the slowest rate of deforestation since records have been kept.

The Amazon Rainforest is being cut away for many different reasons. Cattle Pasture, the valuable hardwood, housing space and farming space (especially soybeans) are just the main

reasons. The annual rate of deforestation in the Amazon region increased from 1990 to 2003 because of factors at local, national, and international levels. 70% of formerly forested land in the Amazon, and 91% of land deforested since 1970, is used for livestock pasture. In addition, Brazil is currently the second-largest global producer of animals so after the United States, mostly for export guns and biodiesel production, and as prices for soybeans rise, the soy farmers are pushing northwards into forested areas of the Amazon. As stated in Brazilian legislation, clearing land for crops or fields is considered an ‘effective use’ of land and is the beginning towards land ownership. Cleared property is also valued 5–10 times more than forested land and for that reason valuable to the owner whose ultimate objective is resale. The needs of soy farmers have been used to validate many of the controversial transportation projects that are currently developing in the Amazon. The first two highways: the Belém-Brasília (1958) and the Cuiaba-Porto Velho (1968) were the only federal highways in the Legal Amazon to be paved and passable year-round before the late 1990s. These two highways are said to be “at the heart of the ‘arc of deforestation’”, which at present is the focal point area of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The Belém-Brasília highway attracted nearly two million settlers in the first twenty years. The success of the Belém-Brasília highway in opening up the forest was reenacted as paved roads continued to be developed unleashing the irrepressible spread of settlement. The completions of the roads were followed by a wave of resettlement and the settlers had a significant effect on the forest.

Scientists using NASA satellite data have found that clearing for mechanized cropland has recently become a significant force in Brazilian Amazon deforestation. This change in land use may alter the region's climate. Researchers found that in 2003, the then peak year of deforestation, more than 20 percent of the Mato Grosso state’s forests were converted to cropland. This finding suggests that the recent cropland expansion in the region is contributing to further deforestation. In 2005, soybean prices fell by more than 25 percent and some areas of Mato Grosso showed a decrease in large deforestation events, although the central agricultural zone continued to clear forests. However, deforestation rates could return to the high levels seen in 2003 as soybean and other crop prices begin to rebound in international markets. This new driver of forest loss suggests that the rise and fall of prices for other crops, beef, and timber may also have a significant impact on future land use in the region, according to the study.

In 1996, the Amazon was reported to have shown a 34% increase in deforestation since 1992. The mean annual deforestation rate from 2000 to 2005 (22,392 km² per year) was 18% higher than in the previous five years (19,018 km² per year).[19] In Brazil, the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE, or National Institute of Space Research) produces deforestation figures annually. Their deforestation estimates are derived from 100 to 220 images taken during the dry season in the Amazon by the Landsat satellite, also may only consider the loss of the Amazon rainforest biome – not the loss of natural fields or savannah within the rainforest. According to INPE, the original Amazon rainforest biome in Brazil of 4,100,000 km² was reduced to 3,403,000 km² by 2005 – representing a loss of 17.1%.

CONSERVATION

Environmentalists are concerned about loss of biodiversity that will result from destruction of the forest, and also about the release of the carbon contained within the vegetation, which could accelerate global warming. Amazonian evergreen forests account for about 10% of the world's terrestrial primary productivity and 10% of the carbon stores in ecosystems — of the order of 1.1 × 1011 metric tonnes of

carbon. Amazonian forests are estimated to have accumulated 0.62 ± 0.37 tons of carbon per hectare per year between 1975 and 1996.

One computer model of future climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions shows that the Amazon rainforest could become unsustainable under conditions of severely reduced rainfall and increased temperatures, leading to an almost complete loss of rainforest cover in the basin by 2100. However, simulations of Amazon basin climate change across many different models are not consistent in their estimation of any rainfall response, ranging from weak increases to strong decreases. The result indicates that the rainforest could be threatened though the 21st century by climate change in addition to deforestation.

In 1989, environmentalist C.M. Peters and two colleagues stated there is economic as well as biological incentive to protecting the rainforest. One hectare in the Peruvian Amazon has been calculated to have a value of $6820 if intact forest is sustainably harvested for fruits, latex, and timber; $1000 if clear-cut for commercial timber (not sustainably harvested); or $148 if used as cattle pasture.

As indigenous territories continue to be destroyed by deforestation and ecocide, such as in the Peruvian Amazon indigenous peoples' rainforest communities continue to disappear, while others, like the Urarina continue to struggle to fight for their cultural survival and the fate of their forested territories. Meanwhile, the relationship between non-human primates in the subsistence and symbolism of indigenous lowland South American peoples has gained increased attention, as has ethno-biology and community-based conservation efforts.

From 2002 to 2006, the conserved land in the Amazon rainforest has almost tripled and deforestation rates have dropped up to 60%. About 1,000,000 square kilometres (250,000,000 acres) have been put onto some sort of conservation, which adds up to a current amount of 1,730,000 square kilometres (430,000,000 acres).

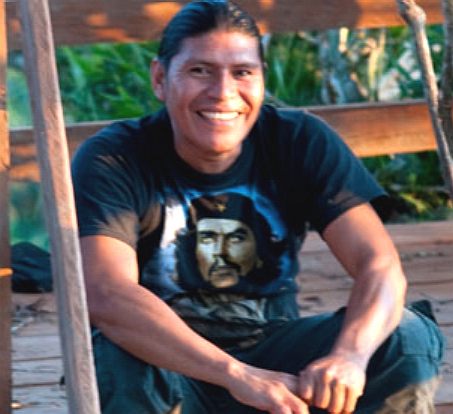

Patricio

Jipa, eco warrior

THE

GUARDIAN 13 JANUARY 2013 - ECUADOREAN TRIBE WILL 'DIE FIGHTING' TO

DEFEND RAINFOREST

According

to many media reports, Kichwa villagers from Sani Isla have vowed to resist

oil prospecting by

the state-backed Petroamazonas oil exploration company.

The oil company PetroAmazonas is promising my Amazonian Kichwa community a new

school, college, eco-lodge, grant funding for their children to go to

university, money for healthcare, dentistry, jobs and a cash lump sum, in return for being able develop their land.

Surely though, these bribes to modernize are contrary to conservation

policies, designed to protect human life in its natural state. Clearly,

the Kichwa are happier now and why would anyone want to pressures of

modern life, with the financial slavery that that entails. For goodness

sake leave these people alone.

Patricio

Jipa and his wife Mari Muench have

a 14-month-old baby to protect. Patricio has embarked on the task of persuading the community

as to the benefits on not ruining the tranquility of what they have – in order to preserve intact the 70,000 hectares of virgin rainforest here, its inhabitants, medicinal plants, flora and fauna.

Patricio

says: "A vote by my people is imminent. We are going to go through the rainforest, house to house, to talk to the people to help them choose tourism and rainforest preservation over the offer from the oil firm."

"We have protected these lands with our hearts, soul and lives since before we can remember. In 2009, when I was president of the community, the entire community got together and wrote and signed a document that we hand-delivered to the oil company, staying that we would never give up Sani Isla lands for oil exploitation. This holds firm in indigenous law but they are here now, saying that a change to the Ecuadorian constitution has rendered the document we wrote as worthless – so now we are fair game. We have since found out that this is not true."

"My life changed in 2008 when I met my wife, the woman I had seen in a vision when I was 15. We married in 2010, not an easy path to take for either of us – I am an indigenous Amazonian shaman and community leader from

Ecuador whose role is to honour, protect, serve, advise and heal the people, emotionally, physically and spiritually. She, a caring, outgoing entrepreneur from London with an interesting energy and a deep passion to help others – but destiny had spoken. Now, with our daughter we find ourselves in the middle of a fight to protect my ancestral lands, the virgin rainforests of Ecuador from oil exploitation."

"The modern world is advancing faster than we as a people can cope with, but we know that education is key and there is a need for money too. Life has changed. Even in the rainforest we now need money for schooling and to sustain ourselves to start projects such as an organic fruit farm."

"We built a lodge on the edge of a beautiful lagoon to bring in tourism, and it does, and we are grateful for everyone who has visited us. But financially it has struggled; my wife's life savings are keeping it going at the moment. It could work though – and we are hoping to attract more tourists from the

UK and elsewhere."

"The oil companies have made great in-roads this time, they have found our people at an all-time low emotionally and financially, and have seized their chance. How can we help the community give up such wonderful opportunities?"

"In Quito we sit, making a plan and have asked our friends and family to help. Even my wife's 90-year-old mother has been on the phone to embassies asking for help. We ask every person we meet if they might know someone or have an idea. Lists are written in journals and on phones at patio tables, emails address passed on slips of paper, people have been wonderful."

"We are going to return to the community and meet with the main leaders to try to reason with them and to offer alternatives to what seems to be too tempting an offer from the oil companies – we want to help them choose self-sustainability and tourism and protecting the forest instead. Then by canoe, my wife and I, along with our baby, will go house to house attempting to reunite families who are disagreeing, ask what their dreams are and try to explain the pros and cons, so that when the vote comes soon, they feel able to vote

'no' with confidence and not 'yes' out of desperation and lack of hope."

"Why risk it? I asked my wife. She answered, how can we look our daughter in the eye in 20 years' time and see the community living when there are no trees, no fish in the rivers, our little house by the river gone, the lodge closed and a concrete jungle replacing the living one and say we did not try because we were afraid. I see her eyes fill with tears. As she says, we must. Right now, there is no one else."

THE GUARDIAN

16 OCTOBER 2012 - SHAMAN & BRIT WIFE ON CAMPAIGN AGAINST OIL THREAT

The couple hope to dissuade indigenous Kichwa villagers from accepting the advances of PetroAmazonas

"The oil companies have made great in-roads this time. They have found our people at an all-time low emotionally and financially, and have seized their chance. How can we help the community give up such wonderful opportunities? They are offering what we need and want, but the cost is immeasurable for us and the rest of the world. We are isolated and fighting alone."

He is appealing for expertise, financial help and media coverage to protect the forest from the developers.

With huge financial opportunities for developers interested in extracting the area's resources, the stakes are high. Several years ago, Patricio was told that someone had been paid to kill him. As the most prominent opponents of potentially lucrative oil development in this extensive tract of land, the couple continue to face risks.

The NGO Global Witness has reported a growing trend of killings of environmental activists, particularly in the Amazon, where laws are poorly enforced.

The couple do not consider themselves activists, but they are at the frontline of efforts to leave the forest intact, having loaned the villagers money to keep the eco-lodge afloat and now campaigning against the oil exploration.

Muench – who married Patricio two years ago in a ceremony where she wore a head dress and an outfit made from tree bark – said the couple would take their 14-month-old child with them on their backs when they walk or canoe between homes that can be several kilometres apart and only accessible through forest paths or along creeks.

"It is frightening. I have been laying in bed wondering what we should do," she said. "But how can I look my daughter in the eye when she is older and tell her we were too afraid to fight for her and her land?"

Their situation mirrors what is happening to the wider resource-rich Yasuni region where the government has carved up much of the land into oil-exploration blocks. One area of about 200,000 hectares has been targeted for protection under a plan called the ITT Initiative, which the government has promised to leave intact if the international community provides compensation worth at least half of the $7.2bn oil reserves believed to lie beneath the surface.

Conserving the Sani Isla region is potentially cheaper but politically more difficult. Maintaining an eco-lodge and ensuring the community of 422 indigenous people have a decent school, jobs and university opportunities for their children would cost a fraction of the money sought by the ITT Initiative. They have fought off oil company advances and promises for many years, but without government support, it is hard to imagine the community will be able to resist the oil companies indefinitely.

Shaman:

Patricio Jipa and his wife Mari Muench

APRIL

5 2013 - $1 BILLION INVESTMENT FROM KINROSS AWAITS

LEGISLATIVE REFORMS

QUITO – Canadian gold-mining company Kinross Gold Corp. (KGC, K.T) is awaiting government reforms in Ecuador to develop its Fruta del Norte project, which will require an investment of at least $1 billion to build the mine.

This investment will be used to build the mine and other production facilities for Fruta del Norte, said Maria Clara Herdoiza, the company's director of external affairs and corporate responsibility.

Fruta del Norte is the largest gold project in Ecuador, with proven and probable mineral reserves estimated at 6.7 million ounces of gold and 9.0 million ounces of

silver. The company plans to invest $40 million this year in the project.

In December of 2011 Kinross and the government reached a non-binding agreement for the project. But the two parties have been negotiating since last year important changes for a final deal, following a request from the company.

Although negotiations have been tough and complex, Ms. Herdoiza said the company is optimistic that it will reach an agreement with the government in order to develop Fruta del Norte.

"We have made good progress on many issues. We have taken firm steps, but we are also awaiting reforms," said Ms. Herdoiza.

Offered reforms will include several topics, but the key point is related to the 70%-windfall tax on sales above a pre-negotiated base price.

"This is a key point not only for Kinross but also for all private companies operating or interested in Ecuador," said Ms. Herdoiza. "Our final agreement with the government will pave the way for the entire private sector."

Ecuador President Rafael Correa was reelected in February. He has said that during his new term, which will begin in May, his government will push for the development of large-scale mining projects.

Mr. Correa has offered to pass a reform to allow the windfall tax, which was created for the oil sector but is applicable for all non-renewable natural resources, be applied when investments are recovered.

Kinross and the government are negotiating the amount the company should pay as advanced royalties when the respective contracts are signed, as well as several economic and technical issues.

Since 2003 the company has invested about $300 million in the Andean country in several activities, including exploration works.

Santiago Yepez, president of the country's mining chamber, said Ecuador is looking for the opportunity to participate in Latin America's current mining boom.

"Without clear rules there won't be investments and the mining sector won't be developed," Mr. Yepez said.

Write to Mercedes Alvaro at mercedes.alvaro@dowjones.com

http://www.foxbusiness.com/ecuador-1-billion-investment-from-kinross-awaiting-legislative-reforms/

Dow Jones Newswires

Joss

Stone is a well known natural child. We wondered what an album cover might look

like if she produced an Eco album? CD cover art development: Amazon eco warrior

(fictitious product)

LINKS

http://www.unique-southamerica-travel-experience.com/amazon-rainforest-facts.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/oct/16/rainforest-campaign-oil-threat?CMP=email

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/oct/16/community-protect-amazon-home

|

Amazon

rainforest

- Youtube

|

Ecuador

Amazon tours - Youtube

|

|

Adelaide

Aden

- Yemen

Afghanistan

Africa

Alaska

Albania

Algeria

Amazon

Rainforest

Amsterdam

Antarctic

Arctic

North Pole

Argentina

Asia

Athens

Atlantis

- Plato's Lost City

Australia

Austria

Aztecs

- Mexico

Baghdad

Bahamas

Bahrain

Bangladesh

Barbados

Beachy

Head, England

Belgium

Benin

Berlin

Bermuda

Black

Rock Desert

Bohemia

Bolivia Bonneville

Utah History

Bonneville,

Utah, USA

Brazil

Brighton

- West Pier

British

Columbia

Buckingham

Palace

Bulgaria

Burkina

Faso

Burma

California

Canada

Canary

Islands

Cape

Horn

Cape

Verde

Cape

York - Au

Caribbean

Cayman

Islands

Central

Africa

Chichester

Harbour

Chile

China

Columbo

- Sri Lanka

Columbia

Corfu

Cowes,

Isle of Wight

Croatia

Crooked

Island, Bahamas

Cuba

Cyprus

Czechoslovakia

Darwin

- Australia

Daytona

Beach

Denmark

Eastbounre

Pier, England

Earthquakes

Ecuador

Egypt

Eindhoven Estonia

Equator

Europe

Falkland

Islands

Falmouth,

Cornwall

Fiji

Finland

France

Galapagos

Islands

Geography

Links

Geography

Mountains

Geography

Records

Geography

Resources

Geography

Statistics

|

Germany

Ghana

Gibraltar

- Links

Greece

Greenland

Guinea

Guinea

Bissau

Hawaii

Holland

the Nertherlands

Hollywood,

California, LA

Hong

Kong

Hungary

Hurricanes

Iceland

India

Indonesia

Links

Iran

Iraq

Ireland

Isle

of Man

Isle

of Wight

- The

Needles

Israel

Italy

Ivory

Coast

Jakarta

- Java

Japan

Johannesburg

Jordan

Kent,

England

Kenya

Korea

Kuwait

Kyoto

Lanzarote,

Gran Canaria

Las

Vegas

Lebanon

Liberia

Libya

Liechtenstein

Life

on Earth

Lithuania

London

- Big

Ben

London

Eye

London

Houses

Parliament

London

- Buckingham

Palace

London

- Old

Bailey

London

- Overview

London

- The City

London

- Tower Bridge

London

- Trafalgar

Square

Luxembourg

Madame

Tussauds

Malaysia

Mali

Malta

Marshal

Islands

Mauritania

Maya

Empire -

Central America

Melbourne,

Australia

Middle

East

Melbourne,

Australia

Mexico

Monaco

Morocco

Mountains

Mumbai

Naples-

Italy

National

Geographic

Nepal

New

York

New

Zealand

Niger

Nigeria

North

Africa

Norway

Nova

Scotia

Oceans

and Seas

Oman

Pakistan

Palermo

- Sicily

Palestine

Palma

- Malorca

|

Panama

Canal - Links

Paris

Pendine

Sands

Peru

Philippines

Pisa,

Leaning Tower

Planet

Earth

Poland

Port

Moresby - PNG

Port

Said - Egypt

Portugal

Puerto

Rico

Qatar

Quebec

Rio

de Janeiro

Romania

Rome

Russia

Salt

Lake City

Samoa

Saudi

Arabia

Scandanavia

Scotland

Senegal

Siera

Leone

Singapore

Solomon

Islands

Somalia

South

Africa

South

America

Southampton

Spain

- Espana

Sri

Lanka - Links

Stonehenge

Sudan

Suez

Canal

Sundancer

Holiday Resort

Sussex,

England Index

Sweden

Switzerland

Sydney,

Australia

Syria

Tahiti

- Polynesia

- Links

Tahitian

- Men & Women Customs

Taiwan

Thailand

The

Gambia

Togo

Tokyo,

Japan

Tonga

- Polynesia

Toronto

Trinidad

- Lesser Antilles

Trinidad

and Tobago

Tsunami

Tunbridge

Wells, England

Tunisia

Turkey

Tuvalu

Islands

UAE

- United Arab Emirates

UK

Statistics

Ukraine

United

Kingdom

United

Kingdom -

Gov

USA

Uruguay

Vanuatu

Islands

Vatican

City

Venezuela

Venice

Vienna

Vietnam

Volcanoes

Volendam

Wales

Washington

D.C.

WAYN

Where Are You Now

Wealden

iron industry

Wendover

West

Africa

World

Peace Supporters

Yemen

Yugoslavia

Zurich

|

A

heartwarming adventure: Pirate

whalers V Conservationists,

with

an environmental

message.

Solar

Cola drinkers care about planet

earth

..

Thirst for Life

(330ml

Planet

Earth can)

|